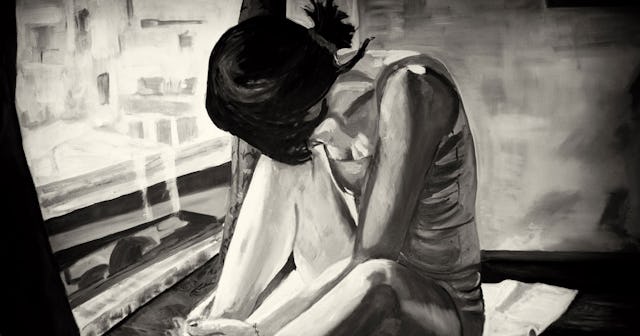

After My Daughter Died, My Grief Literally Felt Like A Heart Attack

Trigger warning: child loss

On the morning my daughter died from SIDS, I stood with my bare feet against the hospital’s cold floor, experiencing chest pains, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, and shortness of breath … all classic responses in the wake of trauma and brand new grief, but in a unit crawling with ER nurses and a few doctors, not one person thought to ask how I was physically feeling.

I went to my OB’s office a little over 24 hours later with a chief complaint of, “I think I’m having a heart attack my pain is so great.” To no one’s surprise, my blood pressure was through the roof. The nurse practitioner insisted that I stay in the office to eat some crackers, drink some water, lay on my side, and sort this whole high blood pressure thing out.

The differences in the way I was treated at both facilities left me with a sour taste in my mouth for the local hospital where my daughter was pronounced deceased. How could they be the ones to tell me my baby died, only to send me home without any resources that could help me navigate my new life?

In a 180 degree turn of events, leaving my OB’s office gave me some light at the end of my tunnel. Though I couldn’t see my usual provider, I was given the personal phone number of the nurse practitioner who examined me, a print-out full of symptoms instructing me when to call my doctor, anxiety medication for the panic attacks, and a list of nearby child loss resources to keep on hand for when I was ready.

On that half-hour ride home, I couldn’t help but keep thinking to myself, this is how it should be for all who grieve.

In those delicate first days, the bereaved can experience a wide array of worrisome, physical symptoms, some of which should not be ignored or taken lightly (chest pains, high blood pressure, extreme headaches, dizziness, fainting, and suicidal thoughts, to name just a few).

Malte Mueller/Getty

According to a cardiovascular study with nearly 2,000 participants, the bereaved were 21 times more likely to suffer a heart attack within the first 24 hours of loss, six times more likely to suffer a heart attack within the first week of loss, and at an increased risk to experience a decline in overall health over the course of a month.

“Caretakers, healthcare providers, and the bereaved themselves need to recognize they are in a period of heightened risk in the days and weeks after hearing of someone close dying,” Murray Mittleman, preventative cardiologist and epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston says in a statement.

Jessica Zimmerman is an LMHC specializing in EMDR therapy (eye movement desensitization and processing, a form of psychotherapy) and owner of Willow Tree Counseling. She explains to Scary Mommy that grief heightens cortisol levels — a hormone responsible for regulating metabolism, memory formation, controlling blood pressure levels and releasing inflammation.

“These physical changes in the body due to emotional stressors often lead to physical health problems,” Zimmerman says.

Besides the increased risk of a heart attack, grief weakens the immune system and inflames the body, giving once-dormant health conditions the opportunity to become active, and new conditions, such as autoimmune diseases, chronic pain, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases, the chance to develop.

There are no nationwide protocols for managing the mental and physical health of the bereaved in the immediate or latter phases of grief, but perhaps there ought to be. It took me a year and a half to learn about how my grief was affecting me, and that was only after I felt it wearing and tearing on my body.

Almost overnight, I had become “that person” who wound up sick more frequently than usual. Since my daughter’s death, I’ve had two surgeries from seemingly out-of-the-blue health conditions. And if that’s not enough, I was given a diagnosis of high blood pressure just this year.

This is the physical side of grief that nobody talks about… falling sick more than usual, cold chills, night sweats, extreme fatigue, vomiting, headaches, diagnoses after diagnoses, and physicians who overlook physical symptoms, attributing them solely to grief’s emotional pain.

America fails to provide education that’s been proven effective in the health care system, and the result is that the bereaved are denied preventative care to benefit their own health.

Zimmerman says that with a support system, therapy, taking time for one’s self, and developing a treatment plan with care providers, individuals who are grieving have the potential to positively impact both their short- and long-term mental and physical health.

Early intervention is key. This might mean intervening in the acute stages of grief, or even on a consistent basis throughout the many linear patterns of grief. Despite the manner of occurrence, the physical symptoms are impossible to treat if the bereaved and their care providers don’t understand, or won’t acknowledge, the physiology of grief.

As the saying goes: “The only cure to grief is to grieve.”

This article was originally published on