No One Brings You A Casserole When Your Child Is An Addict

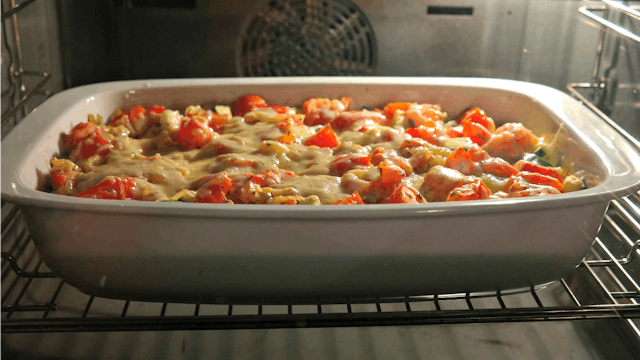

I remember when I was 15 years old and my grandfather passed away of cancer. Friends and family brought over casseroles, pies, and lasagnas. Warm cookies left on the porch and neighborly visits of talks and coffee. My mom needed that support. She was able to work through some of her grief without having to worry about making dinners and going grocery shopping. It was my first experience with a community coming together to help a person who was going through a very difficult time.

Years later, my own friends and I would do very similar things for those struggling with something — food was dropped off on the doorstep of a friend who was diagnosed with breast cancer, another friend who had lost her father had food delivered to the funeral home. “If there is anything I can ever do to help….” were words spoken and truly meant. When someone experiences grief and trauma, we come together to bring comfort food. It’s a beautiful thing.

But not when your child is an addict.

Opioid addiction is considered a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive drug-seeking behavior and drug use despite harmful consequences. Opioid addiction is federally described as a progressive, treatable brain disease.

What is the common theme here? Brain disease. Yet, as a society, there is such an enormous stigma attached to addiction that we don’t treat it as such. People tend to shy away from something that is so taboo. It’s the whispered disease. If we do talk about it, it’s behind closed doors.

It’s one of the main reasons why families who are going through it stay quiet.

I remember when my daughter Brittany went to California for treatment. She left right before Labor Day weekend when our family usually goes up to our cottage for the annual Turtle Races. It’s a big event, and the entire extended family attends. How could I explain her absence? I was scared of them knowing. Scared of the possible judgment, the uncomfortable look in their eyes, answering questions that I didn’t have answers to. I also wanted to protect her. What if she came out okay? I was paralyzed by my fear of her being scarred.

John and I felt very alone. When you are going through something of such enormity, you feel isolated. I could barely function. Getting out of bed was a chore in itself, let alone making dinners, grocery shopping, trying to live normal. Hours upon hours were spent on the phone with insurance. Sleepless nights not knowing where Brittany was, my heart gripped with fear every time the phone rang or a siren was heard.

At the age of 19, Brittany went into her first treatment center. I couldn’t breathe. I was beyond distraught. This can’t be happening! I could barely drive the 1 ½ hours home. I had to pull over a few times, my vision blurred with tears. When I came home, I collapsed into bed. Overcome with emotion, exhausted from the previous days of convincing her to go.

No casseroles were brought.

At the age of 20, she was admitted to a psychiatric facility and diagnosed with bipolar disorder. I spent days at the hospital, eating Cheez-Its out of a vending machine, while my family at home lived on peanut butter and jelly.

No tin foil pans of lasagna were left on the porch.

For seven years, as a family, we fought to save Brittany. Putting out fire after fire, dealing with one crisis after another. Flying all over the country to find the best facilities, the best doctors, researching, and arming ourselves with education.

Certain types of pain can feel invisible or hidden by families — mental health and alcoholism, miscarriage and infertility, job loss, a parent’s slow decline. The need for communication, support, and the comfort of a homemade meal isn’t as apparent, or may not even be known.

I didn’t write this as a criticism of my loved ones. They didn’t know what we were going through. I didn’t communicate how our family was crumbling. Because I was scared. But I was beyond blessed to have an incredible support system — once I finally talked about it.

Different kinds of crisis and grieving are more difficult for those who love us to understand and to comfort. It can be uncomfortable, and we tend to shy away from topics, events, or things that are out of our comfort zone.

If you know someone who is struggling, a few warm cookies on the porch may be just what they need to feel accepted, loved, and understood. Offers of coffee, cake, and a chat could be what saves their sanity. We all just want to be loved and accepted, no matter what we are going through.

If you or someone you love is struggling with addiction, there are resources that can help you.

If you’d like to reach out to Katie, you can do so here.

This article was originally published on