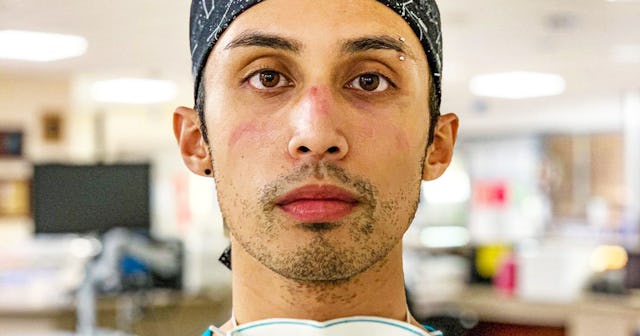

'I'm Not A Hero, And I'm Not Ready To Die'––NYC Nurse Gets Candid About COVID-19

Yesterday, I considered writing a will.

I am 24 years old. I am an ICU nurse in New York City. I am in good health at this time, so I should have no reason to even think about writing a will. But yesterday, I resigned myself to the fact that my likelihood of dying is statistically more plausible than I had previously imagined.

When I graduated from my nursing program in 2018, I never thought this would be my future with barely two years in the field. I thought I was prepared to see death; I had seen enough of it within my first year in the ICU. Yet, in the last two weeks, I have seen more people die than most people see in their entire lives. Now, I am not so sure if death is something I am prepared to see anymore.

Death is different now. Death could pick me.

Last week, a daughter called asking about her mother. She thought her mother’s condition was stable. I realized no one had updated her; things are vastly different now that family is not allowed in the hospital. So, I reluctantly but gently told her that if I stopped the IV pump right now, her mother would die. I had to be blunt — why lie or sugarcoat what is happening? Uncontrollably and expectedly, she began to weep.

I have auscultated the sounds of a dying heart. But, never before have I heard a dying heart through the phone.

And, I stood there awkwardly clutching everything I needed before entering the room, hoping I didn’t forget anything while she was sobbing on the phone: medications, tubes, vials, needles, syringes…my mind races through what I need to do while also attempting to listen to what she might have to say.

Every time you go into a COVID patient’s room, you expose yourself, so I tell myself, “Anything you forget that forces you to come back into the room is something that might kill you.” I struggle to focus on being human as I stand there in the middle of the hallway, unsure of what to say back, my mask half on and a trickle of sweat forming under the multiple layers of PPE.

How do you apologize for not being enough?

I have been told I am on the frontline, but the truth is, I am the final recourse. I am one of the few who are the last people you want to see, because after us is death. Outside of the pandemic, the ratio in the ICU is two patients to one nurse, maximum. Now, the expectation is three patients to one nurse. In other ICUs and in other hospitals, particularly those in the outer boroughs, that ratio is even higher. I am privileged to have just three patients some days.

Those days break me.

Courtesy of KP Mendoza

ICU nurses are trained to be precise: we medicate, we titrate, we sedate, we paralyze, we help intubate. We wash your body, clothe you, feed you, and make you comfortable. We enter that room more than anyone else. People have lauded me as a hero, a superhero to some, an angel even — that I am brave and courageous, that my patients are lucky to have me. Most days, I feel far from that.

Now more than ever, I feel weak and inept. I am lucky if I even have time to put ointment on your chapped lips as you lay comatose, moments before I FaceTime your family and they see you for the first time since leaving for the hospital, breathing tube now in your mouth, feeding tube plunging into your nose, a slight drool, and maybe some blood here and there that I just can’t seem to stifle. And who am I to steal that sacred moment away from you and your family? Who am I to be privy to the sanctity of that final reunion? It feels like a sin. I am ashamed.

But I stand there nonetheless, stricken with shame and bereft of energy, because I am the only link you have to your family in this moment.

Sometimes, I get so busy that patients lie in their own stool longer than I would like to admit. How do you find time to clean your patient when your other patient’s heart rate just reached zero next door?

Even when I leave the hospital, I can’t escape this plague. The coronavirus follows me home literally and metaphorically. It’s on the soles of my shoes, on my clothes as I strip bare at the door, and on my hands as I scrub them red and raw to rid myself of the feelings of filth and decay. It’s in the sirens I hear outside wondering if that’s the next victim of this virus, in the ping of a text from a coworker who is informing me that our colleague’s father just died from COVID-19, and it’s in the ventilator alarms that go off in my mind even when my apartment is desolately silent.

