Slavery Isn’t ‘Ancient’ History

My skin is dark. My hair is natural. And my story is complicated. My Black ancestors did not have it easy: ripped from their homeland in Africa, forced onto a crowded ship, and carried to a land to live with people, a language, and a culture they did not know. How scary is that? There is just so much to unpack there.

Sure, we can unpack it in the confined spaces of a seminar in college or in middle school with a bunch of tweens, but the real work around our American history and racism must be done both inside and outside of the classroom. Slavery has shaped our America into what it is today: a place where racism lives on, and continues to be passed down from generation to generation. An idea that Black people were (and are) the inferior race.

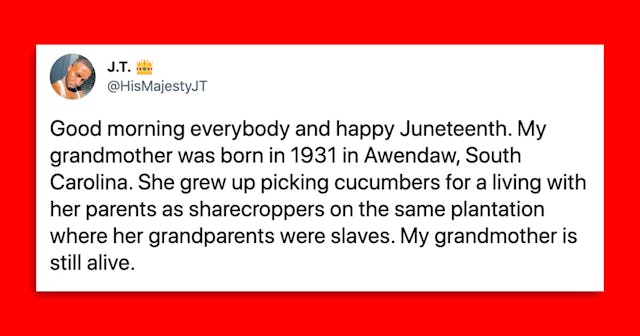

In a viral Twitter thread, @HisMajestyJT puts the timeline of slavery into perspective by pointing out that it wasn’t that long ago.

“I was born in 1986 10 miles away from that same plantation,” the thread continues. “That plantation is still standing … slave cabins and all. It’s not ancient history. It’s very real. And very tangible. My grandmother knew her grandparents who were slaves & worked the same land as them.”

As I begin to unpack my own family’s history in relation to slavery, so much makes sense. Black people have long struggled to fight for equity and equality. Over the years, I’ve learned of my own family’s connection to slavery, driving home the notion of “40 acres and a mule.” My grandmother’s family owned over 20 acres of land in rural Virginia. I always asked why and how we received so much land, but I never got a clear answer. As I dug a little deeper, I’ve learned that the land was apparently given to my great-great grandmother, who married her slave master. I’m still trying to dig up more of that truth. Was the land a way to make amends for his wrongs? Was it a way to help his wife (a former slave) create a life for herself? Back then, and even today, homeownership and land ownership remains a way in which Black people can build generational wealth. That doesn’t come easy though, as housing and wage inequities disproportionally impact communities of color.

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act ,which prohibited the discrimination due to race, color, religion, sex or national origin, became law. The law went a step further to also prohibit discrimination based on race in the workforce, and decreed that people could not be discriminated against during hiring, or fired, or not promoted because of their race. This was the same year my mother was born — not that long ago.

In an investigation of modern-day slavery by VICE, journalist Akil Gibbons conducts a harrowing interview with a man named Arthur Miller, a Black laborer forced to work against his will well into the 1960s. His story, and the atrocities he and his family faced, are heartbreaking.

Every Black person knows that there is still a great struggle today to be seen as equals. To not be judged by one’s name before you’re even brought in for an interview, or all the times Black men and women and children are followed in stores, for fear that they may steal, like I was at the age of 10.

Racism is a societal mainstay which has been around for centuries. Author of “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” Isabel Wilkerson, said in an interview with NPR, “[I]f caste is the bones and race is the skin, then class is the, you know, the clothes, the diction, the accent, the education, the external successes that one might achieve.”

We need to work together to break down a system which has defined who we are. Racism was born out of slavery, and is still a systemic issue. When Black people don’t receive adequate health care or maternal care, that is systemic racism. When Black folks are imprisoned at higher rates than other groups, that’s systemic racism. When homeownership is more challenging for the Black community, even to get a mortgage or sell their home for what it’s worth, that’s systemic racism. When Black kids don’t have access to educational opportunities like their white peers? You guessed it: systemic racism.

We can talk all day about the impact slavery has had — and still has — on our country, from how the prison system operates today to who holds the most wealth, to the police killings of unarmed Black people. The remnants of slavery are here with us today, and these remnants are what hold us back from moving forward as a society. Racism and racist beliefs will never truly be a thing of the past, but we can approach it differently.

In his book “How to Be an Antiracist,” author and scholar, Ibram X. Kendi says, “[T]here is no neutrality in the racism struggle … One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in between safe space of ‘not racist.’ The claim of ‘not racist’ neutrality is a mask for racism.”

We can have systems in place that combat racist beliefs, such as authorities, politicians, and cops who spew racist beliefs being justly reprimanded — and I mean losing their jobs, not simply being put on “desk duty.” When teachers or school officials push their racist agendas, they should be removed from their roles, not given a slap on the wrist. We cannot combat racism if we aren’t doing it together, if we aren’t all on the same page. Truth be told, eliminating racism altogether seems like an impossible goal. But how we deal with it and move through must change.

No one can deny the atrocities which happened during slavery: the murders, the lynchings, the rapes, the beatings, the selling of humans, the taking of babies and children from their families. And in the grand scheme of things, slavery was not really that long ago – which is why the Black community is still feeling its effects to this day.

As J.T. concludes in his Twitter thread, “Slavery is the very recent past. It’s contemporary history. No different than the Holocaust, the Titanic sinking, Vietnam war or the stock market crash. It should be treated as such. The blood is still on the leaves and in our veins.”

This article was originally published on