All I Really Need to Know I Learned in a 1970s Open Classroom

I entered kindergarten in Potomac, Maryland, in 1971. This was just in time to become one of the first and last public school students in the U.S. to experience the enchantments of an open classroom education. No one really knew what the outcome of this experiment would be. They simply thought it was worth trying.

RELATED: What Is Classroom Management, And How Can You Apply It At Home?

My school, Lake Normandy Elementary School, was constructed more or less in the shape of a flower, with each petal—called pods—housing a different grade or mixed grades, color-coded by carpeting. Aside from the closed doors blocking off the third grade open spaces from K-2s’, there were no walls in my first pod as a kindergartener, just a vague notion of where one trapezoid-shaped classroom might end and another might begin, but really it was fine to wander. That was the whole point: the freedom to wander.

In the center of the flower, where the stamens would be, was the school library. It was the heart of the school, open walled like every other space and well-designed for maximum browsing. You nearly always had to pass by it or through it to get from your pod to anywhere else, like the cafeteria or bathroom, the latter for which you were never required to have a pass or ask for permission to go. If you had to go, you just went.

We’d start off the day in the open area in the center of the pod, where one of our long-haired, hippie teachers would play guitar and lead us in song. “Joy to the World” was our daily prayer. “If I Had a Hammer,” our philosophy. “Puff the Magic Dragon” and “The Marvelous Toy” would spark our imaginations. We once had a contest to see who could draw the most marvelous toy. I didn’t win, but I loved seeing how everyone’s toys and imaginations were so different.

Even today, when I’m baffled by someone’s diametrically opposed take on a similar event, situation, or relationship, I immediately remember that vast panoply of marvelous toys.

After the state-mandated Pledge of Allegiance—which felt silly in light of all of the free-thinking songs that came before—we were set loose into our pod, knowing only that between Monday and Friday we had a certain number of educational tasks that needed to be completed, in whatever order suited our learning styles and desires. Each task was explained at a “center,” a construction-paper covered easel with worksheets and materials explaining the challenge at hand: Figure out which one of these five objects floats; pretend you are a pioneer: what is your day like?; add these numbers; color in this map of the U.S., pick a state you want to study, and tell us something interesting about it; write your autobiography; learn how to crochet.

Periodically, you’d have a five- to six-person reading group, sorted by reading levels and led by a teacher, but with math you were pretty much left on your own: Follow the instructions on the assignment sheet and figure it out for yourself. If you got stuck, you could always flag down a teacher and get one-on-one help, but you were encouraged to do as much thinking and processing of numbers and problems as you could on your own. I taught myself how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide. I’m still proud of this. I needed a little help understanding fractions, but seriously, who doesn’t?

What all of this freedom and self-teaching meant, on a day-to-day basis, was that each of us was given both the opportunity and responsibility for getting our work done on our own schedules. If I wanted to do a big push and finish everything by Monday afternoon, which I sometimes did, I could. This left me with Tuesday through Thursday to focus on other things: I could sit in the library and learn about space travel; I could wander over to the fifth grade pod and bone up on cursive; I could write a short story or draw a picture or sit with my friend Ellen, memorizing the digits of Pi and seeing who could recite them faster. By allowing us to find what it was we were interested in doing when given the time and choice, we learned not only what we liked, but who we were.

This combination of time-management skills mixed in with an underlying notion of choosing books or tasks that would spark our interest enough to be worthy of that time has been the most valuable teaching I’ve carried into adulthood. Today, for example, I work here full-time at The Mid, but I’m also working on a TV show, three books, the art for those books, and several freelance assignments, and I have a photography business on the side. Sometimes the number of tasks I have to get done in any given week spins my head, but those lessons from the early ’70s have stayed with me: You just go center by center, step by step, task by task, and somehow it all gets done. Stressing out is useless. It eats time and mental energy. The work and the process of doing it are everything.

When I arrived in junior high school in seventh grade and was suddenly made to sit in a classroom with a teacher in front of it, I felt imprisoned, thrust out of Eden in the most violent of ways, except in English class where our teacher, Mr. Gillard, sat us in groups for greater ease of the discussion of literature. Aside from the periodic enlightened teacher like Gillard, the rest of my education up until college was torture. I did well, because that’s who I am, but it was still torture, and it killed my curiosity until college.

