Timeouts Work For Older Kids — If You Do Them Right

Taking a moment to pause from big emotions is a coping mechanism kids can learn.

Years ago, I was in the middle of moving and asked my therapist if she had any advice for setting up our new house. She gave me two brilliant suggestions: Put my boys’ belongings in every room in the house, so they know they belong everywhere, and create private spaces throughout the house to encourage healthy alone time.

Not long after we moved in, one of my boys started having intense mood swings. He was only seven or eight years old, and sometimes he would get so upset he would just shut down or lash out. As a social worker, I knew the research on timeouts was mixed, but as a mom I knew my son would benefit from them.

Timeouts can be harmful when they’re used as a disciplinary strategy. Kids need help processing big emotions, and that can’t happen when they are forced to be by themselves. When timeouts are a consequence for bad behavior, kids can associate acting out or speaking up with a fear of isolation, abandonment, or rejection. Timeouts also tend to last too long. Experts say if you use timeouts as a discipline strategy, they should be 3-5 minutes, max.

That’s not the kind of timeout my son needed. He needed the other dictionary definitions — a pause from activity; a brief break. I could see how much he needed a way to calm himself down before connecting with me, but while also knowing I was close-by for comfort. My son takes after me; he doesn’t like to be touched or to talk when he’s really upset. In his case, immediate intervention like hugging or forcing him to talk about it was counterproductive.

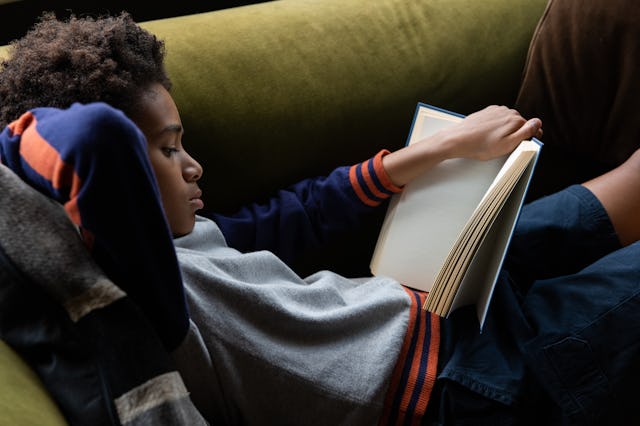

Together, my son and I reimagined what a timeout could be, working as a team to create the conditions of time and space that would let him calm down, cool off, and collect himself when he was upset. These sacred spaces ended up helping him feel ready to talk and process through whatever was going on. Back then, he chose the comfiest couch in the living room to be his “timeout spot,” and hid a box of books and art supplies behind it. We agreed he could give himself a timeout when he needed it. It was something I could suggest, but not require. It would never be a consequence but was reserved for rest and restoration. We both agreed that timeouts couldn’t last forever, and decided that a half-hour was the max.

The second grader is now a tween, and today he continues to give himself timeouts. He’s able to tell me when he needs time alone, and I trust that he’s telling the truth. His timeout spaces have expanded beyond our comfiest couch. Sometimes he goes outside to play basketball. Other times, upstairs to read a book. I might find him drawing at his desk or curled up on a couch looking outside. In our house, timeouts are not a time to be on tech. We just haven’t found it to be a helpful coping or calming down strategy.

Today, when my son calls “timeout,” my respecting that request brings us closer together. We both have learned that choosing alone time is different from being forced to be alone. Over time, we’ve learned how long timeouts should be, and what it feels like for him, when he’s ready for his break to end. Also, he knows what my discipline looks like, and that his timeouts aren’t it.

Our tweens and teens have plenty to be anxious, stressed, and sad about. Many are walking around exhausted, overstimulated, and needing permission to relax and recharge. Timeouts help. As parents, we can let our tweens and teens know they can call “timeout” from the busy of their schedule, from an especially heated argument, and from emotions or sensory inputs that feel hard to handle. When we give our kids the chance to call timeout, we create a way for them to feel valued and seen, to attend to their own health and wellbeing needs, and we equip them with a tool that can last a lifetime.

Stephanie Malia Krauss is a mom, educator, and social worker. She is the founder of First Quarter Strategies and the author of Making It: What Today’s Kids Need for Tomorrow’s World. Her next book, Whole Child, Whole Life: 10 Ways to Help Kids Learn, Live, and Thrive will be released in 2023.

This article was originally published on