We Need To Follow The Lead Of This Memphis Preschool

Perea Preschool in Memphis, Tennessee, is taking a wonderfully interesting approach to teaching children about nutrition by mixing fruit, vegetables, and play. Many of the children attending Perea Preschool come from impoverished families where, according to Atlantic Monthly, “Parents are making tough choices between a $1 head of lettuce and five boxes of macaroni and cheese.”

For some children, were it not for Perea Preschool, they would have very little exposure to fruits and vegetables. But naturally, like any parent of a preschooler, getting a child to eat something out of their comfort zone is difficult to say the least. Last week, I had a longer than I’d like to admit staring contest with my 7-year-old who refused to eat a stick of asparagus but insisted on getting a dessert. The gagging from my 9-year-old when he is encouraged to try something new is enough to keep me from ever trying that again.

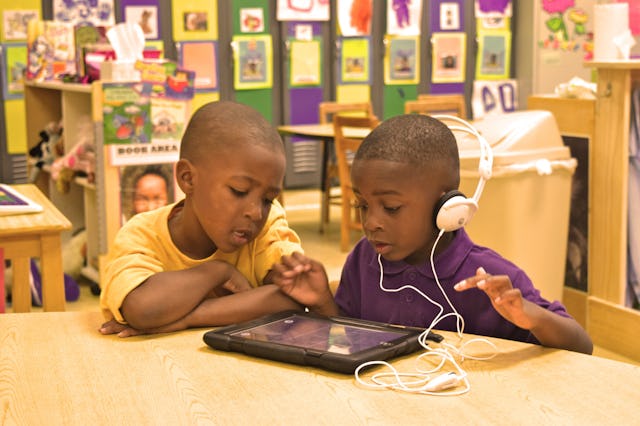

But the kind, patient, great educators at Perea Preschool are trying something different, and it seems to be working. The school is funded by a local health care organization, and nutrition is a key component of the curriculum. They are strong subscribers to the science behind nutrition and early brain development. And to get children to try those new foods that my kids so often stick their nose up at, they are incorporating them into play.

According to Vicki Sallis Murrell, a professor of counseling and educational psychology, “Play is the best way to influence behavior and teach lessons about health in early years.” Perea never introduces a food by having a cafeteria employee plop a scoop on a plate — there is always an explanation or exploration, Alicia Norman, the school’s principal, told Atlantic Monthly. “During a pumpkin-centered activity, children see a raw pumpkin before seeds are roasted or pies are made. They’re encouraged to stick their hands in and feel the texture of both the seeds and the pumpkin meat. If they want to try raw pumpkin, that natural curiosity is indulged.”

And some of you reading this might be asking, “How healthy is a pie?” Well, I suppose it depends on how you look at it. The idea behind all of this is to encourage children to see food as a process, as something that comes from something, and give them the opportunity to feel, explore, and play with fruits and vegetables before they are served to them. This grants children the chance to see where food comes from, become comfortable with it, and not assume that all food comes from a can or a package, but from actual plants. Kids are more likely to try something they feel comfortable with.

As a parent, I’d love to see more schools take this approach. My wife currently works in education, and she is in the process of building a garden program with a similar idea of mixing nutrition, education, and hands-on learning. Although it is targeted at junior high students, essentially, groups of young boys and girls will learn how to grow fruits and vegetables in the school’s garden and greenhouse.

They will learn about the nutritional value of the foods they are growing, along with the process of taking food from the earth, processing it, and distributing it. Then, once their plants are ready to harvest, the children wind out the school year by delivering the food they grew to the school cafeteria and so it can be served to themselves and their classmates. The hope is to help children gain a better understanding of the process from land to the table, and in doing so, help children learn how to eat better and not see food as some thing that magically comes from a store shelf or package pulled from the pantry.

Obviously, there are several ways for schools to approach nutrition education. Overall, the sad fact is, many American children are very disconnected from food production and ultimately are losing out. I’m in my mid-30s, and this wasn’t the case with my childhood. I was raised next to my grandfather’s farm. We had a large garden, and it wasn’t unusual for me to pull food from the ground and deliver it to my kitchen.

But now, kids don’t see much of that, and with that separation, children are obviously losing touch with what it means to make healthy food choices. The goal of many of these programs is to help students better understand nutrition, eat better, and develop to their full potential by getting the healthy food their bodies need. These programs are especially essential in impoverished areas and areas that are known as food deserts. Children in these areas are far less likely to have access and exposure to fresh foods or the ability to incorporate them into their family meals.

I believe I can speak for most parents when I say that I hope to see more schools follow the lead of Perea Preschool.

This article was originally published on