My Brother Murdered Our Mother, And I Believe I Know Why

On September 25th, 2007, my brother murdered our mom. And over the last 14 years since, I have received the same question over and over an innumerable amount of times: “Why?”

To me, this implies there’s a plausible reason for her murder, which I don’t necessarily agree with. But still, I had to ask myself the same thing, if for no other reason but to avoid our family history repeating itself. And in the process, I realized the question really implores, “Where does such extreme hatred come from?”

First, a quick disclaimer: I am in no way an expert on this subject; I have no impressive degree from an Ivy League school. However, I grew up in a household in which one of three of its members was filled with a hatred so compelling it sparked fatal violence. Thus, I’d like you to consider my theory on the subject as a result of a twenty-two year case study.

So, why did my brother come out the way he did?

I am a firm believer that no one is born with the desire to hurt others. We, as humans, naturally need each other to survive. Some of us may be more genetically inclined to be aggressive, but our relationship with others is greatly social. So, why is it that some can ruthlessly murder others while others dedicate their lives to improving society?

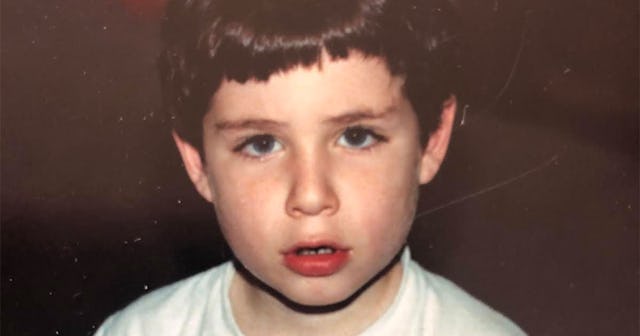

Courtesy of Amy Chesler

I believe the difference is simple: attachment.

I have been told Jesse seemed “different” as early as the age of three. This was the age my father left our family. This was the same year I was born. The same year my mother was forced to become a single mother. All of these factors would change someone. I have two children not much older than the age of three. I feel the incredibly strong attachment we have to each other – if I left them now, I am sure it would affect them infinitely. It would cause a little piece of them to disappear – their confidence, stability, and feeling of security in the world would lessen.

But would it cause them to hate others indefinitely? To lash out and desire to hurt people? I don’t believe so.

Courtesy of Amy Chesler

And what if they experience a similar abandonment by others over time? Well, the more isolation we as humans experience, the less empathy we possess towards the world we feel disconnected from.

This was my brother’s case.

He was short, he was teased, he was never really accepted by his classmates. He was ostracized for characteristics that were out of his control. He had been diagnosed with Tourette’s Syndrome as a young child, his tics making him seem even less “normal” than he already was. His behavior became more deviant as time went on, as his laundry list of diagnoses increased. He began to get into fights at school. He was angry and volatile. His school did nothing; this was not in the sensitive days of late. Back then it was “kids will be kids,” and “Do you think he’s cut out for school? Maybe he should get his CHSPE.” He truly was an anomaly in our affluent community of Calabasas, where more students nab a perfect SAT score than drop out of school.

So, in short, as he entered young adulthood and attempted to find connections, everyone but my mother told him he was not worth the trouble. Mom believed in him infinitely, as parents do for their children. She knew he was capable of so much more than what people had begun to expect of him. The pressure to meet my mother’s standards despite everyone else’s grew too much for him though, and he attempted suicide twice. At this same time, he began to get physical with us as well. He often punched, hit, and kicked us or the walls of our Calabasas homes.

Courtesy of Amy Chesler

Beginning in middle school, I watched these trials. I watched society tell Mom what she was doing wrong. I watched society tell my brother how much less value he held because he was different, and how he ought to behave to fit in. I watched them both fail over and over, and everyone around us tell us how we were screwing up, instead of offering help. It was nearly unbearable for me to witness; I cannot even begin to conceive how hard it was for both of them to go through. And it only got worse over the years. He often executed physical attacks on our bodies, property, and minds.

Our increasingly tenuous relationship forced Jesse to leave home for a bit when he was around 22. Mom could no longer allow him to live with us if he couldn’t control his anger. Unfortunately, his stint away delivered him into a volatile military career. It only took a few months before it came to a screeching halt and his mental illnesses became apparent; he had chosen to stop concealing them under the duress of boot camp. He somehow exited with honorable discharge, and still, very little mental health benefits. And upon his return home to Mom, he felt even angrier and more isolated.

Courtesy of Amy Chesler

And, to make an incredibly long and painful history shorter, after twenty-five years of being told he was different, feeling little connection to those around him, and being attached to nothing but his desire to make people feel as little as he had all his life, Jesse stabbed Mom to death.

But, quite often people like Jesse hurt strangers. They pack their cars with weapons and their minds with plans, and execute others while they’re at school, sitting in movie theaters, or celebrating their freedom. Because people like Jesse, who have never really attached to anyone soundly, often feel the need to show others just how awful this isolation can feel. That’s where the hatred comes from.

Courtesy of Amy Chesler

So, a better question is, what can we do to change this?

Although these heinous acts are surely the responsibility of their perpetrators, I believe there is always something we can do to improve our chances of love over hate. Isolation and anger are normal emotions, and most of us learn to digest them on our own. But there will always be those in our society that place responsibility on others, and seek to exact revenge as my brother did. Thus, it cannot solely be our government’s job to restrict guns more. And it is not only about how a parent has failed their deviant child. It’s less about guns and parenting (although stricter laws on both cannot hurt our children more than the guns literally have).

Courtesy of Amy Chesler

This is about love. No matter if you’re Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Atheist, Greek Orthodox, Agnostic, Democratic, or Republican. No matter your gender, sexual orientation or socioeconomic status, our duty as humans is to help others. To open our hearts to others and aide those in pain and in need. Allowing people to feel part of the human race or tribe, rather than an anomaly or a member of a smaller, less important faction, that is what will end the hatred.

As the Red Hot Chili Peppers sing, “Red, black or white, This is my fight, Come on courage, Let’s be heard, Turn feelings, Into words.” Let’s start a dialogue that allows everyone to be heard and feel accepted. Then, and only then, will we see the hatred begin to melt away. And until we can open our hearts — stay safe, everyone.