White People—Get Familiar With The 'Late Student' Analogy Presented In This Twitter Thread

Hey, fellow white people, let’s talk about anti-racism.

George Floyd’s tragic death under a police officer’s knee has sparked a loud conversation about racism in the United States. Countries all over the world have joined in protest. The conversation about defunding the police in in full force. (BTW, that might not mean what you think it means).

Black activists, scholars and friends are being heard right now, loud and clear on an international stage, and some of us white people are truly listening for the first time. The message is clear: Even “nice” white people have more work to do. If you’ve been kind, that’s great. But it’s not enough. White people need to work to become truly anti-racist.

But if you’re getting involved in anti-racism for the first time, it’s important that you understand your role. White people, we can’t expect Black people to do the work of educating us, and we definitely can’t expect some kind of recognition for doing the right thing.

Our job right now is to study work that is already out there, and accept and understand white privilege. We need to quietly listen when Black people choose to speak on their experience, and then use our voices, our votes and our money to make things more equitable for everyone.

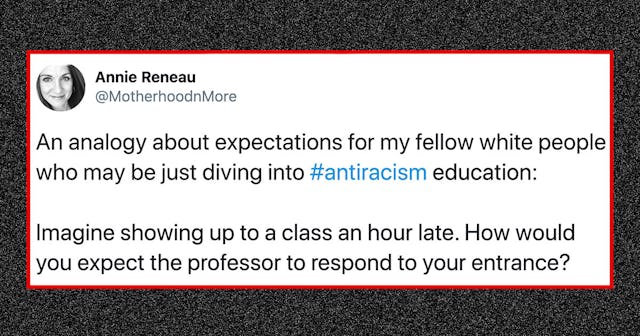

Writer Annie Reneau of motherhoodandmore.com, took to Twitter to explain exactly what white people should expect as we finally enter the anti-racism movement, long overdue. The entire thread is fantastic, but let’s hit the highlight reel:

She starts with a simple question:

Easy to answer. You’d probably just hope they barely noticed you, and quickly and quietly take a seat, right?

After establishing how you’d expect the professor to react, Reneau poses another set of questions:

“And how would you enter that class if you were an hour late?” she asks.

Would you waste valuable class time attempting to explain where you’ve been? Would you expect the professor to stop the class and catch you up? To most of us, that idea sounds absurd.

“OR,” she asks, “Would you quickly and quietly sit down, open your book, and do your best to keep up with where the class is now, knowing you’re going to have to catch up on the first hour’s material on your own (maybe borrowing someone’s notes to help with what you’ve missed)?”

Um, yes. That is exactly what most of us would do because entering a conversation way late is disruptive, and we know it. It’s on us to catch ourselves up, not on the instructor to backtrack. Makes perfect sense.

That’s not to say that if we are late, we shouldn’t show up at all.

“Would the professor be glad that you were in the class? Sure. Better late than never,” Reneau acknowledges. “But would you expect them to express gratitude or happiness that you finally showed up? Of course not.”

It’s unfair to expect Black people to thank us for finally realizing that anti-racism is more than just being nice. We should have made this connection a long time ago.

Nobody is saying if you’re late, don’t even bother showing up.

It’s critical to Black people’s survival for white people to start showing up. Late is better than not at all. But we need to understand our roles when we finally arrive.

Black people have been saying the same things over and over, and now we are finally jumping into the anti-racism conversation, dripping in white privilege. We just can’t expect them to start at the beginning to get us up to speed.

Many Black people have been down this road many times before.

As Reneau points out: “Imagine that [the professor has] seen countless students arrive late, sit down for a few minutes, decide the desk is too uncomfortable or the subject matter is too hard, then walk out, over and over and over.”

Would you have it in you to rewind, yet again, for someone who may or may not even truly listen?

We are very late to a very important discussion.

This Twitter thread uses the class analogy to explain so many important things white people need to know about our role in the anti-racism conversation.

Black people have no obligation to greet us with open arms or thank us for finally seeing them. Like a late student, we need to enter this space with some humility and respect for the instructor.

Spending our time on explanations and apologies centers our voices and drowns out Black voices. We might feel less guilty or embarrassed if we get to blather on about our own shortcomings, but the better choice is to keep our own words quiet, and amplify Black people’s words instead.

Because here’s the thing: If every Black person who is working to educate white people on their lived experiences is suddenly inundated with requests from recently inspired white people to go back and catch us up, then they can’t do the work of moving us forward. Black people don’t owe us the emotional labor of an anti-racism education from the ground up. The information already exists. They’ve been doing this work for hundreds of years. It’s our job to seek out our own schooling.

Reneau’s conclusion is as simple as the original question:

What can we do now that we have chosen to enter the conversation way too late?

Reneau’s answer? “The most respectful thing we can do is recognize our lateness, then quickly take a seat, open our books, and listen like someone’s life depends on it. Because it does.”

We can’t be anti-racist unless we are willing to take a quiet seat in the back and learn. That way, when we speak up, we will know what to say.

This article was originally published on