Here's What You Need To Know About The 'Problem Child'

I recently read an article in the New York Times entitled, “The ‘Problem Child’ Is a Child, Not a Problem.” It discusses how the appropriate method of behavior modification should be used by teachers to help “problem” children fare better within the classroom, especially in the earliest, most fragile years of their education.

The article itself was fabulous and extremely validating to parents of children with emotional and behavioral challenges. It recommended that teachers receive more training in adequate techniques to prevent situations like the one highlighted in the article — the case of an 8-year-old child having long-term emotional effects, subsequently resulting in educational challenges, from preschool teachers managing his behavior improperly. And it emphasized that poor behavioral management in early childhood can have lifelong consequences.

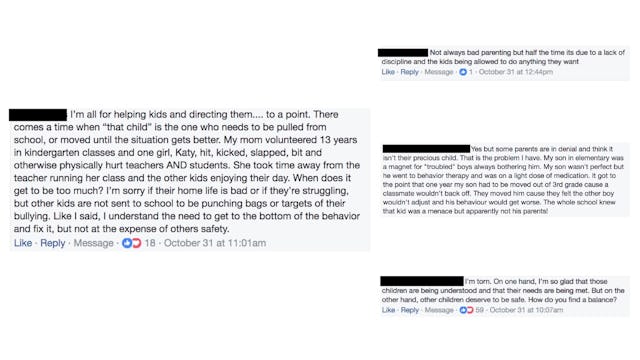

Unfortunately, I made the big — no huge — mistake of reading the comments. I have never been so blown away by a lack of empathy and sheer ignorance about this population of children. I am so angered and sad, but mostly, I’m disappointed and fearful. I’ll be the first to admit that much of the challenge with children like this is their behavioral functioning. However, another significant challenge is that the driving force behind such behavior is completely misunderstood. Here, right in front of me, was the glaring proof of such stereotypes — and not just any proof, but proof presented in well-thought-out and intelligent comments in the New York Times.

I am ashamed to admit it, but often, when I am out in public with my son, I find myself making justifications for his behavior in one way or another. An eye-roll to a person here to indicate, “I know, I know. I can’t believe he is doing that either!” or a harsher than necessary talking-to so others around me don’t think that I’m just ignoring such behavior — a behavior, mind you, that he likely cannot control and that my stern warning will do nothing to deter. I then find myself feeling terribly guilty: Why did I feel the need to defend anything my son is doing to anyone, nonetheless a stranger? Well, the Facebook comments section for this article also reinforced exactly why I feel such a need.

The comments fell into a few horrendous categories:

1. The “bad children come from bad parents” type of comments.

I hear this often — that a child’s behavior is the direct result of bad parenting. While yes, it is true that sometimes my 7-year-old simply acts like a 7-year-old, and in those moments, I probably don’t handle it to the very best of my abilities. I mean seriously, who parents perfectly all the time?

This is not what is going on for a child with ADHD. Most of the parents whom I know personally — and the thousands whom I interact with regularly as part of the vast support networks on social media — work tirelessly on their child’s behavior. We use behavior charts, talk to doctors, use family trainers, send our kids to cognitive behavioral therapy, and are just generally on their cases about every move they make all the time. We are stellar parents who have literally tried everything, including medication in many cases, and we still come up short. Why? Because our children are just wired that way and no matter how hard we work, we cannot completely deter the behaviors that come along with ADHD and other similar disorders.

2. The “parents should help the child — it’s not the teacher’s responsibility” type comments.

Most parents are doing all that they can with the resources available to them to help their child succeed in and out of the classroom. This is true for both the parents of special needs children and typical children. Even the mother of the child in the article stated that she would leave her child at school and then go and cry with worry. It is overwhelming to have a child like this in a way that is unimaginable to others unless they are going through it themselves.

Diagnoses that largely manifest themselves behaviorally are incredibly challenging to treat. Like a medical diagnosis, it cannot be treated in isolation. For behavior modification to be successful, every person who works with that child must be on the same page and consistent. I often say that “consistent” is my least favorite word — you try getting teachers, coaches, babysitters, grandparents, etc., to follow a specific plan on how to reinforce positive behavior in your kid. Any slight deviation in the behavior plan can have dire results. Something as simple as you attending to your other child and not providing the proper, immediate reinforcement can set you back days or even weeks.

A child is at school for a good portion of their day; if the teacher does not understand the behavior plan, then the child might as well not have it. Additionally, many of these behaviors directly impede their learning, and therefore require the direct attention of the teacher, the person who is responsible for educating them within the classroom.

3. This leads me to the next grouping of comments, the “children like this shouldn’t be in class with regular students” type comments.

These were the most hurtful comments of all. I completely understand where the parents were coming from; the comment was always based on the idea that these students take away from the learning experience of other, more typical children. That’s just disappointing and shortsighted. Let me be clear: I am hyper-aware of how my son’s behavior affects others, especially his peers, but separating him is not the answer — for any child. My son teaches others empathy and understanding. He shows them that not all children are alike. He demonstrates daily how one can overcome struggle. He is a good friend and a kindhearted and genuine child.

He adds to the educational experience of other students by requiring their help with reading and handwriting, and when students become the teachers, it is excellent for their development. He also adds to their educational experience by helping them with anything STEM-related. Many of the comments also expressed concern that these children take up too much of the teacher’s time. I get that — I want both of my children to get the time they deserve from their teachers. Some days they are going to be the children who require the time, and other days it will be someone else’s child.

4. The “children like this are just bad kids” kind of comments.

No, no, they are not. If a child is acting out, it’s for a reason. One person even went so far as to say that children like this were all psychopaths and that instead of teachers being trained in behavior modification, they should be trained in the early detection of such a disorder. I mean…really? When my son can no longer sit still or his hand is aching from writing due to his poor hand strength, he acts out. He’s tired, he’s 7, and he’s being asked to do something that he simply cannot do. He is not bad; he is just a child who is challenged daily by his ADHD.

The amount of parental blame in the comments was just startling. Attitudes and ideas like that only serve to alienate the most fragile of students and their parents. Instead of looking at the parents, we need to be looking at the public education system in its entirety. We are failing all students, typical and atypical.

Increasing the number of teachers per school and per classroom, and allowing for a smaller student-to-teacher ratio, would do wonders to allay concerns of all parents. Creating programs that allowed for more flexibility in learning modality instead of just focusing on the direct teaching method, would also benefit all students. Pouring money into our educational budget instead of slashing it to its bare bones would benefit all students.

We need to stop looking for the simple excuses and start focusing on better, more effective long-term solutions.

This article was originally published on