Social Media Algorithms Are Sending The Wrong Message About The HPV Vaccine

In fall of 2020, The American Cancer Society began an emergency campaign meant to dispel misconceptions about the HPV vaccine and improve vaccination numbers. This came after research showed a 71 percent drop in 7-17 year olds visiting their doctors in light of the pandemic. The reduction in visits translated into a predictable reduction in vaccine rates. But the HPV vaccination was experiencing a decline even before the pandemic began, with a 70 percent reduction in rates year to year between April 2019 and April 2020.

That rate had dropped an additional 50 percent by May 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously to blame for some of these drops. But when it comes to HPV vaccinations being down even before COVID-19 hit, there may be another culprit responsible.

Monique Luisi, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, authored a recent study reviewing more than 6,500 public facing HPV-vaccine related posts on social media. She found that nearly 40 percent of these posts amplified the idea of a perceived risk surrounding the vaccine. And her data showed the posts had gained momentum over time.

With the HPV vaccination refusal rate being as high as 27 percent in some areas, and with enduring myths surrounding the vaccine, the last thing parents need is social media posts that falsely paint it in a negative light.

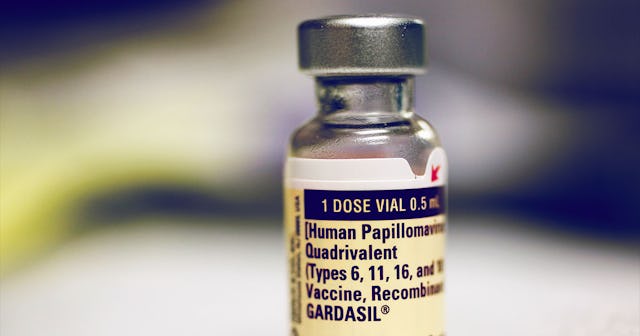

This is a vaccination that has been available for 15 years now, with over 120 million doses of the vaccine distributed thus far. Prior to being released, it was rigorously tested and found to be nearly 100 percent effective at preventing cervical cell abnormalities in girls and 90 percent effective against 4 types of HPV, including the types linked to genital warts and penile lesions.

As of 2016, the HPV vaccination had been credited with reducing HPV rates among teenage girls by 64 percent. And research has shown that if the vaccination rate could reach 80 percent, an additional 92 percent of cancers caused by HPV could be prevented.

Thitiphat Khuankaew/EyeEm/Getty

This is a miraculous, lifesaving vaccine that has proven to be safe time and time again over nearly two decades of research.

And yet, fears and misconceptions surrounding the vaccine have prevented far too many parents from getting their children vaccinated when doing so could be most beneficial.

So the last thing anyone needs is social media posts spreading false information about the HPV vaccine. Unfortunately, Luisi’s research has found exactly that to be happening.

In a study published earlier last year, Luisi identified social media as a haven for “anti-vaxxers” to spread their misinformation and gain traction among otherwise uninformed parents. Her latest study followed in the footsteps of her previous work, and helped to highlight just how dangerous these types of social media posts can be.

“It amplifies the fear that people may have about the vaccine, and we see that posts that amplify fear are more likely to trend than those that don’t,” Luisi said in a recent interview about her research.

This is likely due to how the algorithms work. The more comments and reactions a post gets—good and bad—the more people that post will be shown to. And when users see posts that back up their preconceived fears, they are more likely to interact with that content. Thus spreading it throughout their newsfeeds to others who may share similar fears and misconceptions.

Social media then becomes an echo chamber of information that isn’t based in science or fact, but that does back up the fears these users already held.

This translates to the COVID-19 vaccine, Luisi said, with the new rollout likely being accompanied by an onslaught of negative social media posts that could skew people’s perception of the vaccine itself.

The question becomes: how can we fight this spread of misinformation?

It’s not easy. People’s fears about vaccines, especially, seem to be deeply rooted in most cases.

But one thing socially conscious social media users can do is share scientifically backed information to refute the negative posts that may be spreading. Not everyone will listen, and users have to tread carefully in terms of how they engage in these discussions—name calling and insults are less likely to achieve positive results. But by continuing to push the importance of talking to one’s doctor and of looking to scientifically backed sites like the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) for information, users may be able to slowly dispel some of the myths and misinformation floating around.

Above all else, simply being aware of the impact of these negative posts can help users to identify and hide them when they appear in their timeline. Reporting misinformation can also limit the amount of views a post will get.

Perhaps most importantly, it is on us as parents to teach our children—the next generation—how to seek out scientifically backed information and how to use critical thinking skills when confronted with posts that don’t have research or facts behind them.

It may be too late for many of our peers, but hopefully our kids can enter adulthood using social media much more responsibly than we do.

This article was originally published on