The Spoon Theory Helps Explain The Struggle Of Chronic Illness

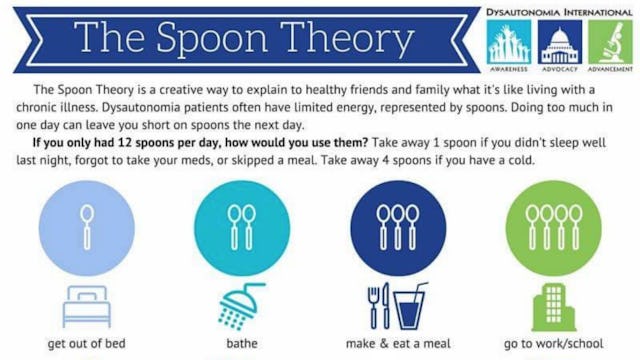

Christine Miserandino had been living with lupus when she went to a diner for french fries with her best friend. Her friend asked what it was like to be her, to suffer from lupus, and Miserandino grabbed a handful of spoons. She used the spoons to represent the energy she had during the day. Twelve spoons of energy are what she has. But her friend and other people without chronic illness? They have way more spoons. So many spoons. Spoons on spoons on spoons.

Every task that Miserandino completes requires a spoon. As she goes through her day, each thing she does causes her to lose a spoon. And when the spoons are gone, the only way to get more spoons is to rest and wait for her spoons to regenerate. Because of this, she has to ration her spoons throughout the day. If she goes hard in the morning and runs through her spoons, she doesn’t have any choice but to rest. No spoons, no energy.

If her friend goes hard in the morning? She might be tired or she might be fine. But in most cases, she can continue with the rest of her day because she has way more spoons. It might require a trip to Starbucks but a venti latte later, and life is still doable. Miserandino is careful with her spoons and tries not to waste them, but her friend doesn’t really need to think about her spoons at all.

This is the Spoon Theory, a concept developed by Miserandino and frequently referenced among those with chronic or invisible illness. Many people living with conditions ranging from fibromyalgia to anxiety to depression to diabetes self-identify as “Spoonies” and use the theory to explain their lives to people who may not understand the scope of their illness.

dysautonomiainternational.org

Because people living with chronic illness can appear “fine” and often don’t display easily-spotted physical symptoms, it can be hard for friends, family, and coworkers to understand why they bail on happy hour or can’t drive long distances for a visit or take so many sick days.

I suffer from frequent migraines and headaches. They are triggered by several different things, including stress, changes in the weather, and muscle tension in my neck and shoulders. My doctors haven’t been able to find one direct cause or an effective means of prevention.

Many days, I am operating with a constant, low-grade headache and may take over the counter medicine several times a day in hopes that my headache will go away. I try to rest during these days so that I don’t exacerbate the fatigue or tension in my neck and shoulders that can trigger a headache to become a migraine. Often, this only works to keep a headache where it is and not get worse.

Other days, I end up with a migraine that leaves me extremely sensitive to light and sound. At their most severe, the migraines have lasted for four to five days and only end when I finally go to the emergency room in the middle of the night because the pain is so bad I am throwing up.

As a working mother of two young children, a migraine usually disrupts life for my entire family. I may not be able to take my kids to school or on play dates with their friends. The television and computer become de facto babysitters because I, at least, know my son and daughter are likely safe if they’re zoning out in front of a screen. Sometimes, my husband has to leave work early or stay home all together to take care of me and the kids.

Because of this, I try to pace myself throughout the day. If I take on too much or try to do too many things, my neck and shoulders become stiff and I have to rest with heat on the muscles. If I am too busy in the morning and forget to eat breakfast while trying to wrangle my kids for the day ahead, I’m usually in bed by lunch and cursing at myself. If I don’t plan ahead and prepare for triggers, I am almost guaranteed to end up with a migraine.

My work piles up while I am sick and when a migraine finally goes away, I scramble to meet deadlines and complete projects during time I had hoped to spend with my family or doing something for myself. But I can’t even get right to my work because I need to rest and regain the mental and physical energy that my migraine depleted.

I do not look sick. I am varying levels of disheveled at times because my kids are 5 and 2 years old, so nothing too out of the ordinary there. To the outside world, people with chronic and invisible illness appear fine and it can be hard to understand why they cancel plans or why they’re always complaining about being tired. Spoon Theory has provided some context to share with the people in our lives so that they have a clearer picture of what we are dealing with.

This article was originally published on