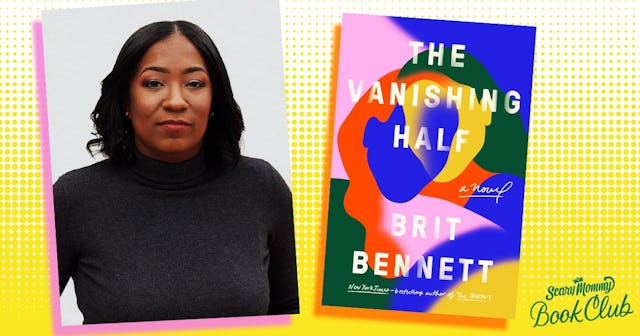

Brit Bennett Talks About Writing 'The Vanishing Half'

A conversation with Brit Bennett, author of The Vanishing Half

Q. In this book, you write from a number of perspectives, spanning different decades and ages. How did you manage to shift back and forth from all of these voices? What was it like alternating between two different generations of family living in different decades?

A. I love novels that tell stories of communities. I knew that The Vanishing Half would mostly be a story centered around twin sisters, then I realized I also wanted to spend time in the perspectives of their daughters and explore both sides of the mother daughter relationship. The story became more like a baton being passed from character to character. Of course I loved writing the women, but I also loved writing Early Jones, this grizzled man who takes great comfort in his stoicism although he is secretly full of feelings. There’s always something fun about writing from the perspective of someone who rarely says what he’s actually feeling. Aren’t we all, to some degree, reluctant narrators? I also really enjoyed the character of Kennedy, who is so unlike me. Her voice is endlessly, breathlessly chatty and she doesn’t take herself very seriously. At the same time she oscillates between being self-aware and self-deluded in a way that made her interior life fun to explore.

Q. The main characters of your book are identical twin sisters who are from a town in Louisiana that has a particular obsession, can you talk about that town and where you got the idea for it? How is this town significant to the story of these girls and what follows?

A. The novel was sparked, a few years ago, when on the phone, my mother offhandedly mentioned a town she remembered from her Louisiana childhood where everyone intermarried so that their children would get progressively lighter. This struck me as so strange and disturbing that it felt almost mythological. I always understood that lighter skin confers certain privileges within black communities and white ones, but I began to think about what it would be like to grow up in a community so committed to engineering light skin that it would govern who you might be able to marry. I started to think about how two characters might react completely differently in this situation. Twin sisters, one who decides to pass for white and one who moves back to their hometown with her dark-skinned daughter.

As far as the town itself, I wanted it to feel like another character hovering over the story. That’s the strange thing about home—no matter how long we’ve been gone, it never quite leaves us. I was particularly interested in the town’s effect on Desiree’s daughter, Jude, who we first see as an adult as she is leaving home for college in Los Angeles. I became interested in the way she carries this rough childhood with her. How does she carry the harm this town has done to her all the way to California? To me the lingering effects of the brutality are more interesting than the brutality itself. How do we carry the pain of home with us even when we leave?

Q. The twin sisters grow up in the same small town and have basically identical experiences and yet their lives go in radically different directions. Can you talk about their parallel lives and what you’re trying to explore about identity?

A. I have two older sisters so I’ve always been interested in sisterhood itself: how can you share genetics and grow up in the same house but turn out to be completely different people? In some ways we’re shaped by our siblings. My oldest sister turned me into a basketball fan and I played violin as a kid because my other sister was in the orchestra. But on the other hand, I often wonder what parts of me are reactions to who my sisters are not. How would I have been different if raised an only child or raised in a different family altogether?

In The Vanishing Half, Desiree and Stella live vastly different adult lives based in two separate racial realities. But beyond the effects of race and wealth, I wanted to think about how these women become so different from each other, within their careers and even their relationships with their children. I loved the idea that their diverging paths can be traced back to one simple choice: at a job interview Stella gets mistaken for white and chooses not to correct it. At the time, this decision feels like the necessary and reasonable path to take, but later, Stella understands it as the first domino that falls and alters the rest of her life. I like the idea of a small moment proving to be so consequential. While writing this book, I loved thinking about how we are all constantly remaking and unmaking ourselves with the choices we make every day.

Q. As you touched upon, one of your light-skinned black twins is mistaken for white, and realizes that she can create a life passing for white. She separates from her family, and creates an entirely different identity and fictional past. There is a long history of passing in this country. Did you research it at all, did you have other people’s experiences in mind as you wrote Stella’s story, or did you think only in terms of this character? Is there a question of morality in passing? Did you research the history of passing in America?

A. I read a few academic books on the history of passing in America. I was mostly interested in the unknowability of it. In a way, passing is like faking your own death. There’s no way of knowing if someone has done it successfully; you can only recognize the people who are caught or reveal themselves. Growing up, I always thought of racial passing as an act of self-hatred, or perhaps even less interestingly, opportunism. I could understand why a black person, living in the early twentieth century, would want to escape discrimination and violence, but I considered it cowardly and weak. But I think that’s a morally simplistic way of understanding passing, and I’m never interested in moralizing in fiction. What became more interesting to me was the idea of passing as an act of self-destruction and self-creation. What do we gain and lose when we decide to become someone else?

