Video Shows What A Day In The Life Of A Child With ADHD Is Like

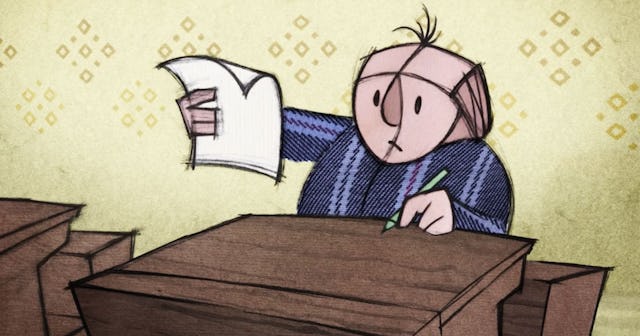

I’m scrolling through my social media feed when I see an animated film labeled a must-watch for those with loved one with ADHD. Intrigued, I click on the video entitled Falling Letters.

With each passing scene, I feel my heart beat quicken. The video has over 1.6 million views–for good reason. How did the creator so perfectly capture what ADHD is like from the perspective of the child?

I’m a mom of four, and one of my children has ADHD, as well as sensory processing disorder. After watching the video, I realized something important. As parents, we often center our feelings when our child is struggling, because we’re embarrassed or frustrated. But what about our child’s feelings?

Just that morning, before I viewed the video, I had dropped my oldest daughter at tutoring. Here’s what played out next.

We have an hour to kill, so I drive my other three kids to the library. Before I open the minivan door, I belt out reminders about using our inside voice and no running.

As soon as I open the sliding door, my kid with ADHD starts doing spins and karate moves on the sidewalk. I spot a library patron headed our way, and I ask my child to scoot toward me. I repeat my direction three times to no avail. By then, the patron has taken a detour through the library lawn. I sigh and hand my child the library bag, which is heavily weighted with last week’s books and movies. The heftiness of the bag can provide sensory input that calms my child. Today, it doesn’t work.

We make our way through the library doors and begin to climb the short staircase. My child is wearing flip-flops, which make bellowing echoes in the hallway. So much for being quiet in the library. We approach the circulation desk, where we’re warmly greeted by the librarians. My kiddo takes the items we need to return and says, “Catch!” to one librarian, before pushing hardcover children’s books through the drop-box slit–forcefully.

We then proceed downstairs to the children’s library. My child stops to play with the scanner at the self-checkout stand. I promptly remove it from their hands and place it back in the holder. I chat with the children’s librarians for a minute before rounding the corner to find my child playing with the rentable fishing polls and then reaching over to repeatedly click the nearby computer mouse.

I issue a firm reminder to choose two books and movies. Selecting DVDs takes a painstaking twenty-five minutes. My child knows the rule—only two movies are allowed. Yet there are hundreds to choose from. My kiddo proceeds to lay out about ten options in a line, right in the middle of the aisle.

Finally, I decide to do a countdown from ten, forewarning my three kids that I need them to make their final selections. The countdown stresses my child with ADHD, sending them on the verge of a tantrum. I get down on my knees and help select two movies.

My kids take their chosen items to the checkout desk, library card in-hand. But my child abandons the process within a few seconds, attracted to the lure of the playroom next door. The siblings follow. I can see directly into the room, providing necessary supervision.

I let my kids know that we only have about five minutes to play before we need to leave and pick up their big sister. I look over to see one of my children’s teachers playing on the floor with her granddaughter. We’re chatting away when all of a sudden I hear the unmistakable sound of crumbling plastic building blocks. My child is smashing block towers, Incredible Hulk style, over and over and over. I squat down and whisper, “Please be gentle.” But my child’s reality is that “being gentle” doesn’t provide craved sensory input.

This is just a 40-minute example of what ADHD looks like in a child from a parent’s point of view. And when I saw the new animated video, I embarrassingly realized that I’ve been so focused on my frustrations and struggles that I have rarely paused to consider what ADHD is like for my child.

The video doesn’t contain dialogue, but any parent of a child with ADHD knows what happens during those in-between moments. Our kids are labeled as distracted, impulsive, angry, aggressive, and loud. We’re told that ADHD isn’t real. Instead, it’s an excuse for a badly behaved, spoiled child.

Newsflash: our kids can hear you talking about them.

Why don’t we just medicate our kids? Well, some of us do. But medicating a child with ADHD is complicated. Common side effects of stimulants include difficulty sleeping and stomach issues. There’s also a risk of addiction. And there are also several medications with multiple dosing options. Medicating is a game of trial-and-error, and it can take weeks, months, or even years, to figure out the right medication and the right dose. Patients have to see their doctor frequently, and the medications are pricey.

Several people have suggested to me that my child needs more discipline. Maybe enroll them in martial arts class? Have we tried essential oils, CBD, or an omega-3 supplement? How about chiropractic adjustments? What about the Feingold diet which eliminates certain food ingredients including artificial food dyes, preservatives, and salicylates–a component in foods such as apples, grapes, and almonds?

What I desperately wish is that others could see all the amazing qualities my child with ADHD has, including friendly, polite, creative, and smart. And those “bad” qualities? While someone might deem my child distracted, I would clapback that kids with ADHD are noticers. While other kids might run past a flower, my child, like the one in the video, would take the time to examine it, pick, it, and use it to create something intricate and beautiful.

The end of the video is perhaps the most poignant. The child is picked up by his father, bringing a smile to both of their faces. The moment illustrates that the parent-child relationship — one that provides safety, love, and support — can empower the child and let them know they wonderful and worthy.

Yes, ADHD is a challenge for both the parent and the child. But Falling Letters reminds us to walk with our children, observing the beauty they have known all along.

This article was originally published on