Teen Gives Epic LGBTQ History Lesson In Pearls Protesting Florida's 'Don't Say Gay' Law

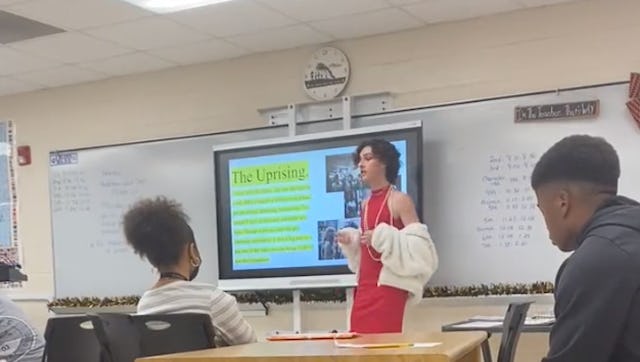

Will Larkins gave their classmates a lesson about the Stonewall riots with the approval of the teacher.

Just days after Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed the controversial “Don’t Say Gay” bill into law, kids are fighting back — and it’s inspiring to see.

In one Florida high school classroom, queer and non-binary student Will Larkins (he/they) decided that if their classroom was learning about 1960s and 1970s American history, they should learn about the Stonewall Riots — a seminal moment in the fight for gay civil rights. After a discussion, his teacher agreed to a 10-minute PowerPoint presentation, in which Larkins said gay a lot.

When they posted a snippet of the lecture to Twitter, showing Larkins in a white fur stole, a red floor-length gown, and a double strand of pearls, it went viral.

“LGBTQ American history is not taught in Floridas public schools, so I took it upon myself to explain the events of the Stonewall Uprising to my 4th period US history class,” Larkins tweeted this week, linking to a short clip of the lecture.

“We don’t learn queer history at all,” they told the Washington Post. “It felt like something important that needed to happen, especially with the legislation in Florida.”

The 17-year-old junior, who attends Winter Park High School in Winter Park, Florida, is not new to LGBTQ+ activism. They co-founded their school’s Queer Student Alliance, testified against the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, and led a 500-student walkout in protest of the same bill.

The response to Larkins’ history lesson has been mixed: hundreds of queer people and their families have applauded them — but others backed the law, which many have called vague, homophobic, and difficult to uphold. One of the biggest criticisms on Twitter was: why did they have to wear a dress? Was it really necessary?

Their response was perfect.

“Because I wanted to,” they wrote.

In March, the teen wrote a moving The New York Times op-ed about how the “Don’t Say Gay” bill would affect their life, as well as what their experience has been like growing up queer in Florida.

“From an early age I knew I was different. I wasn’t interested in the things other boys my age did, and I didn’t really feel comfortable in the clothes my parents bought me,” they wrote. “The struggle for acceptance was not just internal, it also felt as if my classmates didn’t know what to make of me. By fourth grade I was convinced that I was broken. I didn’t know how to defend myself when other kids made hateful comments or bullied me — I didn’t know why I was the way that I was. Without the vocabulary to articulate why I felt and acted like this, I assumed what they said about me was true. For most of the kids in my grade, I was the only kid like me they knew.”

They then wrote about how one of their teachers comforted them after being threatened with violence by peers — and she said she remembered feeling the same way when she was a queer kid growing up.

“Had the proposed law been in effect last year, my teacher could have put herself in jeopardy by being there for me,” they say.

Larkins, like so many others, think that education is the key to stopping hate and ignorance.

“I have come to realize that those who have been so openly hateful toward me often knew little about the queer community — they thought being LGBTQ was a conscious choice. Education didn’t just give me a sense of self worth but also the knowledge of a community and lifeline there for countless young people.” WHERE DID THEY SAY THIS?

Larkins told the Washington Post that their fight is just starting. They’re now working on voter registration for the November elections.

“We’re not going to stop fighting,” they explained WaPo. “As horrible as this all is, it’s inspired young people to get involved.”