Traditionally, the passer is a transgressive figure. By crossing among social categories, she proves that the categories themselves are constructs. How real is race if it can be successfully performed? And what does it mean to structure a society around a form of identity that is, essentially, performance? At the same time, passers often end up reaffirming the hierarchies that they pose to topple. In The Vanishing Half, for example, Stella becomes the face of a neighborhood committee aiming to prevent a black family from moving in. She finds herself embracing the same white supremacist violence that she once herself faced in order to secure her position within her white community. So Stella becoming white doesn’t threaten white supremacy. She just begins to benefit from it instead of suffering at its hand.

I wanted to sit in the complexity of this, without condemning Stella for her choices. I wanted to understand why she might choose to pass for white, which in her case is neither self-hatred nor opportunism. She’s a woman who witnessed horrific violence as a child and she wants to be safe. When I began to think about passing as a type of death-faking, I started to understand Stella better. Who hasn’t wanted to start over in life, particularly to leave behind some tragic memories? Who hasn’t wanted to be a new person?

Q. Like in your first novel, The Mothers, this novel explores the relationship between mothers and daughters. What draws you to this dynamic in your fiction?

A. I just like stories about women taking care of each other or failing to do so. Mother-daughter dynamics are fun to explore in part because they carry so much weight—our relationships with our mothers hang over our entire lives. And in many cases, daughters go on to become mothers themselves and hang over their own daughters’ lives. My first book was about unmothered girls. In this novel, I wanted to explore the complex relationships these women have with mothers who remain in their lives. I think the other big shift in this second novel was spending more time in the point of views of the mothers, not just the daughters. There’s a brief section about Adele, the twins’ mother, who recalls the impossibility of loving two people the exact same way. She blames herself for Stella disappearing and wonders if her treatment of her daughters led to their diverging lives. So I think that while The Mothers is about absent mothers, The Vanishing Half is about mothers trying, and often failing, to do their best.

Q. One of the twin sisters remains in the small town they grew up in and the other leaves forever, essentially erasing her past. Can you talk about the role of place in the novel? How does where we are from imprint us or stay with us after we leave? Similarly, how does the trauma the twins inherit from their past linger with them in different ways?

A. In The Vanishing Half, the twins witness a central traumatic event as girls: their father is lynched in front of them. But although both girls witness this event together, they both react to it very differently. Stella, in particular, remains haunted by this unexplainable act of violence and her sister’s unwillingness to talk about it. She spends her life running from this specter of violence that she can never make logical sense of, or even discuss with her husband or daughter. I do think that geographical movement can be an impetus for change, or at least, free us to try out new identities. Stella eventually has to move away from Louisiana in order to feel like she can truly start over. Desiree, on the other hand, returns home to live in the house where her father was killed, which forces her to live alongside the trauma instead of fleeing it.

Still, regardless of the twins’ approaches, both of their daughters inherit this family trauma. I became interested in how this violence might trickle within the rest of the family, particularly given that one second generation daughter knows about the murder her mother witnessed, but the other doesn’t. And yet the one who doesn’t know about it still suffers these horrible nightmares. She feels puzzled by her mother’s hypervigilance. What does it mean to feel burdened by trauma that you can’t even explain?

Q. The character Reese isn’t trying to change his race but is transitioning to a different gender. How do you see questions of race and gender being similar or different? Would you consider what this character is doing a different form of “passing”?

A. I think the similarity is that race and gender are both constructs that are far more complicated than a binary way of thinking leads us to believe. But what was interesting to me about Reese is the way that his journey serves as a counterpoint to Stella’s. Reese undergoes physical changes that affirm who he is. Stella does not change at all physically but by the end of the novel, she has become a completely different person mentally and emotionally. By putting those two characters in tension with each other, I wanted to explore the complexity of transformation. What does it actually mean to change? Change doesn’t always look like what we think it does.

Q. Reese and Jude’s story is such a moving love story. Can you discuss the role of romantic love in the novel—for the twin sisters as well as for their daughters—and how it compares to familial love?

A. I think there are a lot of unconventional love stories in this book. The central relationship is between sisters who separate as teenagers and spend their adult lives apart, but in spite of this distance, their love for each other binds them together over decades. Stella has to navigate a marriage built on secrets, and Desiree enters this long-term, long-distance relationship with a man she refuses to marry. Love appears in all sorts of ways, across distance and time.

That being said, I’ve always thought of the relationship between Jude and Reese as the romantic center of the novel. What interested me about the two of them together is that these two characters, for very different reasons, have grown up experiencing violence and shame surrounding their bodies. So to me, the question was, how do you learn to love yourself when you’ve been taught to hate yourself? Or even beyond that, how do you learn to be loved by someone else? Their relationship is a constant dance around trust and intimacy, and there was something beautiful to me about watching them struggle together because they care about each other so much.

This article was originally published on