Beloved Nickelodeon Star Opens Up About Sharing Love Through Food

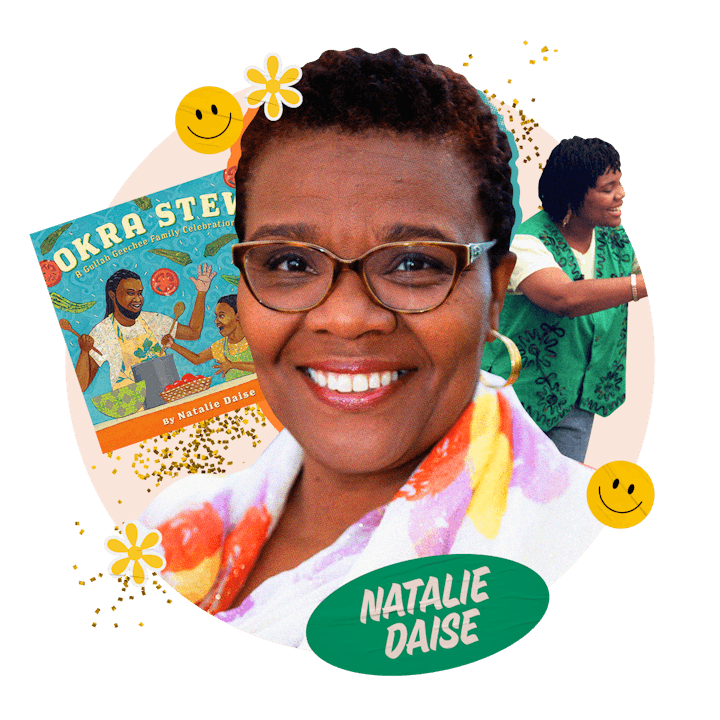

Gullah Gullah Island’s Natalie Daise sits down with Scary Mommy to discuss her new kids’ picture book, Okra Stew.

If you grew up in the ‘90s like I did, you probably remember Gullah Gullah Island. From 1994 to 1998, the educational Nickelodeon series took kids on a magical adventure to a fictitious island filled with family, sea creatures, and kindness (plus Binyah Binyah Polliwog, of course). Created by real-life husband and wife Ron and Natalie Daise, who also hosted the show, Gullah Gullah Island brought the West African culture of Gullah Geechee to life for young viewers.

Now, 25 years later, Natalie Daise is bringing that culture to kids again through art with her debut picture book, Okra Stew, which authentically explores Gullah Geechee culture through a staple dish.

And considering the dearth of Gullah representation in kids’ lit, the book comes none too soon. Okra Stew bears witness to many Gullah Geechee practices, from passing down cooking utensils through generations to making sweetgrass baskets.

In the book, Papa and his son Bobo prepare something special for dinner: okra stew, just like their ancestors used to make. Bobo helps Papa pick fresh veggies from the garden, catch shrimp straight out of the creek, “rain down” rice in the pot, and more in preparation for a meaningful feast.

Just ahead of the book’s launch, Daise sat down with Scary Mommy to chat about the importance of food, family, and Gullah Geechee culture.

Scary Mommy: Family plays an integral part in a lot of your art. In our plugged-in society, how can food bring you back to center?

Natalie Daise: It's interesting because of the generation in which I raised my children. It was just very important to be present, to listen, to connect. When my children were little, my stepmother — who’s a wonderful woman — said, ‘I want you to remember the relationship you’re building is with the adults they’re going to be.’

I needed that because when you’re in the middle of raising them, you’re right there, which you should be. But also, these are human beings. They’re whole people all themselves. And to interact with each of them as the whole person they are is something we always did so that now that they’re adults, we’re all friends. We care and have a lot of respect for each other.

SM: You’ve said your kids were less plugged in than most. How did you encourage that?

ND: We played games, and we talked, and we laughed. And what we would do on long car rides was tell stories.

They were also read to from the womb. Ron was like, ‘I'm reading to my child.’ I said, ‘No, you're reading to my stomach.’ (laughs) But we read to them from the moment they got out. The ritual of every evening curling up on the bed and being read to started when they were just infants. There was that connection always.

