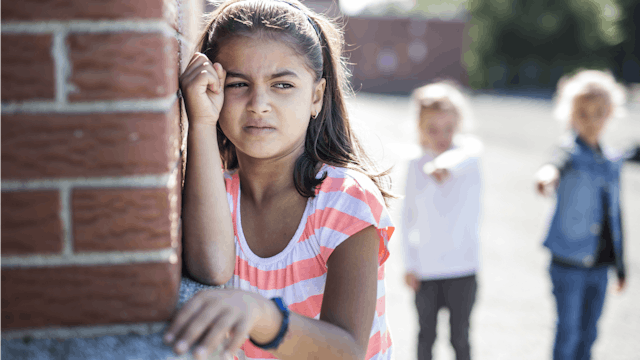

Is It Rude, Is It Mean, Or Is It Bullying?

A few weeks ago, I had the terrific fortune of getting to present some of the bullying prevention work that I do to a group of children at a local bookstore. As if interacting with smiling, exuberant young people was not gift enough, a reporter also attended the event a wrote a lovely article about my book and the work I do with kids, parents, educators, and youth care professionals. All in all, it was dream publicity, and since then, it has sparked many conversations with people in my town who saw my photo in the newspaper and immediately related to the examples of bullying that were discussed.

I have been brought to tears more than once since the article ran, while listening to parents share their feelings of outrage and helplessness over their kids’ experiences with bullying in school. One gifted, but socially awkward middle school student blew me away with his articulate, poised, yet searingly painful accounts of relentless physical and verbal bullying on his school bus. An elementary school-aged girl described how she had to learn to shed her Australian accent within a month of entering U.S. schools because of how she was shunned by her classmates. The commonness of it all routinely astounds me with every new account; the pervasive cruelty makes my jaw drop every time.

It is important for me to begin this article by establishing that without doubt, many of the stories of bullying that are shared with me are horrifying, and some are unspeakably cruel. But now, I also want to be honest and share that some of the stories are, well, really not so bad.

Take this story recently shared with me by an acquaintance who read about my professional work:

“Signe, I saw your picture in the paper last week. Congratulations! I didn’t know you worked with bullied students. It’s so important that you do—things have gotten so bad! Last week, my daughter was bullied really badly after school! She was getting off of her bus when this kid from our neighborhood threw a fist-full of leaves right in her face! When she got home, she still had leaves in the hood of her coat. It’s just awful! I don’t know what to do about these bullies.”

“Was she very upset when she got home?” I empathized.

“No. She just brushed the leaves off and told me they were having fun together,” she said.

“Oh,” I answered knowingly, aware that oftentimes kids try to downplay victimization by bullies from their parents, due to the embarrassment and shame they feel. “Did you get the sense she was covering for the boy?”

“No, no. She really seemed to think it was fun. She said that she threw leaves back at him, which I told her NEVER to do again! The nerve of those kids.”

“Those ‘kids,’ I clarified. “Was it just the one boy throwing leaves or were there a bunch of kids all ganging up on her?”

“No, it was just this one boy that lives about a block from us,” she assured me.

“Is he usually mean to her? Has he bothered her after school before?” I asked, eager at this point to figure out what the bullying issue was.

“No. I don’t think so at least. That was the first time she ever said anything about him. It was definitely the first time that I noticed the leaves all over her coat. But it better be the last time! I won’t stand for her being bullied by that kid. Next time, I am going to make sure the principal knows what is going on after school lets out!”

While I always want to be careful not to minimize anyone’s experience (it’s the social worker in me!) and a part of me suspects that the sharing of this particular story may have been simply this parent’s spontaneous way of making conversation with me in a store aisle, I hear these “alarming” (read: benign) stories often enough to conclude that there is a real need to draw a distinction between behavior that is rude, behavior that is mean, and behavior that is characteristic of bullying. I first heard best-selling children’s author, Trudy Ludwig, talk about these distinguishing terms and, finding them so helpful, have gone on to use them as follows:

Rude is inadvertently saying or doing something that hurts someone else.

A particular relative of mine (whose name it would be rude of me to mention) often looks my curly red hair up and down before inquiring in a sweet tone, “Have you ever thought about coloring your hair?” or “I think you look so much more sophisticated when you straighten your hair, Signe.” This doting family member thinks she is helping me. The rest of the people in the room cringe at her boldness, and I am left to wonder if being a brunette would suit me. Her comments can sting, but remembering that they come from a place of love — in her mind — helps me to remember what to do with the advice.

