My Mom Died Last Year, And This Is What I've Learned Since Then

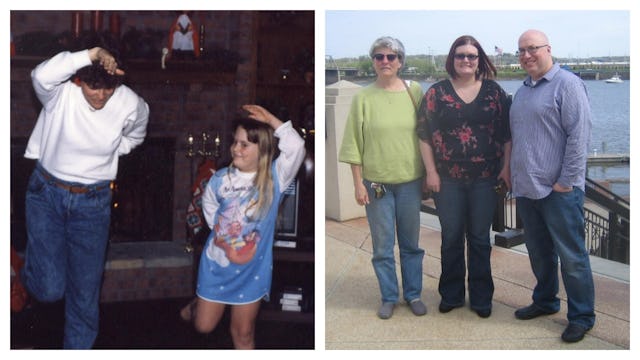

My mom lost her battle with leukemia just over a year ago. Now, as in then, it seems surreal that 35 years is all I’ll get with her.

We canceled a weekend trip, literally requesting our bag off the plane, to help my dad call family members and take her home on hospice care. We promised her we wouldn’t let my dad get too worn-out caring for her in her final days, and all her children spent her last week with her at the farm she loved and made a home.

This past year without her hasn’t been easy, but I’ve learned some lessons I probably wouldn’t have learned any other way:

1. I have more choices than I thought.

I’m a very goal-oriented person. I like setting targets and feel anxious or nervous when I’m not seeing incremental progress toward those goals. I like being in environments where others have visions and goals too.

As my grief eased, I saw that too much of my life, my emotional headspace, was about work, and when I looked at the major professional goals I had, I wasn’t making enough progress toward them at my job. I had once loved the field I was in, but I was stressed. I was rarely happy.

I feared leaving would limit my opportunities, but it didn’t. I found one new opportunity, and it opened a floodgate of new experiences and possibilities. My personal finances would have supported moving, taking a pay cut, or going into freelance with a slow start-up period. None of those things were necessary though. I just had to look for choices and make them.

2. Complexity is beautiful, but it’s a mask.

As a writer and lover of (most) all the human conditions, I like to navigate complexity. I look for all the influences and whys and evolutions and possibilities. But as I was processing my grief and cataloging all the things I wanted to accomplish before I died myself — what I wanted my life to mean — the complexity seemed to be covering very simple desires.

I wanted my husband and I to be able to have 8–9 hours of uninterrupted sleep most nights. I wanted to be healthier. I wanted better experiences — not necessarily better vacations or date nights, but experiences that would leave me excited and energized weeks later. I wanted to belong to a community, but not just any community, one that had meaning to me.

When I began asking myself why I didn’t have those things (I mean, they all sound like a matter of scheduling, right?), the answer invariably was that I was allowing all these complex excuses to shade the fact that they were just excuses. When I let go of the sources of complexity, I found very simple solutions.

3. Grief is a very real, solid object that takes up headspace.

Grief created a prism for me to see new sides of my family and closest friends, but it left me crying while I was driving and when people offered sympathy. Saying you were sorry for my loss was one surefire way to ensure I’d be tearing up within two minutes.

For weeks, I just didn’t want to do anything; I didn’t care. I was irritable, constantly reminded of all the things I’d never get to share with my mom. I was impatient with people around me and impatient to get through what I viewed as a process.

Months later, I view the grief I have now almost as a box with edges I can’t see. I can feel the space, feel an ache, feel waves of pain at an unexpected memory. But in general, I know where the box is.

Sometimes I choose to walk toward it because, after all, it is a part of me just like my mom is. I can walk away from it, too, though, and let other parts of myself flourish. This is probably the way it always will be, and I’m okay with that.

4. Life is a gift, and you’re only cheating yourself if you don’t treat it that way.

Sounds simple, right? If pressed before my mom died, I would have agreed with that statement. I shelter it as an unalienable truth now.

5. My mom’s life was so much bigger than me and the relationship we shared.

So much of who I am is shaped by my mom; many of the ways I gesture and enunciate reflect how she talked. She loved creating, whether it was improving her home, gardening, quilting, or ceramics. She obsessively focused on the fine details in each of these endeavors and doing them was almost as essential to her as breathing. I see much of that same appreciation and obsession in my own relationship with writing.

But as I’ve seen her through my dad’s grief, my aunt’s grief, and my brother’s grief, I’ve seen all the other roles she played and how much she meant to others, from high school friends to neighbors she grew close to in her 50s. I’m grateful for the opportunity to know her through them and am glad I never shied away from their sadness and their memories.

My mom lived a rich, full life, and I love sharing it all with her, even the parts I didn’t experience until she was gone.