My Life In Vogue

My town was mostly white. Most of my classmates were descendants of cold, Northern European countries. There was one Catholic church in the vicinity, but most of us were from cultures that valued thrift and tulips. My high school yearbook was full of Dutch and Swedish family names. The uniform of choice was a pair of corduroy Levi’s, topped by a button-down shirt and Shetland sweater, Topsiders on the feet. The girls who lived in the houses on the lake wore Lilly Pulitzer.

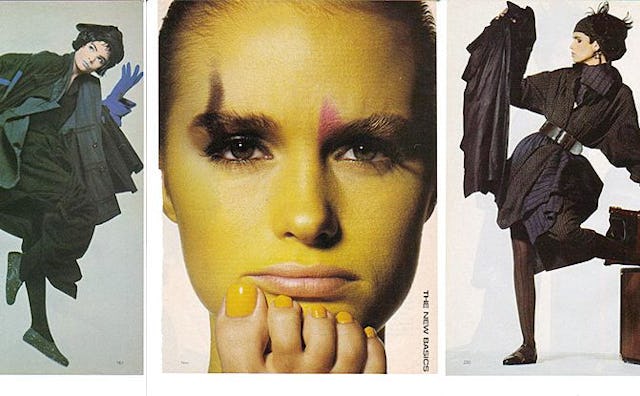

Meanwhile, I took my fashion cues from Vogue, which I’d started reading when I was 12. Not that I could afford the haute couture, but I was inspired by the lavish spreads, the romantic soft focus photography of Deborah Turbeville, the bold new ideas of young designers like Willi Smith and Perry Ellis. I’d ask my mom to drop me off at the public library while she ran errands, sit at a table with a stack of back issues and browse magazines all the way back to the ’60s and ’70s, when Diana Ross, one of my first style icons, was featured.

I’d first become acquainted with her through my Uncle Bob’s record collection. He let me spin Meet the Supremes and The Supremes at the Copa when I was visiting on summer vacations. Eventually, he gave his Motown collection to me. According to the paperback biography I kept on my shelf, Diana had grown up in a Detroit tenement where she killed rats with a bow and arrow and made her own clothes. The drama in her life made up for the lack of it in my own. If sewing was good enough for Diana, then it was good enough for me.

On a class trip to Detroit (Diana’s turf!) to see the musical Annie, I pretended to be a girl of means and browsed the tonier boutiques in the Renaissance Center. I tried on a linen Perry Ellis outfit for the feel of that fabric on my skin, to know the cut and drape of well-made clothes. A week or so later, I bought a few yards of pale pink linen and a Vogue pattern with my babysitting money, and stitched my very own Perry Ellis jacket and culottes, which I wore to school with what I thought was panache.

Inspired by Vogue, I whipped up jodhpurs in the softest baby corduroy, a zip-up lilac jumpsuit with epaulets, perfect with silver ballet slippers, and a plaid, ruffled, flannel mini-dress, which I wore with tights and cowboy boots. I made a turquoise Willi Smith mini-skirt with built-in pantaloons, and later a puff-sleeved top and skirt out of gray sweatshirt material à la Norma Kamali. Mostly, these outfits were too outlandish for the halls of my western Michigan high school. Instead of dressing down to fit in, however, I fantasized about getting out. I yearned for New York and Paris, cities where personal style was important and couture was a higher calling. I wanted to be a bohemian fashionista.

A brochure came in the mail, encouraging me to apply to a program to study design in Tokyo. Japan sounded cool. I’d seen the spread in Vogue of Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo’s clothes with their post-atomic tears and sculpted shapes. I wanted the clothes, but I didn’t think I had the skills to be a designer. I liked looking at beautiful things, and even making them while following directions, but if I had to create something on my own, well, I was better with words.

In my senior year of high school, I won a National Merit Scholarship and was interviewed by the local newspaper. I told the reporter that my dream for the future was to be an editor of a fashion magazine and to write books that kids would be assigned to read in school. In the accompanying photo, I’m wearing a drop-waist dress with a double collar in a tiny green check. I often wore this with a double strand of fake pearls, à la Coco Chanel. This dress had been selected from a pattern catalog by me, but sewn by my mother.

In college, I could finally wear whatever I liked without judgment. I sewed a billowy Issey Miyake dress and an architectural double-seamed white linen shift with a Japanese vibe. A female classmate asked to borrow it. Later, a male apartment-mate borrowed it without asking, and I never saw it again. I shopped at vintage boutiques, the church White Elephant sale, and the Salvation Army, filling my closet with little black dresses and paisley shirts. At night, I danced in a new wave club in the leopard-print jumper I’d run up on my Singer, accessorized with a wool fisherman’s cap and a rhinestone bracelet.

At 19, I made it to New York City, where I shopped at Love Saves the Day, the store that appears in Madonna’s first film, Desperately Seeking Susan, and to Paris, where I scored a red dress that hangs in my closet to this day, and then later, I came to Japan. When people ask what brought me here, I tell them that it was my love of Heian Court poetry. And, of course, I needed to rack up experience for the novels that I would one day write. And yes, I did write novels, including one about an all-girl band that performed covers of songs by Diana Ross and the Supremes. For the record, I didn’t become a fashion magazine editor, but some of my books have been taught in classrooms. Looking back, however, I think my coming to Japan may have had more to do with the designers I’d discovered in Vogue.

I was hired as an assistant English teacher at a high school on the island of Shikoku. With my first paycheck, I bought a black Issey Miyake jacket.

This article was originally published on