My Kids Have Sperm Donor Siblings, And This Is What That's Like

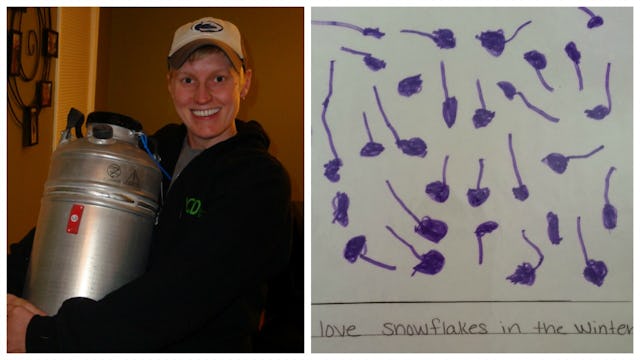

When my oldest daughter, who is now 7, was in preschool, she came home with a drawing of snowflakes. Except they didn’t look like snowflakes so much. They looked like the sperm in the children’s books we had been reading about how babies are made.

My partner and I started to talk to our first child about her sperm donor when she was 2 years old. I was more eager to start the conversation than my partner, but as the non-biological parent, I wanted this to be an early part of her narrative, and I wanted to be the one to share it with her. I can’t share her genes, but I can share her story. The conversation was pretty straightforward.

Using the book What Makes A Baby, I explained that you need a sperm and an egg to make a baby. Before I continue, I would like to point out that this is the recipe for all pregnancies. Sperm banks are not just for lesbians or two-uterus couples. Single—both queer and straight—women, trans men, and heterosexual cisgender couples also make families using donor sperms. Making babies is about fertility, not sexuality.

When talking to my daughter about this, I stuck to the science not the logistics. I didn’t get into all of the different ways sperm and egg can meet, but she knows she was made with her mama’s egg and sperm from a donor. She knows she grew in Mama’s belly and in my heart. As she got older we used Zak’s Safari to help explain who a sperm donor is and what characteristics and genetics he contributed to her creation. I used these books to talk to my twins, age 5, about how they were made too. But before they were even officially introduced to those details, they were aware of their story. Their big sister made sure of it.

The sperm needed to create my family, to create my kids, was very expensive. And I get why it had to be so expensive—background and health screenings and storage and insurance and blah, blah, blah—but for how often that shit is wasted in tissues and other places I hate to imagine, it hurt to pay $6,000 for sperm. And that was 10 years ago. That stuff is not getting any cheaper, folks. But look for deals. If you buy enough vials at once, you can usually take advantage of free storage for a few years. You gotta spend money to save money, even when you are spending it on semen.

But the peace of mind of getting quality sperm from a reputable place made it worth it.

The more surprising part is that the extended family we acquired through this process made it worth every penny too. In addition to celebrity look-a-like photos, personality profiles, essay questions and answers, voice analysis, and about 20 other features to get to know your donor, the cryobank has a sibling registry. This is a place where people who used the same donor can connect via the donor’s unique ID number. Families can leave contact information in hopes of getting to know the parent(s) of their children’s half siblings; siblings have a way to grow up together or at least get to know each other.

To be honest, I was resistant to all of this. Picking a sperm donor was hard for me. Choosing a creative man with blonde hair and blue eyes reminded me that if my kids had these traits, they would not be from me. I could choose a donor who resembled me in looks and personality, but I would not contribute to their biological creation. And in many places, as a partner in a same-sex relationship, that means I don’t have any parental rights either. Needing a third party to create the baby I wanted felt invasive. And inviting other families and their kids—strangers who share more DNA with my child than I ever will—felt threatening.

But it was never the sperm donor who invaded my space; it was doubt that I could feel a connection to my child. Her first cry filled me with love I had never known. Her blue eyes mirror mine in a way that tells me she is mine. If I stop to consider how I became a parent, the gratitude I have for the man who created my first child and her siblings overwhelms me.

And the threat of jealousy or insecurity I had before meeting my kids’ donor siblings and their parents seems really silly now. When my oldest daughter was a few months old, my partner signed us up for the sibling registry. There was already another couple listed who shared the same donor as our daughter. They had twins who were a couple of months younger than our daughter. We exchanged a few emails and photos. Hesitation turned into curiosity into fondness into affection and love. The oldest three kids met when they were all around 18 months old. Their siblings—twins on our end and a singleton on theirs—completed the six pack of donor siblings.

Contrary to my prior feelings, these people didn’t take anything away from me or my relationships with my children; they added pieces to our family’s puzzle. All of the kids will proudly tell you about their brothers and sisters who live in a different state; they burst with anticipation and excitement for family vacations, video messages, and packages in the mail. We spend holidays together. The six kids adore one another, but they fight and compete too. It’s not all rainbows and unicorns when we are together. There is jealousy and anger too. But that comes with the comfort and safety they have with each other. They are siblings through and through and that means shoving matches as well as sweet moments of affection.

While they are all close, their personality traits and likes and dislikes have allowed some of the siblings to form tighter bonds than others. My oldest is closer with the sister who lives out of state than with the full sibling who lives with her. This is partially because of age—my daughter and her donor sister are only a few months apart —but it is also a sister thing. They have a special connection that was created in large part by the donor. Each relationship between the siblings is unique and it has been fun to watch the dynamics shift and strengthen as we spend more time together. It gets a bit harder with each visit though because as they get older, they get closer and saying goodbye hurts.

But that’s the thing about love. It intimidates and hurts us. But it also surprises and completes us. Sometimes love looks scary. And sometimes it looks like a child’s interpretation of snow.

This article was originally published on