A 2-Year-Old Child Spent A Day In Immigration Court

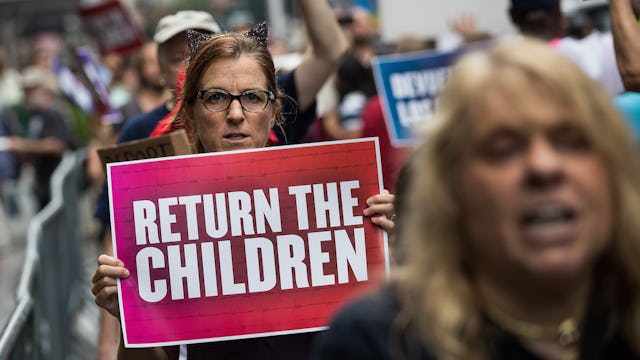

More immigrant children than ever are in government custody – and those separated from loved ones face immigration court totally alone

Despite the court order for all immigrant families to be reunited, more immigrant children are in government custody than ever before, and as the New York Times reported, some as young as two years old have to sit in front of a judge after long periods of waiting to learn their fate.

Times reporters Vivian Yee and Miriam Jordan spent a day at federal immigration courtroom No. 14 in New York, where 30 children, ages 2-17, had their cases heard in one afternoon. Some were there after being separated from loved ones, some were there after coming to the United States on their own, and all were suffering from a bottleneck of cases caused by the Trump Administration’s crackdown on immigration, the court order to reunite children with their family, and new stricter immigration controls implemented by the government.

Some children appear with only their caseworkers in tow, and some don’t even have attorneys.

The youngest was Fernanda Jacqueline Davila, a two-year-old who barely speaks any words, either in English or Spanish. Her maternal grandmother, Nubia Archaga, brought her across the border from Honduras, where she had been living with her paternal grandparents. She is the daughter of a teen mother and a father who died in a car crash before she was born.

Her grandmother just wanted to give her granddaughter a better life — but they were separated three days after she turned herself in to the Border Patrol, with Fernanda in her arms. That was back in July. Since then, the toddler has been living with her caseworker, who is contracted to care for her.

“I decided to bring her so that she could be in a better environment and have a better future,” Archaga told the Times, after she was released from detention. “I wanted the girl to have a better life.”

Fernanda’s case is easier to solve than most: she will be returned to her paternal grandparents in Honduras, who desperately want her back at home. But many of the children seen in court that day faced less certain fates, from deportation back into dangerous living conditions to months of detention before family reunions. It’s unclear how many will get the life their loved ones wanted them to have, or how many will not be reunited with loved ones.

Not even the number of children in the system is currently clear, though the Times estimates that 13,000 children who came to the U.S. on their own are currently being held in shelters, with hundreds still being held after being separated from family members.

“We rarely had children under the age of 6 until the last year or so,” said Ashley Tabaddor, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, to the Times. “We started seeing them as a regular presence in our docket.”

Kids too young to even go to kindergarten are now a regular presence in immigration court. Let that sink in.

Many of the children in the court along with Fernanda are represented by attorneys from Unaccompanied Minors Program at Catholic Charities Community Services, including Jodi Ziesemer and Miguel Medrano. Most stay in a shelter during the day — which is quickly becoming overcrowded — and then stay with foster families at night. Most don’t speak much English, and new research shows that many will suffer from post traumatic stress and mental health concerns later in life.

Because of the new government immigration controls, as well as the system’s poor record keeping, it’s unclear when, if ever, the issue of unaccompanied immigrant minors in court can be solved.

But for now, we are citizens of a country where a two-year-old was brought to immigration court by herself. So tiny that she had to be lifted up on the seat as the judge let out a soft murmur over her age. Her legs dangled because she’s too small to reach the floor. She began to cry.

Are we great again yet?