My Later Abortion Of One Twin Saved Our Daughter's Life. This Is Our Story.

The introduction of state- and federal-level abortion restriction legislation, as well as the utterly false narrative of late-term abortions spun during the presidential debates last year, have ignited the pro/anti-choice debate again and sent lawmakers into a frenzy to introduce many restrictive measures. H.R.586, essentially a federal “personhood” and “heartbeat” bill, and Texas’s “wrongful birth” S.B.25 are just two of the federal- and state-level bills introduced to restrict abortions. I want you to know the faces of the issue. I am the issue. My husband is the issue. Our daughters are the issue.

We struggled to get pregnant. When other treatments failed, we decided to travel from our home in Texas to the Czech Republic to use donor eggs. We transferred our only two embryos and later found we were having twin girls. We got to know them, and we loved them fiercely: our little diva, Olivia, and camera-shy cuddle bug, Catherine.

Darla Baker

I remember being anxious to get to and through our 20-week scan in June because, with twins, the 20-week mark is as safe as you can get in terms of miscarriage risks. Afterwards, the doctor took over an hour to come in. He asked me to sit down next to my husband before telling us that Catherine had a number of issues.

The encephalocele (a neural tube defect) was the most dire. They occur in about 1 in 13,000 live births each year, and only 1 in 5 babies diagnosed with an encephalocele in utero survive to delivery. She was a couple of weeks behind in growth, had a large cleft lip/palate that was making it impossible for her to swallow amniotic fluid and regulate her sac size, and showed signs of fused digits.

Our obstetrician told us if she made it through delivery, she would suffer greatly. He referred us to a specialist, the only one in town he knew of who would perform the unthinkable, should we need it.

That specialist called us directly that evening. He wanted to do his own imaging but described her prognosis as “grim.” That weekend is a blur, but I know we cried and did everything we could to distract ourselves. That scan confirmed the OB’s suspicions, plus we were told her cerebellum was underdeveloped and that her sac was growing too much, putting Olivia in danger.

We opted for an amniocentesis, but while we waited for those results, we visited another specialist in Houston. He confirmed previous findings, labeled her small head size “microcephaly,” had trouble even finding her cerebellum, and noted that the midline of her brain was shifted, indicating “severe disorganization,” a phrase that will stick with me forever. The cleft was the width of an adult pinkie finger. The encephalocele was open and brain matter was being leached out.

Our doctors counseled us throughout the ordeal. If we carried to term, we would likely deliver early. If Catherine survived delivery, she would face a barrage of surgeries, starting with removing the encephalocele and placing her brain tissue back inside her skull. She would be severely disabled if she wasn’t a vegetable. And we didn’t know what an early delivery would mean for Olivia.

Our other option was to terminate half of the pregnancy. Catherine’s death would likely mean a safe and healthy remaining pregnancy with Olivia.

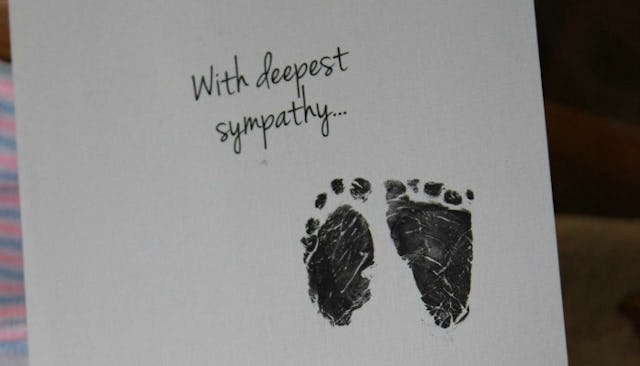

On June 22, we saw and heard Cate one last time — she danced for us. And then the doctor injected a medication into Cate’s heart. When they checked for a heartbeat 30 minutes later, the silence was deafening. When they found Olivia’s strong beating heart, we cried for her survival and for Cate’s loss, our loss, Olivia’s loss.

We took our daughter’s pain and suffering upon ourselves. She passed away peacefully, feeling my love and hearing my heartbeat. This wasn’t a choice of convenience, and she wasn’t unwanted. It will always hurt that we can’t have her. But Olivia was wanted too. And we believe that quality of life is just as important as a beating heart.

Darla Baker

Ours is the story of late-term abortion. We are the issue that you debate without having been there. Our daughters’ lives are the lives you claim to value even though Cate wouldn’t have had a life, and Olivia might not have either. Ours are the children you would rather have seen both die needlessly because “abortion is murder.”

I hope, reading this, that you will stop and think about what you’re supporting. Texas law meant we only had 12 days to decide. Waiting even one more day meant we would have to leave the state to do the compassionate thing for our children and begin grieving in a hotel room. Doctors can be wrong; miracles can happen. That’s why we got second and third opinions. We ran tests. None of our doctors had seen this combination of issues. It was one in a million — almost literally.

I ask for compassion for all the families who shoulder this burden for the rest of eternity. Never think that we went into this with eyes closed or made our decision lightly. I promise you we did not.

This article was originally published on