I Asked My Mother And Grandmother What They Remembered About The Polio Epidemic Of The 1950s

“Everything changed after your best friend Maria died,” my mother said.

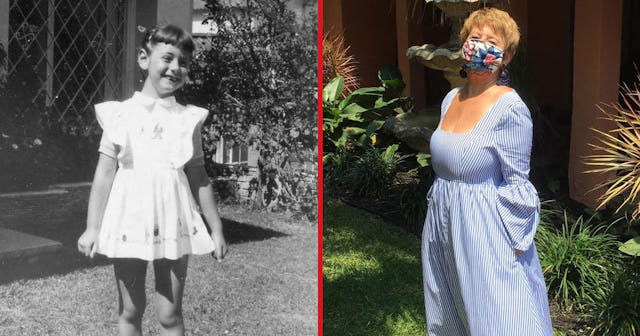

In 1976, my grandmother, my mother, and I were looking at old picture albums. When we came across a photo of me at age five in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1955, we stopped to reminisce.

“It was a bright day in October,” my mother continued, “and I remember the school called to tell me all the students had to go home. Polio. Polio had taken hold and several students were diagnosed. I picked you up, sure that everything must have been a mistake. The next day Maria died and I thought I would lose my mind. They told us it was a virus and there was nothing to be done except keep you away from all other children. No children could play with others. And we needed to monitor you for symptoms. I was so afraid, and no one seemed to understand what to do. I just looked at you—at your happy little face—and worried and fretted.”

My grandmother chimed in: “As soon as I heard the panic in your mother’s voice on the phone, I came right away. We were all of us at your house for weeks. Each day we would hear of a new tragedy.”

Courtesy of Sylvia Baer

I remembered some of this vaguely, but had never heard them recount it so vividly.

“You had a favorite dress that was too small, but you always wanted to still wear it. I would never let you do it. But during that time, I told you you could put on whatever you wanted. You were so delighted and wanted us to take your photo. Here it is.”

My mother pointed to me smiling in a very short pink pinafore dress.

“How did you manage that stress? The fear? The isolation?” I asked them both.

My mother turned to my grandmother and (uncharacteristically) let her speak. “I reminded your mother that in 1928—we were still in Poland then—she had typhus. She was five years old. Others were dying and no one knew from where this virus came. All we could do was stay home. Isolated. Your mother was terribly sick, and I was terrified. My mother-in-law came to help. And there we were, alone for weeks—separated from the rest of the world, nursing your mother back to health and trying not to get the virus ourselves. Everyone in the town was quarantined. No one came out of their houses for more than simple groceries. Very little was left in stores, but it was enough. Eventually, she got better, they discovered where it came from, and we all slowly began life outside the house.”

I was astonished that the two of them had such similar experiences of virus attacks and isolation.

Courtesy of Sylvia Baer

“It was terrifying, yes,” my mother said, “but we learned something important. We learned that at times like those there is still life. At first we did nothing but wait and watch, but then we realized that we had life and the important thing was to have it, not to lose it by fear.”

Now my grandmother nodded agreement. “My mother-in-law told me that the biggest sin we could commit was to act dead when we were still alive. She would sing raucous country songs and we would laugh and dance. We drank a lot of tea and she would tell me stories of the old days. I found out that life doesn’t stop because you are forced inside.”

“We were so lucky that you did not get sick,” my mother said. “After a few weeks, we ventured out again, and you began playing with other kids. Slowly my fear subsided. But when I look at your picture, I don’t remember that time as lost—I remember that I learned more about how to live.”

So here I am in our own scary time in America in the year 2020, and I think about these stories my mother and grandmother shared with me. I’m at home fretting. Fearful of what’s to come for myself, my family, my community, my world. Most of us are practicing self-isolation and it sometimes feels like time lost.

But it’s not. I remind myself: No matter what your circumstances, the only time that is truly lost, as my great-grandmother, grandmother, and mother taught me, is the time you forget to live.

This article was originally published on