Time-Outs Are Overrated And Ineffective

When it comes to parenting, I haven’t wanted to latch on to any one philosophy, and instead try to parent by instinct. So I co-slept and breastfed my kids for a super long time because it just felt right. But I also let them have an ungodly number of hours of screen time, vaccinated them without much thought, and have been more lenient about junk food than I would like to admit.

You get the picture: Balance and “whatever works” is my motto.

When it comes to disciplining my kids, I’ve done the same. I’ve tried sticker charts, allowance, yelling/not yelling, taking away privileges/not taking away privileges. I experiment with this and that, see what works, what feels right for each kid, and hope I’m not screwing things up too much along the way.

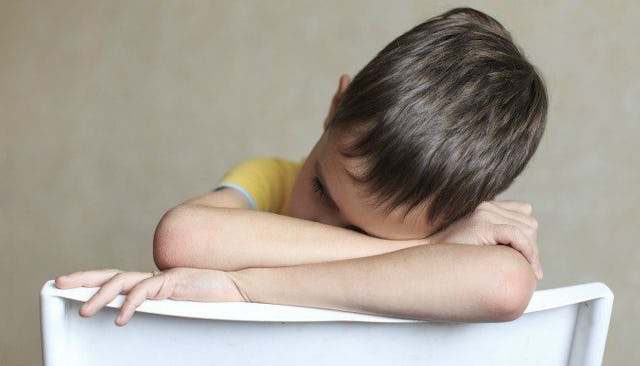

But one thing I have always been clear about is that we don’t do time-outs in our house. My instincts have always told me that isolating a kid who is misbehaving and already emotional seems somewhat cruel and unnecessary.

Now, I know that time-outs are hugely popular. Probably almost everyone who is reading this is thinking, “We’ve been doing time-outs for years, and they work fine.” Or, “WTF is this lady thinking?”

You might also want to tell me that time-outs are one of the kinder forms of discipline and that they work really well for most kids. Maybe you’re on the verge of punching me in the face for being so judgmental, especially when I just said that I don’t believe in didactic parenting philosophies.

First, let me clarify what I mean by time-outs. There are absolutely times that a separation from your whiny, cranky, rule-breaking kid can be a lifesaver. If your kid is being dangerous to themselves or those around them, they need to be removed from the situation pronto. And if they’re really resistant about being moved, sometimes you need to drag their kicking, out-of-control butt of out the room so they can CTFD.

Additionally, there are absolutely times when parents needs to get the hell away from their kids before they throw a lamp at them or yell so loud the neighbors will call the police. Stepping out of the room, placing your kid in another room, or walking outside and screaming into the wind are perfectly healthy and necessary things to do sometimes. We’ve all been there.

But if your kid is being a jerk, a sass, a rule-breaker, a whiny mess, or just plain acting out or being out of control in a non-harmful way, time-outs as a form of discipline sends them the wrong message, as far as I’m concerned.

When kids misbehave, there is something wrong. They are struggling. And whether they can express it or not, they need help. Time-outs force them into isolation and disconnect them from the very people who might be able to help them get out of their funk. They may be craving connection.

Dr. Daniel J. Siegel, a neuropsychiatrist at the UCLA School of Medicine, and Tina Payne Bryson, Ph.D., co-authors of The Whole-Brain Child, explain the problem with time-outs much more succinctly than I can, in an interview they gave about their research in Time magazine:

“Even when presented in a patient and loving manner, time-outs teach them that when they make a mistake, or when they are having a hard time, they will be forced to be by themselves—a lesson that is often experienced, particularly by young children, as rejection,” say Siegel and Payne Bryson. “Further, it communicates to kids, ‘I’m only interested in being with you and being there for you when you’ve got it all together.'”

As parents, we absolutely need to send our kids the message that certain behaviors are totally unacceptable. But we need to make it clear that we are rejecting their behavior, and not them. The thing is, kids can’t always tell the difference.

Now, I know that most loving parents aren’t intending to reject their kids when they send them to time-out. The trouble is, kids don’t know how to make that distinction. It’s impossible for them to rationalize the whole experience.

Siegel and Payne Bryson point this out in their research, explaining that feelings of rejection are felt as intensely as physical pain in the developing brains and bodies of children. “When the parental response is to isolate the child,” Siegel and Payne Bryson write, “an instinctual psychological need of the child goes unmet. In fact, brain imaging shows that the experience of relational pain—like that caused by rejection—looks very similar to the experience of physical pain in terms of brain activity.”

The writers also conclude that time-outs actually don’t work, at least not as a long-term solution. “Parents may think that time-outs cause children to calm down and reflect on their behavior,” conclude Siegel and Payne Bryson, “But instead, time-outs frequently make children angrier and more dysregulated, leaving them even less able to control themselves or think about what they’ve done.”

So what to do instead? The researchers suggest something called “time-in,” where you sit with your child, talking, reflecting, and calming.

Now, let’s be real. I love the idea of “time-in,” and it’s something that works for me and my kids often. But it isn’t going to work all of the time. Depending on his mood, one of my kids absolutely will not go for that for one second, and can be so upset and indignant that the idea of talking or reflecting would be a total joke.

So I’ve had to think of creative ways to manage his disruptive behavior when just “talking it out” doesn’t work, including removing privileges (for us, that would be screen time, always screen time), canceling plans, or withholding allowance. But these are always laid out with respect for his feelings, without threatening tones — and definitely without isolating him from me.

I think the bottom line with any form of discipline is that you have to be conscientious about how it’s presented to your child. Are you making sure that your child knows that whatever is happening, and whatever wrong they have committed, you are there for them, you love them unconditionally, and they are not inherently “bad” or “naughty”?

Disciplining kids is ultimately about teaching them lessons, and it’s vital that the lesson you’re teaching be positive and affirming. I don’t doubt that there are ways to do time-outs that are respectful of a child’s feelings, but if time-outs are all about threats and isolation and leave your children with feelings of guilt and shame, it’s time to ditch them and try something else.

This article was originally published on