How "Fetal Personhood" Laws May Make It Harder For Women To Get Medications

“They are not going to play around with being held liable for harming a fetus that is now considered a fully legally protected child.”

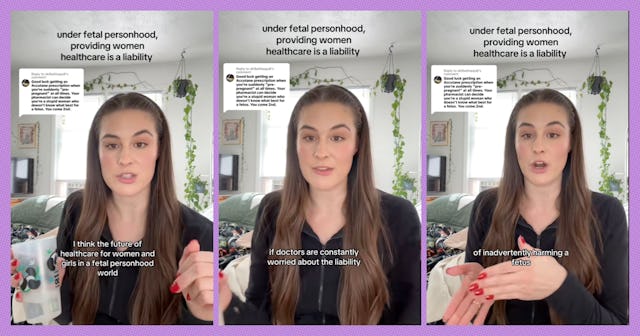

The intersection of pregnancy and women’s healthcare has been a widely discussed topic especially since the fall of Roe v. Wade in 2022 made pregnancy-related care, particularly in regard to abortion and miscarriage more complicated. One TikTok user, Ally Rooker, recently highlighted how the concept of “fetal personhood” — which extends full legal rights to zygotes, embryos, and fetuses and is currently recognized to some degree in at least 24 states— could further complicate this issue moving forward.

“I think the future of healthcare for women and girls in a fetal personhood world is going to look a lot like the Accutane model of pregnancy surveillance,” she says. “But scaled to a whole host of medications and treatments if doctors are constantly worried about the liability of inadvertently harming a fetus, who is now a fully legally protected child.”

Going on Accutane — a popular medication consisting mainly of isotretinoin used to clear up severe cystic acne — is a process, Rooker explains. This is due to the fact that any prenatal exposure to isotretinoin is very likely to result in severe birth defects, including underdeveloped ears, hearing and eyesight problems, heart defects, fluid around the brain, skull malformations including cleft palate, and even a lack of a thymus gland which is crucial in the production of necessary hormones.

As such, doctors generally have patients take a (negative) pregnancy test and go on some form of birth control (e.g. hormonal birth control pills, IUD) before they even begin taking the drug. Once on Accutane, patients continue to be monitored for pregnancy, including as TK notes, documented self-reporting of both pregnancy and birth control methods (at least two) and in-office pregnancy tests.

“They do not play around with being held liable for harming a fetus,” she says. “And they are not going to play around with being held liable for harming a fetus that is now considered a fully legally protected child.”

“Healthcare for women and girls is about to become the epicenter of pregnancy surveillance in a fetal personhood world,” Rooker predicts, positing that if fetal personhood laws expand — as has been both a strategy and goal for many anti-abortion advocates since the early 1970s — those capable or hypothetically capable of pregnancy could be seen has liabilities for medical practitioners, who may become more cautious in dispensing medications and services.

“We’re going to have to start jumping through so many hoops to get medications and treatments because we are no longer just a person, we are a shell around a fully legally protected entity that is a constant liability.”

Rooker’s commentary is speculative at this point, but it is not baseless. While Accutane-protocols are uncommon in most medications, could that change if laws around “personhood” became stricter? If a doctor could be held liable for even the unintentional death of an “unborn person,” would they be less likely to prescribe a medication that could even possibly affect a pregnancy? Or would they insist on intense monitoring, as with Accutane, to limit their legal culpability?

While fetal personhood is usually invoked in connection to abortion law, it has also been held up as a reason to cease IVF procedures. Last year, the Alabama Supreme Court allowed a couple to move forward in their suit against a Mobile-based fertility clinic for the accidental destruction of two frozen embryos. Due to the state’s 2019 constitutional amendment “recogniz(ing) and support(ing) the sanctity of unborn life and the rights of unborn children,” the court ruled that the couple could sue under the state’s 1872 Wrongful Death of a Minor Act. “Unborn children are ‘children’ under the Act,” wrote Justice Jay Mitchell in the Court’s majority opinion, “without exception based on developmental stage, physical location, or any other ancillary characteristics.”

While two plaintiffs have dropped the suit, one plaintiff remains. In October, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case, meaning the issue will continue to be one each state will have to deal with on its own for now. And while Alabama politicians moved swiftly to establish a law exculpating IVF providers from such lawsuits moving forward, uncertainties in the new law have already prompted at least one clinic to close its doors at the end of 2024.

And so it is not unreasonable to question what medical care will look like moving forward for anyone who could, hypothetically, be home to a legally separate person. As with many laws concerning women’s health, it promises to be an issue rife with complications.