I’ve watched my children suffer through similar torture, particularly my daughter, now a senior at a prestigious public high school in the Bronx, which took my curious child and turned her into a stressed-out, grade-conscious automaton. And she didn’t even have the benefit of an open-plan elementary school as a baseline.

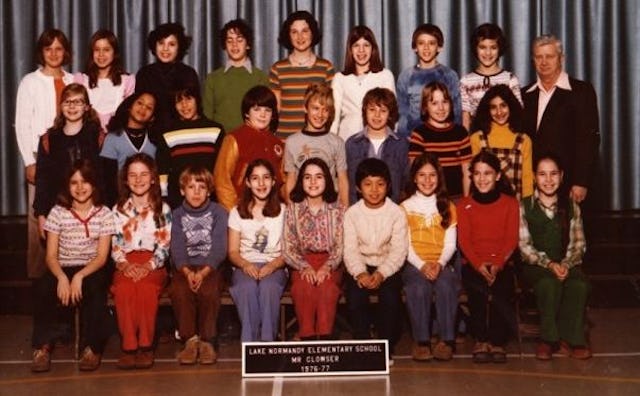

The arts were an integral part of our open classroom education, and many of my former classmates from Lake Normandy have flourished therein. In our sixth grade production of The Wiz, my then-boyfriend David Nevins was the Wiz to my Dorothy. Now he runs Showtime. I recently asked him if he, too, thought Lake Normandy was responsible for the person he’s become, and he agreed wholeheartedly. Nevins was a brilliant student, one of the smartest in our class, but he was also the typical Lake Normandy kid. Whenever our fifth-grade teacher Mr. Clowser would turn his back to write what we considered particularly long-winded or boring stuff on the chalkboard, David and his best friend Jerry Solomon, who now runs Persuade, would simply walk outside to play basketball.

What strikes me today, remembering my friends’ stolen layups, is how unremarkable it seemed to simply leave a classroom when you were bored. Whatever rules there were at Lake Normandy were actually made to be broken. “I do look back at Lake Normandy with fondness,” said Solomon, “not really for the experimental nature of the education but for the simplicity of the time. Or maybe it was just the freedom to cut class in 5th grade to play basketball without consequence.”

Authority, too, was meant to be questioned. Once on an oceanography test in Mr. Clowser’s class, I chose “none of the above” on a multiple-choice question about the cause of the bends and was marked incorrectly. The correct answer was supposedly “the formation of nitrogen bubbles.” I argued that it wasn’t just the formation of the nitrogen bubbles that caused the bends, but rather the rate and duration of the outgassing of these bubbles whenever the diver surfaced too quickly.

I ultimately was able to argue my case and get the point back. I also suggested that multiple choice questions might not have been the best way to test our knowledge of a rich subject such as oceanography. Mr. Clowser responded by making our next test open-ended. Yes, I was an annoying punk of a kid, and if you ask my children (or perhaps even my editors here) they’ll probably claim I’m an equally annoying punk of an adult today, but this early training in questioning authority has not only stayed with me, it’s also produced a small army of grown-ups who break boundaries and refuse to kowtow to the status quo. Browsing through Facebook profiles of other long-lost Lake Normandy pals, I see many graduates who are artists, musicians, writers, executives, and free thinkers in nearly every field. I don’t think this is a coincidence.

Last week, my youngest child, 8, had to sit through three days of New York state-mandated testing. This week he’ll have to sit through three more. The results of these tests will dictate both the future budgets for his school as well as the worth of his teachers. As I said goodbye to him each morning in front of his public school in Inwood, which is as non-traditional and arts-infused as you can get in New York City, I still felt a pang over what gets lost when we measure the value of an education by how adept our children are at filling in bubbles on a test, instead of by how much time and freedom we are giving them for studying how real bubbles form and watching them pop. Or for taking a teacher to task over a question about nitrogen bubbles. Or for sifting through one’s own random thought bubbles in the hopes of creating new connections that were not previously apparent.

Lake Normandy Elementary School shuttered its doors soon after my class graduated. The flower-shaped building still exists, but now it’s a recreation center. Or something. I’m not sure, and I don’t really want to know. When I visit my mom, I try to avoid driving past it. It’s too painful to imagine it as anything other than Arcadia.

This article was originally published on