Until now, I never knew the scourge of isolating alone; how the sound of silence could be so deafening.

On my off days, I spend hours reading articles, new studies released about side effects of this repurposed medication, benefits of this new trial; the plethora of information is interminable and overwhelming. Yet every day, I walk in to work feeling like I still don’t know enough about this disease, and every day, I leave work feeling like I failed, like I could have done so much more. It never feels like enough. I don’t feel like I am nearly enough.

That is why I tell people to not call me a hero. To me, it feels like a lie. I am a disgrace.

I wear guilt like a body wears a shroud. I run around for twelve hours a day, sometimes more if it was particularly busy that shift. Nowadays, I consider myself lucky if I have time to eat, blessed if I have time to pee more than once a shift. I conflate my blessings with my luck; I don’t know what to be thankful for anymore — the fact that I was able to eat a full meal unhurried or the fact that it isn’t me on that ICU bed right now.

I want people to know that this is beyond difficult. This isn’t the world of healthcare I expected to enter; none of us did. I studied to save lives. I signed up to care for the sick and dying, and yes, I acknowledge that this is all at the risk of my own health. But, do not misconstrue my choice of profession for a diminished sense of self-worth; I did not sign up to die.

I want the country to know that if I end up on that ICU bed, it is because I was not given a hazmat suit or enough PPE to protect me. I want the country to know that America has failed its people, most especially those it deems “essential” — that, I truly believe.

We claim to be the best, the freest, the richest country in the world — that no one else compares to our liberties. So, why is it that when my shift ends, I peel off the same N-95 mask that I have worn for 12+ hours straight? I have breathed in stale air all day on a unit rife with the dying, and at the end of those twelve hours, I flinch and scour my unprotected neck with a bleach wipe, hoping that the thin, easily torn, permeable yellow gown I wear as “protection” did just enough to stop the virus from seeping into my scrubs and settling under my skin.

Until there is a cure or a treatment, people will continue to die indiscriminately from this disease. Even after social isolation measures are lifted, everyone will still be at risk. Even after a peak, there will still be a plateau and a downhill journey, and people will continue to die even as we flatten the curve. For a long, long time, the ICUs will still be overwhelmed and the Emergency Departments filled beyond capacity. I want people to know that healthcare in America is broken. We did not prepare enough; New York is a sore example of that.

I believe this pandemic is so poignantly and painfully demonstrating the faults of our system.

When I was in college, I used to tell myself I was too busy to call my parents. At best, I’d call them once a week, maybe once a month if I was in the midst of midterms or finals. They’re immigrants from the Philippines who still work as nurses back home in Chicago. I even used to attribute my inability of connecting with them due to my hectic schedule and their unconventional shift times. But, it’s strange how anxiety claws at you. I read their stories in the medical histories over morning report; I see their faces in my dying patients — hear their children’s distraught voices pleading for updates, praying for good news. Was it their voice I heard, or was that mine over the phone?

I wonder if my parents have finally figured out why I frantically call them almost every night now.

I am still so young. I have dreams, and I hope to have a full life ahead of me. I want to go home to my mom and dad and their home-cooked meals. I want to see my four-year-old nephew grow up. I want to get married to someone with whom I can grow and love. I want to have kids, and I want my parents to spoil their grandkids like they did me.

So, I ask that you do not pity me, that you do not call me a hero. I do not wish to be made into a martyr. All I ask is that, after all this is over, that you never forget what it was like to be trapped in your home under quarantine. I ask you to never forget the morgue ice trucks, the absurd lack of toilet paper, and the frantic scramble for masks. I want you to remember the fear that gripped your body when someone coughed beside you or when you got that phone call from your loved one saying they had spiked a fever.

Clap for me and other healthcare workers at seven o’clock if it makes this pandemic feel more bearable. I concede, your cheers help us trudge on. Just know that cheers and hollering don’t change the outcome. This is my fervent plea — that we change what we can after all this is over.

This should never happen again.

Editor’s note: You can follow KP Mendoza’s journey here.

This article was originally published on