Make the effort, if you can, to share a story or read a story. If they are plugged into a screen, sit there with them and analyze it. My children say we ruined them because they cannot watch anything without thinking, OK, why did they do that? What are they thinking?

SM: This is so much more complex than just a simple question and answer, but can you describe the Gullah Geechee culture a bit?

ND: The Gullah Geechee culture is simply the passed-on heritage of those who were brought from Western Africa, particularly to grow rice on the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. These West Africans were brought from rice-producing countries because they were skillful in rice production and lived here on the coast, where they were able in some ways to sort of develop an African community that had traditions that have been passed down — from language to food to other cultural practices that are still here.

That's the simplest way I can explain Gullah Geechee culture. It is a language, it is a culture, it is a people. But what is in common is ancestry on the rice coast of Africa and a community built even during times of enslavement to have built a community along the coast. And the fact that because of the temperate of the weather here for many, many, many years, this area was probably 70 to 90% African in many communities. The Europeans would be like, ‘It's hot. We're going inland, we're moving up….’ So, through generations, there were Africans who passed down their heritage working the rice plantations.

You call that Sankofa: reaching back and bringing forward. That's what the spirit of the book is. Reaching back for those things that have value and bringing them into the future.

SM: The star recipe in your book is okra stew, and listen, I'm an okra girl through and through. But kids can be really squirrelly about it. What’s your secret for getting them to try it?

ND: Probably the most palatable way is fried okra. It’s crunchy, it's salty. They can pick it up with their fingers. Simeon [Natalie’s son] loved fried okra. I love stewed okra, and I love to cook with it — and if you cook it right, it's not slimy. When you make the okra with stew, it's not going to be slimy because it's cooked at the right temperature. But fried okra is a real easy entry. It's a nugget.

SM: This book speaks so much to how heritage and food are intertwined. What are some other great ways parents can help kids embrace that?

ND: One way in the book is to want the children to help you with food and to talk about your own experiences with food, like if you have been lucky enough to have had experiences with your elders. I still make my grandmother's sweet potato pie. My Daddy taught me how to cook greens. I taught my children how to cook ... Just talking about it through the story and through the act of working together.

A child who reads this book might want to try okra stew or not, but they might want to help make cornbread, which is lovely and good and tasty. If you don't have a recipe, get some Jiffy and still make it a part of that experience. Food is a wonderful way to celebrate heritage, to learn new things, and to bring family together. Everybody got to eat!

SM: So many parents want to honor other cultures but don’t want to appropriate or be disrespectful. What are some things families can do to teach their children about Gullah Geechee culture?

ND: It is really interesting, the question of appropriation. Some things are just appreciation. And so to do a recipe, to buy a piece of art, to get a book is not appropriation. It's appropriation to take something, call it one's own, and not acknowledge its origin. That's appropriation.

But to say, ‘Oh, hey, we're going to make this thing. This is an African recipe, or this is a Gullah recipe,’ that's appreciation. That's wonderful, that expands us, that makes the world bigger for us.

Right now, it's very important for us to keep our world from closing in. Also, at the same time, find a way to hold hands with doing that. Like, ‘Wow, this is wonderful. And also we have this, and that's wonderful too.’

I cook cornbread in my great-grandmother's cast iron pan. I mix things in the bowls Ron's mother used when she got married. These are little artifacts I painted and put into the book because those things are important. They hold stories.

SM: Hearing you talk about these recipes, it feels like a cookbook in the making. Just putting that out there.

ND: I hadn't thought about it. Now, I don't bake. Ron bakes these amazing cakes — there's no reason for me to bake. I used to bake pies all the time, but I’ve got to tell you, in the last few years, my creative energy has moved out here (gesturing to paintings in the background). I hardly cook at all.

My daughter is an amazing cook, and she lives here. She made gumbo the other day, and she used okra, shrimp… the whole thing, like my stew. She did a really great job with it, and I ate it. My engagement with food mostly is to eat it.

SM: Maybe your family will consider publishing a cookbook one day that you share with all of us?

ND: That actually sounds like a lot of fun.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.