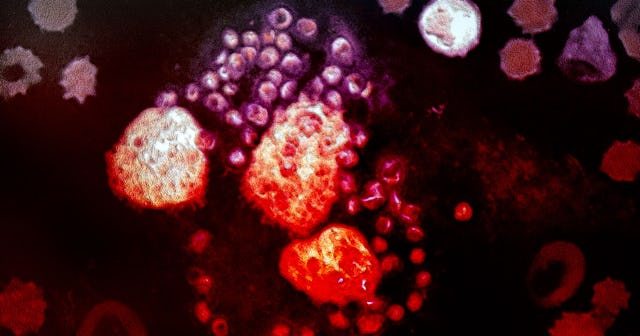

The Stuff Of Nightmares: Flesh-Eating Parasites Are Becoming More Common

I hate to be the bearer of bad news or be one of those people who sounds the alarm for no real reason, but uhhh, apparently flesh-eating parasites are becoming a thing now. Like, thanks to the earth heating up, they’re becoming more and more common because they’re surviving in places they couldn’t before and you know what? I am not okay with that. As if I needed more reasons to hate the outside or avoid beaches and far-flung destinations, a flesh-eating parasite known as Leishmania has migrated north from South America into the U.S.

Leishmania is by no means the only flesh-eating parasite we should be aware of (waves hi to flesh-eating bacteria Vibrio vulnificus and brain-eating amoeba Naegleria fowleri), and the fact that I had to type that sentence at all is extremely upsetting. Read on for the quick and dirty about what you need to know about these flesh-eating parasites and how you can keep yourself safe.

What are flesh-eating parasites?

I don’t mean to be glib, but it’s pretty self-explanatory, right?

In the case of Leishmania, it’s a protozoa, a one-celled organism similar to bacteria but bigger (sobs). Since they have a nucleus and other cell structures, they’re technically more like plant and animal cells than bacteria. But WHATEVER. It eats. Your. Flesh. Does it really matter?

The more than 20 species of Leishmania (cue more horrified screeching) cause a flesh-eating skin disease known as cutaneous leishmaniasis. Generally, sand flies feed on animals who have already been infected by Leishmania and become unwitting hosts to the parasites. It is then spread to humans via sand fly bites and can cause skin sores and possible organ damage. These sand flies flourish in rural areas and hot sandy beaches — and the parasite has been reported in Texas, Oklahoma, and Florida (of course).

While some strains of Leishmania are life-threatening, the one making its way across the U.S., Leishmania mexicana, causes milder symptoms and can heal on its own over time (usually years — and can leave scars). The most dangerous strains (e.g.: infantum and donovani) not only infect your skin, they can lead to death after infecting your liver, spleen, or bone marrow.

The brain-eating amoeba Naegleria fowleri is also a protozoa and is extremely fast-acting and difficult to treat after diagnosis. It causes a form of meningitis once the parasite enters your brain — but by the time you show symptoms, it’s usually too late. This is nightmare fuel, folks.

People are typically infected when swimming or diving in warm (76°F or warmer) freshwater rivers and lakes by entering the body through the nose and into the brain. You can’t get it from drinking, water vapor, or mist (thank goodness for small mercies), but it can enter your brain if you submerge yourself in contaminated water — say, swimming in inadequately chlorinated swimming pools or using a Neti pot with contaminated tap water.

As for flesh-eating bacteria Vibrio vulnificus, it is one species of a dozen Vibrio bacteria (like why are there so many kinds of these things?) and generally causes diarrhea in most people when they eat raw or undercooked shellfish like oysters. The other most common means of infection is when people swim in contaminated water with open wounds. In rare instances, an infection can lead to necrotizing fasciitis, a fancy term for when the tissue around the wound will die. Though it can rapidly destroy tissue, if diagnosed early enough, the disease can be treated with antibiotics.

Why are flesh-eating parasites expanding to other areas?

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty

So, why are all these flesh-eating parasites coming up north? Well, short answer: climate change.

Warmer waters

Since these parasites thrive in warmer waters, as the earth warms, it’s logical that they start expanding into other regions. Even as far back as in a 2010 National Library of Medicine paper, the study stated “…Climate change is increasingly being implicated in species’ range shifts throughout the world, including those of important vector and reservoir species for infectious diseases.”

According to that same report, the researchers predicted that rodents and flies carrying Leishmania would traverse to Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri by 2020 and that by 2080, an estimated 27 million Americans and Canadians would be exposed to leishmaniasis.

According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) there were only 34 deaths due to the brain-eating amoeba (it really hurts to write this repeatedly) from 2010 to 2019 in the U.S. However, though Naegleria fowleri infections used to be rare in North America because waters were generally too cold to host it, thanks to climate change, over the last decade, more and more cases have been diagnosed in southern states like Texas and Florida (here they are again!) and as far north as Minnesota and Maryland.

Increased brackish waters

As for Vibrio vulnificus, it flourishes in brackish or salt waters and as climate change incurs more frequent as well as stronger hurricanes, it also forces more salt and fresh waters to mix, thus creating large brackish areas and conditions ideal for Vibrio. Additionally, as a result of extreme flooding, the overflow water can expedite the spread of pathogens.

Drought conditions

In the West, drought conditions cause water reservoirs to condense as water evaporates and isn’t replenished. This increases the concentration of pathogens in the water supply and ups the odds of a person becoming infected through the municipal water distribution.

Shrinking wild spaces

While the ever-shrinking wild spaces is not technically part of climate change, it is also another reason why these types of pathogens are expanding their habitats and range. As forests and savannas are developed and cleared, the animals are forced to migrate as well as possibly have more human contact, increasing the likelihood for diseases to jump into the human population.

What can we do?

On an individual level, of course we cannot affect climate change in any meaningful way. Like all systemic changes, it’s a combination of changing laws, beliefs, and exerting pressure on large corporations and businesses. However, on a local level, as flesh-eating parasites like Leishmania become endemic in the U.S., it would be prudent for us to familiarize ourselves (and our medical professionals) with the signs and symptoms of leishmaniasis.

Though approximately 1.5 to 2 million people worldwide contract leishmaniasis and about 70,000 die from it every year, most of its victims are from poor, rural areas. Though expensive drugs are available to cure the more deadly strains, the disease hasn’t received much attention because the main affected people are poor.

The worry is that doctors will either not properly diagnose the disease or over treat it when they do. There have been other treatments developed such as applying liquid nitrogen to lesions or using local traditions such as those found among Mexican Mayan healers who have been dealing with the illness for thousands of years. There is also a promising vaccine in the works.

While this is good news, scientists say this is just the vanguard as vector-born (when diseases are transmitted between animals and humans by a living organism) and insect-borne diseases are expected to increase due to global warming. As Illinois-based dermatologist Bridget McIlwee told NPR that climate change pushes the species carrying the pathogens further north, “leishmaniasis is just one of a number of different diseases that we’re going to see more of.”

If that’s not further reason for me to never leave my house, I don’t know what is.

This article was originally published on