From kids, rudeness might look more like burping in someone’s face, jumping ahead in line, bragging about achieving the highest grade, or even throwing a crushed up pile of leaves in someone’s face. On their own, any of these behaviors could appear as elements of bullying, but when looked at in context, incidents of rudeness are usually spontaneous, unplanned inconsideration, based on thoughtlessness, poor manners, or narcissism, but not meant to actually hurt someone.

Mean is purposefully saying or doing something to hurt someone once (or maybe twice).

The main distinction between “rude” and “mean” behavior has to do with intention; while rudeness is often unintentional, mean behavior very much aims to hurt or depreciate someone. Kids are mean to each other when they criticize clothing, appearance, intelligence, coolness, or just about anything else they can find to denigrate. Meanness also sounds like words spoken in anger — impulsive cruelty that is often regretted in short order. Very often, mean behavior in kids is motivated by angry feelings and/or the misguided goal of propping themselves up in comparison to the person they are putting down. Commonly, meanness in kids sounds an awful lot like:

– “Are you seriously wearing that sweater again? Didn’t you just wear it, like, last week? Get a life.”

– “You are so fat/ugly/stupid/gay.” – “I hate you!”

Make no mistake — mean behaviors can wound deeply, and adults can make a huge difference in the lives of young people when they hold kids accountable for being mean. Yet meanness is different from bullying in important ways that should be understood and differentiated when it comes to intervention.

Bullying is intentionally aggressive behavior, repeated over time, that involves an imbalance of power.

Experts agree that bullying entails three key elements: an intent to harm, a power imbalance, and repeated acts or threats of aggressive behavior. Kids who bully say or do something intentionally hurtful to others and they keep doing it, with no sense of regret or remorse — even when targets of bullying show or express their hurt or tell the aggressors to stop.

Bullying may be physical, verbal, relational, or carried out via technology:

– Physical aggression was once the gold standard of bullying — the “sticks and stones” that made adults in charge stand up and take notice. This kind of bullying includes hitting, punching, kicking, spitting, tripping, hair-pulling, slamming a child into a locker, and a range of other behaviors that involve physical aggression.

– Verbal aggression is what our parents used to advise us to “just ignore.” We now know that despite the old adage, words and threats can, indeed, hurt and can even cause profound, lasting harm.

– Relational aggression is a form of bullying in which kids use their friendship — or the threat of taking their friendship away — to hurt someone. Social exclusion, shunning, hazing, and spreading rumors are all forms of this pervasive type of bullying that can be especially beguiling and crushing to kids.

– Cyberbullying is a specific form of bullying that involves technology. According to the Cyberbullying Research Center, it is the “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices.” Notably, the likelihood of repeated harm is especially high with cyberbullying because electronic messages can be accessed by multiple parties, resulting in repeated exposure and repeated harm.

So, why is it so important to make the distinction between rude, mean, and bullying? Can’t I just let parents share with me stories about their kids?

Here’s the thing: In our culture of 24/7 news cycles and social media sound bytes, we have a better opportunity than ever before to bring attention to important issues. In the last few years, Americans have collectively paid attention to the issue of bullying like never before; millions of school children have been given a voice, 49 states in the U.S. have passed anti-bullying legislation, and thousands of adults have been trained in important strategies to keep kids safe and dignified in schools and communities. These are significant achievements.

At the same time, however, I have already begun to see that gratuitous references to bullying are creating a bit of a “little boy who cried wolf” phenomenon. In other words, if kids and parents improperly classify rudeness and mean behavior as bullying — whether to simply make conversation or to bring attention to their short-term discomfort — we all run the risk of becoming so sick and tired of hearing the word that this actual life-and-death issue among young people loses its urgency as quickly as it rose to prominence.

It is important to distinguish between rude, mean, and bullying so that teachers, school administrators, police, youth workers, parents, and kids all know what to pay attention to and when to intervene. As we have heard too often in the news, a child’s life may depend on a non-jaded adult’s ability to discern between rudeness at the bus stop and life-altering bullying.

This post originally appeared on Psychology Today.