I Thought I Wasn't Racist Simply Because I Was Kind

It would be very easy for me to say I am not racist.

I would never in a million years use a racial slur. I have never said, “All Lives Matter,” and I fully understand why that statement is harmful and infuriating. Never in a million years would I mistreat a person based on the color of their skin. Some of the people I love and respect most in my life are black. I would not be the person I am today if not for my mentor throughout my teen years and her family.

I just spent a lot of years not understanding racism. At all. I remembering learning a little bit about the Civil War era and slavery in America, but nobody ever taught me what happened to slaves after slavery was abolished. My education consisted of a few quick lessons every February about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement, and it was presented as total victory. In my white mind, everything was equal. The work was done.

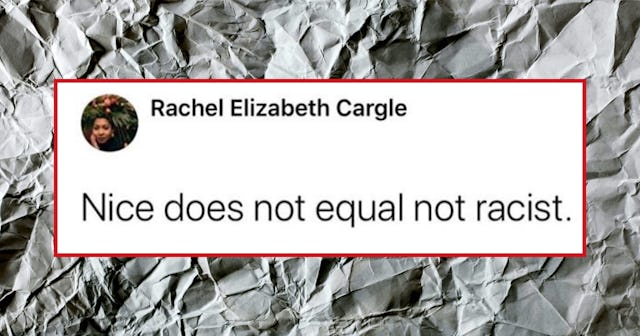

That’s pretty much all I ever knew. I understood racism to mean hating and hurting a person of another race because you feel inherently superior to them. That wasn’t me, so I couldn’t be racist, right?

I’ve always been kind, and that’s all anyone ever told me to be.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CA_4I2wHWiB/

It never occurred to me that I might hold racist, biased, harmful, dismissive ideas and opinions until a few years ago.

I was twenty-seven years old when Trayvon Martin was murdered. It was the first time I really chose to try to understand anything about racism outside of the dictionary definition. Until that point, the conversation about race was vague background noise to me. I wasn’t a target of racism, and I felt so sure that I wasn’t part of the problem, that I just didn’t feel any of it applied to me.

But the conversation surrounding Trayvon’s murder started me down a path of self-reflection that opened my eyes to so many of my own shortcomings. To be honest, although I’ve learned a lot in these eight years, I have remained mostly quiet. I’ve been listening to black voices when they explain their frustration, anger, trauma and pain. I have been trying my best to take in information about systemic racism, and how we ended up here.

But I haven’t spoken up very often. I thought it wasn’t my place.

I was so wrong.

George Floyd’s death has sparked possibly the loudest conversation about racism and police brutality that I have ever personally witnessed. This week, I have seen black influencers, scholars and citizens saying the same things over and over.

“White allies, speak up, but don’t speak over us. White silence is violence. Confront your biases. Stop being part of the problem.”

Maybe I have never intentionally been cruel to a person because of their race, but in more subtle ways, I have been guilty of racism and racial insensitivity.

Years ago, (before I knew the term microagression or understood how fawning all over black hair when it looks more like white hair sucks) my friend walked into my home with her usually curly hair straightened to glistening perfection. It fell down all around her in gorgeous, shiny sheets, and I was instantly drawn to it. Without her permission, I ran my fingers through the ends of it, exclaiming about how amazing it looked.

And it did look beautiful. It shined like a gemstone. But I had no idea in that moment how many times she had endured people she barely knew reaching out to touch her hair like it was public property, simply because it’s beautiful. I didn’t realize how often little black girls have to dodge curious hands from peers and adults alike. I just didn’t know.

But ignorance is not an excuse. I still caused discomfort and harm in that moment. It was white privilege that allowed me to “not know.”

I should have done better.

I have quoted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., cherry picking bumper-sticker-worthy ideas like, “I have decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear,” while totally ignoring the inconvenient parts of his message, such as, “Let us say boldly that if the violations of law by the white man in the slums over the years were calculated and compared with the law-breaking of a few days of riots, the hardened criminal would be the white man.”

When people have made racist jokes in my presence, I’ve sat by silent, nauseous and angry, feeling morally superior for not having made the joke myself, but never having the boldness to tell the overt racist to shut the hell up.

In the past, when people have pointed out to me the success of affluent, famous black people as “proof” that we all have the same opportunities, and “life is what you make it,” I have accepted that opinion as valid.

I’ve never felt inherently more important that anyone else based on their skin color. I have certainly never intentionally sought to hurt another human being because of their race. But that’s not all racism is. I haven’t been a hateful, despicable racist.

But I have been comfortable benefitting from the same systems that hurt the people I love.

It’s been a long time now since I was totally clueless. Sometimes, after you have learned to do better, it’s easy to forget that you still have a lot of work to do, and a lot of internal biases to tackle. But even though I’ve learned a lot, I still have so much more learning to do.

And it’s not optional. I have three white children. My role at this point could not be clearer. My kids have to grow up knowing more than I did, and my husband and I have to make sure that happens.

When I told my seven-year-old son about what’s going on in the world this week, he cried. Hard. He listed the black people that he knows and loves, and imagined if they were gone. He grieved at the idea that police officers were not all “good guys.” He said, “Eight minutes is such a long time for someone to hurt someone else, Mommy.”

My heart shattered. I don’t want to see him to hurt like that. I want to save him from this. For a few minutes, I considered not telling him about racism anymore for a few years, just to protect his little heart from pain.

But that’s just not an option. These conversations have to happen early and often. Black parents don’t have the luxury of protecting their children’s precious hearts for just a little while longer. It could mean leaving them unaware of the profound dangers they could face because of their skin.

Until all moms can choose innocence over hard truths, none of us can.

If I let my child grow up in blissful ignorance, he will become part of the problem. He will be one more white man who has never even considered that things aren’t equal. Even if he grows up to be smart and kind, arms and heart wide open to everyone, it’s not enough. You can be kind and still be part of the problem. I was.

I have never considered myself racist, but I have been racist anyway. Obviously, I can’t undo the past, but I can keep moving forward and doing better. Black lives depend on white people being better. There is no other choice.

This article was originally published on