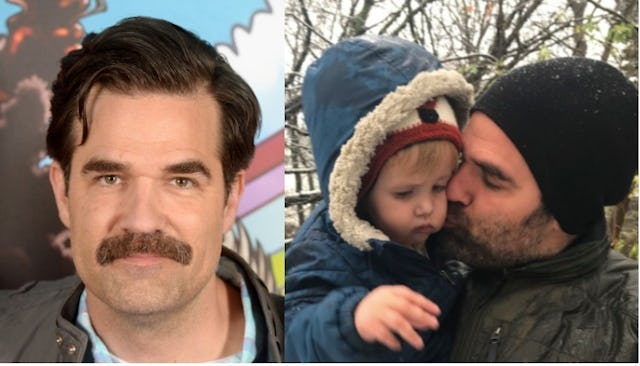

Rob Delaney Writes About The Death Of His 2-Year-Old In Heartbreaking Post

Delaney was writing about his son’s illness before losing the little boy only months later — this is part of what he wrote

This past February, comedian and actor Rob Delaney shared the heartbreaking news that his son passed away the month prior. Now, he’s sharing some writing he did while his son was sick, and it’s a haunting and unsparing look at what it’s like having a child with a serious illness.

He tweeted the link to his post on Medium with the caption “I hope this helps.” Reading the piece tells you who it is he wants to help — fellow parents of very ill little ones.

“I wrote all of this except the last paragraph in April or May of 2017,” he writes.

That was back when Henry was still very sick and about seven months before he passed away. Delaney explains later in his post that he was writing about the experience of having a child being treated for a serious illness with the intention of publishing a book to help other parents in their position feel less alone.

“The reason I’m putting this out there now is that the intended audience for this book was to be my fellow parents of very sick children. They were always so tired and sad, like ghosts, walking the halls of the hospitals, and I wanted them to know someone understood and cared. I’d still like them to know that, so here these few pages are, for them. Or for you,” he writes.

Throughout the piece, he details his son’s ever-worsening condition with his trademark heart and humor. Let’s not mince words here — Delaney’s writing is a complete gut punch. He describes his son’s illness in such vivid and heartbreaking detail — but he still brings jokes.

“He’s two. Despite the physical disabilities he has from the surgery to remove his brain tumor, he’s very sharp mentally and gets as excited about a big red double decker bus as any other little boy,” he writes. Delaney tells of his desire to bring his son on one of the London buses he has to take to get from the hospital where Henry is staying to another hospital to see some specialists.

He worries about bringing him on the bus because of what he needs to do to clear the little boy’s tracheotomy tube of mucus and then has second thoughts about that worry. “I’ll take him on a bus soon and if it makes anyone uncomfortable they can suck my dick.”

Delaney talks about his love for his sons and how happy it makes him to visit Henry in the hospital, despite the awful circumstances. The surgery to remove Henry’s tumor left him with Bell’s palsy, which caused one side of his face to droop. But the other side is still the baby that can light up a room. “And when he smiles, forget about it. A regular baby’s smile is wonderful enough. When a sick baby with partial facial paralysis smiles, it’s golden. Especially if it’s my baby,” he writes.

Then, Delaney tells the story of how the family discovered Henry had cancer. At his brother’s birthday party, he threw up. He was 11 months old and at the time, the parents thought it was no big deal — they had three sons, they knew vomit. But Delaney explains how the vomiting began to come and go, with the family seeing doctors and trying various antibiotics along with a visit to a gastroenterologist. The toddler was losing an alarming amount of weight due to the vomiting. Finally, Henry got to see a pediatrician recommended by a friend of their family. The doctor immediately landed on what might be wrong.

“He asked some routine questions but then he asked one that stuck out from the others: ‘Is his vomiting effortless?'”

“Effortless.”

“Yes, does he retch, or seem distressed when he vomits? Or does it just come up and out?”

“Hmm, huh, um, it is effortless, yeah. He’s not troubled at all.”

“Okay, I think we should schedule an MRI. Of his head.”

“Okay, why?”

“Just to make sure there’s nothing in there that shouldn’t be. Pressing on his emetic center, making him vomit.”

“What, like a tumor?”

He paused.

“I’m glad you said it.”

Henry had what Delaney calls “a real cunt of a tumor” and its location made it tough for doctors to fully remove it without damaging the child’s cranial nerves, which caused the Bell’s palsy and made him deaf in his left ear. The tracheotomy meant struggles with swallowing and gagging, which can cause pneumonia. The tracheotomy also meant Henry could no longer speak, a fact Delaney describes in heartbreaking detail.

“My wife recently walked in on me crying and listening to recordings of him babbling, from before his diagnosis and surgery. I’d recorded his brothers doing Alan Partridge impressions and Henry was in the background, probably playing with the dishwasher, and just talking to himself, in fluent baby. Fucking music, oh my God I want to hear him again,” he writes.

He then tells the story of a nurse helping replace the baby’s broken tracheotomy tube, and that’s where the post ends. Delaney explains why, and by now, anyone with a human heart is a sobbing wreck.

“I’m aware this ends somewhat abruptly. The above was part of a book proposal I put together before Henry’s tumor came back and we learned that he would die. I stopped writing when we saw the new, bad MRI. My wife and his brothers and I just wanted to be with him around the clock and make sure his final months were happy. And they were.”

Delaney says he may still write a book, but for now, he knows where he needs to be. “Maybe I’ll write a different book in the future, but now my responsibility is to my family and myself as we grieve our beautiful Henry.”