U.N.I.T.Y. Why Intersectionality Is Important In This Post-Election World

As I sat watching the CNN docu-series The Seventies episode focusing on feminism, I realized something: The landscape of feminism back then was overwhelmingly white. When I started digging and doing more research, I realized that the landscape of feminism has always been overwhelmingly white. Watching the archival footage of women like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan made me wonder, What about Angela Davis? Where’s Audre Lorde? Why weren’t they being given a seat at the table?

As a black woman, it forced me to examine modern feminism to see if women of color, and especially black women like me, were still being excluded from the conversation. I had always hesitated labeling myself a feminist. I originally thought it was because of the negative connotation of the word societally, but when I dug deeper, I realized that it was because it felt like a term that couldn’t apply to me.

The feminism that I was being fed, that many of us are fed, is a very one-sided (white) view of feminism, and it is something I just can’t support. This glaring disparity was never more real to me as it was during this election, and the months that have followed. It is under these circumstances that I have examined feminism and the desperate need for intersectionality within it.

Intersectionality is a word that you have surely heard being thrown around a lot since August of 2016 when Hillary Clinton officially accepted the Democratic nomination for president. The concept has always been there, but the term was officially coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, a black civil rights advocate. It studies how intersecting identities (race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, etc.) work within the structures of oppression and discrimination.

But in the face of the very white narrative that was being painted by Clinton and many of her supporters, women of color, queer women, women “othered” by the white female narrative being portrayed, began to rally for their proper seat at the table. In 2016, when being “other” is fast becoming the majority, it is impossible to promote feminism without these voices.

When the Twitter hashtag #ImWithHer popped up in support to Clinton, black women (and by extension many other women of color) countered with the hashtag #GirlIGuessImWithHer. I immediately attached to the new hashtag, and used it in everyday conversation. Why? Why would we women of color be reluctant to join the fold?

Well, Hillary Clinton and her peers were some of those same early feminists who didn’t give us black women a seat at the table back then and were still falling short this time around when our voices would have been most useful. Instead, Clinton pandered to our basest interests by claiming that she “carried hot sauce in her purse.”

On election day, when Clinton supporters told everyone to wear white to the polls for the suffragettes, they were spreading the martyrdom of white supremacy. The suffragettes wore white to drive home the point that only white women deserved the right to vote. They thought that they (white women) were far more intelligent and worth protecting more than black men. So on election day, instead of posting solidarity posts, I posted the racist quotes from these women to show my friends that in holding these women up as tenets, they were only further spreading the damaging ideology of white supremacy.

When it was revealed post-election that white women overwhelmingly voted against Hillary Clinton, I wasn’t surprised at all. White women were voting to protect themselves and their interests, which is a throwback right to those suffragettes who were being so heavily revered. When it came out that 94% of black women voted for Clinton, however reluctantly, it only confirmed the fact that we were truly the ones fighting to protect more than just ourselves.

In the days post-election, a friend added me to the now infamous Facebook group Pantsuit Nation. I really didn’t have much interest in the group after poking around and discovering that many stories followed the trope about how a white person protected a more marginalized person because they felt compelled by the whole safety pin movement. And they needed to share this story publicly for head pats and high fives. The white savior narrative is so old. When I learned that the group had repeatedly silenced marginalized voices in favor of these narratives, I had to go.

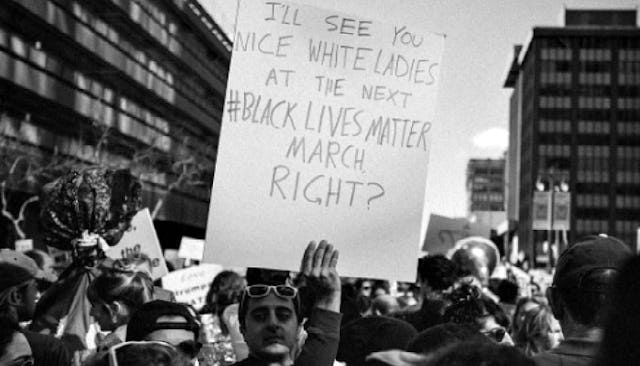

Then I began to hear rumblings of the Million Women’s March, which sounded eerily similar to the Million Man March which was exclusively for black men to come together. My father, who is a member of the Nation of Islam, told me that the Nation was thinking of pursuing legal action to stop the use of the name for the march, especially since the board of the Women’s March was — surprise, surprise — white. These women were modern-day suffragettes, only coming together to fight injustice because now their rights were being compromised, but not letting those whose rights were always compromised join the dialogue, even though they have much more to offer.

This is why intersectionality is absolutely crucial to the dialogue of feminism: One group of women with one singular experience cannot speak to the experience of all women.

White women have notoriously made feminism “theirs,” and those who try to offer an alternative perspective are written off as “divisive.” We are not being divisive; we are fighting simply to be heard. A cursory Google search of prominent feminists leads to lists that are predominantly and overwhelmingly white, the only women of color who are mentioned are mainstream black women like Oprah and Maya Angelou.

When we drop the names of celebrities like Lena Dunham and Emma Watson into the feminist conversation, where are their black equivalents like Jessica Williams, America Ferrera, or Yara Shahidi? When the table can literally be as big as we want it, why is it that only white women get an invitation and a gold-plated seat? Why are women of color seen as “divisive” when we bring up our struggles as women of color? Why are we silenced and dismissed and branded as troublemakers and problematic? We are not trying to play “Oppression Olympics” with you. We are simply telling you like it is. This is our life. These are our experiences.

When we speak, instead of shutting us down when we say something that is uncomfortable for you to hear, how about you shut up? Just shut up, and listen. We’re not looking for sympathy; we’re looking for acknowledgement and understanding. If you’re a white cisgender, heterosexual female and your friend who is not all of those things comes to you and expresses a concern, just stop talking and LISTEN. Don’t say, “I’m so sorry,” say “I hear your concerns, and I will do whatever I have in my power to help you.” Acknowledge your privilege. Rest assured, we aren’t looking to co-opt the way of life of White America. No, thank you. We simply want our chance to have what we have been led to believe we deserve as Americans.

And we are still waiting.

This article was originally published on