As A Sonographer Who Has Suffered Stillbirths, This Is What I Want People To Know

Trigger warning: miscarriage and stillbirth

Once or twice a week, I tell people that I no longer see their baby’s heartbeat on ultrasound. I never expected I would be telling myself… twice.

I am a sonographer at a high risk OB clinic and I’m also a mom of two stillborn baby girls. When I tell patients I no longer see a heartbeat, I consider how I would want to be told after it happened to me. It’s such an unnatural feeling to lose a baby and it’s certainly not fair. An ultrasound could be the last way parents see their baby alive. Research from an obstetrics and gynecology journal stated that 75% of healthcare providers reported that caring for a patient with a stillbirth significantly affected them and took an emotional toll, while 1 in 10 even reported considering a different career path.

Even though I have very hard days, I continue to do the job I love so that I can comfort patients with my experience and my sympathy.

I scanned myself regularly when I was pregnant and because of that, found both fatal defects very early in the first trimesters for both girls. I scanned my firstborn once a week and, on Monday morning of week 10, I walked in to scan her first thing. I immediately noticed thick skin on the back of her neck and her heart was lower in her abdomen. I ran to get a coworker and doctor for them to confirm the news I already knew. She had something very abnormal; she was eventually diagnosed with limb body wall complex.

At the time, I had been working in obstetrics for five years. Limb body wall defects are rare, but most do not make it to the 2nd and especially not the 3rd trimesters. For that reason, everyone was unfamiliar with the prognosis. My baby is now a pregnancy that doctors would study to try to understand this rare diagnosis.

Cora had a 90 degree angle in her spine, her insides were on the outside and her heart was pulled down into the abdomen. If she survived, she would have multiple surgeries. I googled information just like any other parent who has a baby with something rare enough that the doctors have no prognosis. There is no known child living with limb body wall; it is considered “incompatible with life.”

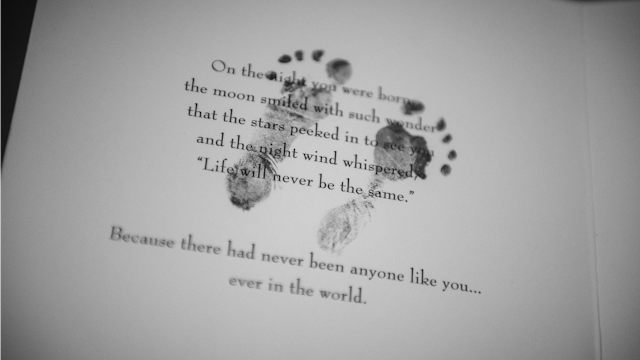

My husband and I started preparing for her death. We never fixed a nursery for her and when we had a shower, it was considered only a prayer shower with no baby gifts given. She was stillborn in July of 2013 at 29 1/2 weeks. We went on to adopt and have a rainbow baby all while I continued working at the same OB clinic.

In September of 2017, I scanned myself once again to find fatal defects on my own baby at only 7 weeks gestation. I had been scanning myself every few days to document fetal development for a blog post I was writing. The doctors wanted to wait until I was 9 weeks to officially call it, but I knew before then that my baby had acrania (akin to anencephaly). Layla’s skull never developed and her brain floated freely in amniotic fluid. I was in shock. Another completely random and rare fatal defect.

This time I had no doubt in my mind that it was 100% lethal. There would be no corrective surgeries. Babies do not survive this. We decided to try to donate her organs but all of those plans fell through when she was stillborn at 36 weeks this past March, one week before induction. We raised enough money to donate two cuddle cots to a local hospital and gave the extra money to the bereavement team for memory necklaces for loss moms to preserve our girls’ memories.

Sonographers are not nurses, but we are heavily involved with our patients. We find cancer, ectopic pregnancies, aneurysms, stillbirths, fetal abnormalities, internal bleeding, etc and we can’t always express our pain and grief for the person we are scanning. Because of this, people assume healthcare providers are jaded or cold, when in reality we hide our tears. We have to continue doing our jobs, even though we want nothing more than to break down right along with our patients. I have heard gut wrenching sobs from the ultrasound room and I feel it in my soul. I know that utter despair. I’ve had more silent delivery rooms than loud. I’ve buried two tiny white caskets.

So, if I hold your hand, call your name, and look into your eyes when I tell you that your baby no longer has a heartbeat, know it’s because I’ve lain there on that same bed with tears in my eyes hearing the same words. You may not know it, but you make us more compassionate providers and better humans.

This article was originally published on