This Is What It's Like To Lose A Family Member To Opioid Addiction

The last time I saw my father was over breakfast, Thanksgiving Day, 2001. I was 19 and just out of high school. We met at a café within walking distance of his home. He’d been released from jail eighteen months earlier, but he’d yet to earn his driver’s license back. He’d made an effort to fix himself up, shaving his face and wearing a bulky green sweater. We met for breakfast because no one in the family wanted him over for Thanksgiving dinner.

Dad didn’t have any teeth. They had been pulled a few years earlier, and I always assumed it had something to do with his addiction to Vicodin. He smiled as I sat at the table, and I could see black pockmarks in his gums, cavities that used to hold teeth, but now held particles of food and other grime. His skin had the moist chalky tone of long drug addiction, his black hair streaked with gray and matted with grease, eyes sunk deep into their sockets, pupils blue-green and surrounded by nicotine-yellow and white.

Dad stood five feet seven inches and couldn’t have weighed more than 100 pounds, his skull pushing forward through a mask of skin and sparse hair like a stone near the surface of a river. He was 49 years old, but he could have easily passed for much older than that.

This was the leanest I’d ever seen him. The big meal he ordered and the bulky sweater he wore were all to make me think he was healthy. This was one of many ways he tried to hide his addiction. We talked about a few things that day. We talked about my mother. We talked about my job at the hardware store and the college I was attending. He asked me for money, and even though I knew he’d spend it on doctor visits to get more painkillers, I gave it to him because he was my father. Then I drove him to his fourth ex-wife’s home for Thanksgiving dinner because she was the only person willing to have him over.

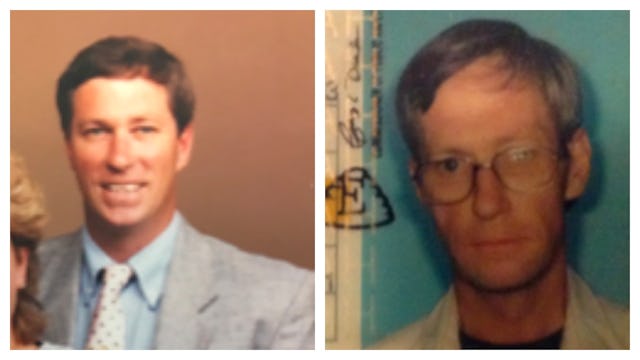

He died that next month, 10 years after several back-to-back work accidents left him addicted to prescription painkillers. From what I can remember, and from what I can piece together from family and former friends, my father was a pretty stand up man before those surgeries. He worked as a contractor, owned a business, paid his bills, and cared for his wife and children. But ultimately, our family doctor introduced him to prescription opioids, and it became a turning point in not only his life, but also mine.

I can remember my father driving off the road as he took me to a youth wrestling match. I remember him stumbling around the house, sleeping through the day, and going from one doctor to another, talking of pain, and always leaving with a prescription. I remember him walking out on my mother because she tried to find him help for his addictions, and then moving from one wife to another. Near the end, he never fully unpacked his belongings in each run-down apartment he rented because he knew he only had enough money to get into the place, and it was just a matter of time before they evicted him.

One of the most vivid memories of my father is of the two of us on opposite sides of bullet proof glass, talking through county jail telephones attached to heavy steel cables, me in high school, and he, once again, faced with a string of charges ranging from driving while intoxicated to forging prescriptions slips. This was a year before he died. He rubbed the phone with his palm, hand thin and spider-like, jaw moving from side to side, tongue mindlessly searching for teeth like the mussel of a clam searching for a lost pearl.

“I don’t want to see you in here. Ever. You don’t have to…You know that. You’re the good one. Better than me.” I felt so much empathy for him in that moment. He’d lost control of his body, and his life, and he didn’t want me to do the same. But losing control is ultimately what the opioid epidemic looks like.

I was 8 when my father’s addiction began, and I was 19 when he died. During those 11 years, I watched him go from a supportive husband, father, and business owner, to a sickly and easily confused drug addict. All of this happened nearly 15 years before anyone began to discuss the opioid epidemic. It happened when no one gave a second thought to what a doctor prescribed. My father’s addiction crept in on my family like a slow-moving poisonous gas that destroyed all his credibility, ruined his career, took his life, and impacted my childhood and understanding of fatherhood in ways that I still struggle to define.

In the beginning, I don’t believe my father went looking for drugs. He was prescribed painkillers from a trusted medical professional. Then he was given more, and more, until he couldn’t stop. Eventually doctors became drug dealers. All of it was legal.

He died in a one-bedroom apartment, alone, with little more than a small wardrobe of worn out clothes, a few dishes, and one family photo from when he was 10 years younger and healthy, a brown-haired young man in a bowtie smiling at his side. In his cabinets and drawers were enough prescription pill bottles to nearly fill a large black garbage bag, and I remember my older brother showing it to me as I hunched down in my father’s bedroom next to the mattress on the floor he died on, looking at that old family photo.

“Each one of these was prescribed by a different doctor,” my brother said. “Isn’t that crazy?”

“No,” I said. “It’s not. It’s terrifying.”

Yes, the opioid epidemic matters to us on a societal level, but when it impacts you on a personal level — when it’s your son, daughter, mother, or father — it becomes even more real.

When my father died, I didn’t cry as I cleaned out his apartment. I didn’t cry as I told his mother that he’d passed. I didn’t cry as I read the obituary in the paper. I didn’t cry at his funeral. In fact, I didn’t cry for almost a year. It eventually hit me when I was in the shower. It was evening, and as I sat down on the tile, knees in my chest until the water ran cold, I finally cried — but not because I’d lost my father. I cried because I knew he’d never have the opportunity to get clean, and become the father I knew he could’ve been were it not for his addictions.

But that is the reality of the opioid epidemic. For many, it is taking away their ability to be the fathers, mothers, and children they could be were it not for stumbling into addiction in the hands of a doctor. It means slowly watching someone you love die. It’s a trap that many blindly walk into, and we must all work together to see it stop.

This article was originally published on