High School Sports Are Struggling To Enforce Concussion Laws

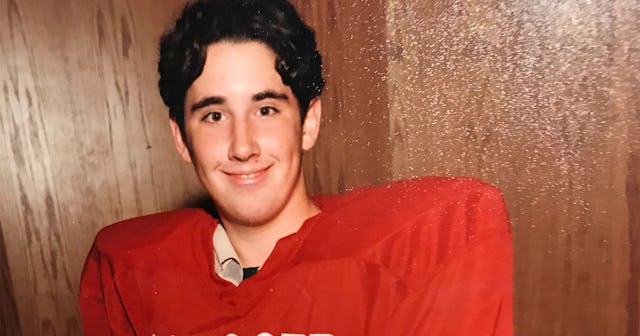

My husband Matt was just 13 years old when he joined his first local football league. A huge fan of the sport, Matt was more than ready to give his all to the game. He hustled hard, loyally followed his coaches’ feedback, and toughed his way through the most challenging of moments.

He also never spoke up when the intensity of each practice took a dangerous toll on his physical and mental health. Back in the day, helmet-to-helmet contact was not only allowed, it was repeatedly encouraged.

“The whole time we’d be practicing, it would just be us hitting each other with our helmets over and over again, and it felt like it went on forever,” Matt says. “You’d jump off the line, lead with your helmet, and then you hit. That was just the way we played, over and over again.”

Quite unavoidably, my husband encountered minor concussions while playing. But there was one in particular that left him especially debilitated. “I remember I got a very bad headache in the middle of practice and had a buzzing in my head. And then after that, I was nauseous and dizzy,” he explains. “I think there was a little part of me that knew it was a concussion because I was telling myself not to take a nap. I had heard that it wasn’t a good thing to fall asleep if you’ve had one.”

Since Matt’s coaches were of the old school “hang tough” mindset and toxic masculinity reigned supreme on the field, he never felt comfortable to talk with them about his head injuries. He also didn’t tell his parents or anyone one else for that matter. While this allowed him to easily play several more seasons of football, Matt had no clue of just how long-term the damage from his concussions would ultimately be.

“I don’t think I fully knew what was going on and certainly didn’t know how bad they were back then – or that it was even a brain injury,” he shares. “Nobody ever talked to us about them at all, even in football.”

The good news is that rules have finally been put into place in every state that can improve a school’s chances of sports-related concussions being prevented, identified, and treated. The bad news is that many schools are without the necessary resources and education required to actively put these rules into tangible practice.

These new regulations are something Matt and others like him would have greatly benefitted from as a young student in sports. But our youth are still facing the same exact obstacles Matt experienced, because these rules don’t empower coaches to create a safe space for ongoing discussions about head injuries. Which makes total sense, as schools are being forced to change policies to ensure our children’s safety, but they aren’t becoming fully equipped with the tools needed to communicate with their students effectively.

Courtesy of Lindsay Wolf

A new study conducted by the researchers at the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital sheds light on key barriers faced by schools when implementing each of the three core components of concussion laws: education, removing athletes from the game, and returning them back to play.

Dr. Ginger Yang is the principal investigator who led the study, and she believes that by openly talking to athletic trainers, we can overcome the roadblocks that keep them from putting these policies into action. “These laws exist on paper, but we need to understand how they are implemented in schools and the challenges that arise in order to determine if they are truly effective,” Yang says in a press release for the study.

According to her findings, the educational materials that are being used in most schools are littered with complex medical language that keeps parents and coaches from feeling engaged enough to teach the best ways of preventing concussions. What’s more, you can’t see a single outward sign of a concussion, which makes identifying them beyond difficult.

Just like my husband when he was in high school, many student athletes also still feel pressured by coaches and parents to stay in the game no matter what. This leads teens to hide their symptoms as a way of not being a risk to the team, which can make removing them from the field tremendously hard.

There are also an overwhelming amount of students who simply don’t have access to the specialized care they need to properly treat a head injury, which further exacerbates an already challenging problem.

“Concussions need to be diagnosed clinically after a doctor assesses how the injury happened, analyzes the symptoms that developed, and completes a neurological exam,” said Sean Rose, MD, co-director of the Complex Concussion Clinic at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

Unfortunately, doctors can’t even begin to assess a concussion if a student has no way of being medically screened by them. Which means that many injuries can go unreported — and even worse — untreated. When a sports-based concussion goes without treatment, it can have a lasting impact on the brain and body. Which means that experts in the field need to focus immediately on addressing the inherent challenges in these new policies and determine how they can be efficiently carried out by the adults in charge of our student athletes.

In October 2019, a no-nonsense PSA went viral as part of the “Tackle Can Wait” campaign, an effort designed to shed light on the dangers of signing children up too early to play the game. The goal was to encourage parents to wait until their kids are at least 14, because delaying their exposure to tackle football can greatly reduce their chances of having long-term brain trauma. “Tackle Can Wait” is a movement created by two daughters of former NFL players who died from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease found in people who have had multiple head injuries.

Both professional athletes weren’t even diagnosed with the disease until after they died from it.

It’s important to note that the above is just an example of two post-mortem CTE cases in adults. Children, on the other hand, have brains that are still very much developing during their adolescent and teen years. Which means that a sport like football can leave them unbearably vulnerable to head traumas that could last their entire lifetime.

And while concussions are certainly at the top of the list of concerns, it’s also critical to know that kids under the age of 12 who incur even minor head injuries while playing tackle football are at a much greater risk of struggling with clinical depression, clinical apathy, behavior deregulation, executive functioning dysfunction, and impulse control.

As a result of playing just a handful of intense seasons as a young teen, my husband is still struggling with the lasting effects sports-based head injuries have had on his mind and body. “I feel like I’m very prone to headaches a lot of the time now, and I think the migraine issues and a lot of other issues tied to my anger or any kind of erratic or depressive behavior stem from football,” Matt says. “It probably didn’t help that I was bashing my brain around for so long.”

When asked if he’d ever be open to having our children play the sport, Matt’s a hard “no” on the subject.

His reason? “There’s no way for a kid not to get their head injured in tackle football,” he shares.

I’m going to have to passionately side with my husband here. And I think it’s safe to assume I’m not the only one who will. The fact of the matter is, we can’t afford to wait any longer to change the course of an urgent conversation that so dangerously affects our nation’s youth. With roughly two million of our country’s kids and teens suffering from sports-related concussions each year, it’s time to finally make it easier and more practical for coaches and parents to keep students safe on — and off — the field.

This article was originally published on