Twice-Exceptional: My Son Is Gifted And Learning Disabled

I blamed myself. That’s the natural excuse: It’s my fault. You think this, especially when your child is gifted. If Blaise can read two grade levels above his expected ability, I thought, then I just didn’t do enough handwriting with him. I realized, with horror, that my 7-year-old didn’t know his lowercase letters. That his writing was labored and crabbed, and his spelling indecipherable. “Kaoak” meant cook; “lvoe” love. He couldn’t spell his own last name.

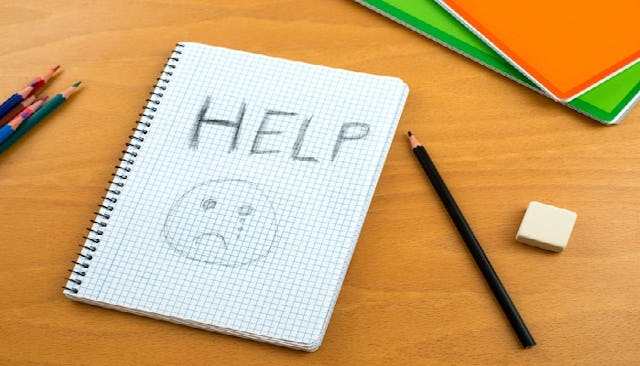

So we worked on it. Of all our homeschooling, Blaise only complained about writing. He’d sit at his table, pre-lined paper in front of him, and struggle to write three sentences of scrawl on easy topics. I picked things related to our other work, to our social studies or our reading, and talked about it with him beforehand. We brainstormed ideas. And still, it took him forever. He complained the whole time. And it was as if his grasp of phonics went right out the window when he picked up a pen. Yesterday, “avocado maki rolls” was spelled “moce rars” — this from a kid who can read “the department of education.”

Finally, I looked at his paper, with its inconsistent spacing, its creative spelling, its mixed upper- and lower-case letters, and thought, what if there’s something wrong? So I started researching and something came up: dysgraphia, or a problem with writing, possibly dyslexia. A diagnosis would explain Blaise’s disparity in reading and writing ability. A diagnosis would give us strategies to help him.

A diagnosis would label my gifted son as learning disabled (LD).

Blaise is what they call “twice exceptional”: gifted kids who also have a learning difference. I’d already gone through sadness and the worry when we realized he had the same ADHD that my husband and I suffer from. I knew the problems I had — the trouble with attention, the social issues, the hyperfocusing, the choice paralysis. And I see, firsthand, how my husband struggles with his learning disability, dyscalculia. Basically, he has dyslexia, but for math. He still occasionally counts on his fingers and cannot give accurate estimates of time or distance. Luckily, electronics balance our checkbooks for us.

So I worry, a lot, about what this diagnosis will mean for his life. With some strategies, I can help him to write. But it breaks my heart that he might never love it. That the art of putting words on the page may be a burden, rather than a pleasure, for him. That with all the compensation strategies and all the help, he might still struggle. No one wants their child to struggle.

We already have to talk to him about how he’s different. He goes to a homeschool co-op, and he knows how well the other kids his age can write. He knows what their handwriting looks like and knows how easily they can produce text. We explain that his brain works differently — he’s familiar with this concept from his ADHD. And because his brain works differently, I say, it’s harder for him to write than it is for other people.

“Maybe I just need to try harder, Mama,” he says sometimes. And it breaks my heart because trying harder simply won’t help.

“You can’t try harder,” I say. “You can try differently. That’s why we’re getting you an evaluation, so we know how to help you try differently.”

He hmphs because he’s anxious about the evaluation. Already, he’d begun to compensate: He’s gone from spelling on his own to asking me how to spell every. single. word. And still he comes up with “rars” for “rolls.” The words he thinks he knows, he usually misspells, down to “lvoe” for “love” and “fa” for “the.” Now that I can see the problems, I can’t unsee them. They make me sad, these little papers he labors over so hard. I don’t know what’s wrong, so I don’t know how to help him, and I’m frustrated. Nowhere near, of course, as much as he’s frustrated.

Luckily, the other kids around him haven’t noticed his writing yet. And if they have, they haven’t said anything. There’s a great tolerance in the homeschooling community for learning at your own pace, a tolerance I’m grateful for.

So now we wait, not-so-patiently, for a diagnosis. We need a label so desperately. A label will let Blaise say, “I have dysgraphia,” if someone asks him to write or if another kid makes a crack at his handwriting. A label will give us tools and resources to help him. A label will tell me how to teach him, hopefully, to enjoy writing, even if his handwriting isn’t wonderful.

We’ll work through this. We’ll learn how to help him, and he’ll learn how to compensate. He’s resilient. It might not be easy. But we’ll do it anyway.