‘Black Boy Joy’ Shows The Diversity Of Black Boyhood, And It Is Powerful

Black Boy Joy is a term coined by writer Danielle Young for The Root. This is what she had to say about the term back in 2016.

“The climate in America right now is hostile, to say the least. Black men are dying at the hands of authority figures, and witnessing #BlackBoyJoy is a rare, much-needed break from the tragic headlines and hashtags. And let’s be real—the world is highly critical of young black men who express joy. So I want to celebrate this idea that young black men can be happy, too.”

Some people took issue with the use of the word “boy,” but Young also explained why she felt it was necessary.

“I realize the negative connotation around the word “boy” and recognize the racist history of its use by white supremacists throughout our dismal history. But I did not reach back to the 1800s and yank out the tongues of slave masters to taunt black men with the word “boy”; I wanted to remind all of us that there’s a beauty in black boyhood that’s often ignored and that our boys are forced to be men much too soon.”

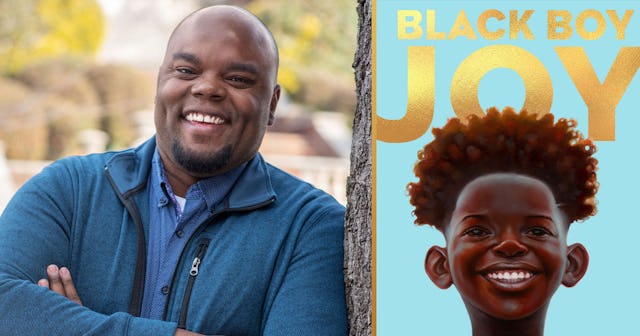

That beauty in boyhood is exactly what author Kwame Mbalia wants to capture with his new anthology, ‘Black Boy Joy.’ He is not the only author in the book, he teamed up with 16 other Black male and nonbinary authors, two of whom are unpublished. Some of those contributors include authors Dean Atta, B.B. Alston, and Jerry Craft (“contrary to what many would have you think, there are way more than sixteen Black male and nonbinary authors,” Mbalia says.) Each story explores Black boyhood in different ways. Scary Mommy got the opportunity to ask Kwame Mbalia some questions via email about ‘Black Boy Joy.’

Bryan Jones Photography

“This idea really came to life over the summer of 2020, during the Breonna Taylor and George Floyd protests,” Mbalia said. “There has always been this tension, this thing where I hold my breath, or tighten my shoulders, or close my eyes whenever a Black person appears on the news, like an instinctive thing my body does in preparation for horrible news. And I wanted to combat that. I wanted to, specifically for Black boys, provide a respite.”

Too often, the only Black stories that get told are the sad ones. And while it’s important to reflect on our collective pain as a people, there is so much more to our story. Mbalia felt that it was important to create ‘Black Boy Joy’ as a way to remind all of us of that joy, but especially young Black boys who often aren’t allowed to experience or reflect on their joy.

“Black joy is beautiful, and yet it can be stamped out of our boys for many reasons: Toxic masculinity, peer pressure, and a constant reminder from the media that the only interesting stories are the ones centering pain. But life is a balance of emotions and writing about Black Boy Joy is an attempt to uplift that oft-forgotten part of our lives.”

And that’s exactly what he and the other authors do. Each short story explores a different aspect of Black boyhood, and does so beautifully. When we talk about Blackness, people outside of the diaspora often don’t realize (or forget) that Blackness is a spectrum. There is no one way to define what being Black is. As much as people try to boil us and our experiences down to one palatable thing, that’s simply not possible. Black people are not a monolith, and we all deserve to have our stories told. Of course, ‘Black Boy Joy’ only tells 17 stories, but it gives voice to the 17 types of Black boys who don’t get to hear their stories told anywhere else.

“I wanted writers whose work I found joy in, or who made me laugh, or who I’ve met before and couldn’t help but be joyful in their presence,” Mbalia explained.

Penguin Randomhouse

My personal favorite story in ‘Black Boy Joy’ is ‘The Legendary Lawrence Cobbler’ by Julian Winters. Probably because it focuses on cooking and baking, which are two of my favorite things to do, and also two things that feel intrinsically tied to my Blackness and Black experience. Food is so important in Black culture. For so long, it was all we had, which is why we’re precious about things like mac and cheese and potato salad. Cobbler is another one of those foods that are a perfect representation of the Black American experience.

In Winters’ story, his main character, Jevon, uses food and cooking as a connection to his father. That’s another example of the Black experience — many of us found connection to our elders in the kitchen. I remember making special meals with my mom as a kid, and now my son and I use baking cookies as a way to have some quality time. Jevon comes together with his dad and grandmother to make their “legendary” peach cobbler, and while they’re baking, Jevon learns about a connection he and his G’Ma share that goes beyond food. And that no matter what, family has each other’s back.

Unlike me, Mbalia doesn’t have a favorite story in ‘Black Boy Joy’, and I can understand how he doesn’t as the person who chose the authors for the anthology.

“I loved the adventure in Don P. Hooper’s story as well as the support of friends and family in both George M. Johnson’s story and in Julian Winter’s story,” he said. “I laughed nonstop at Lamar Giles’s story and nodded in recognition as I read Jason Reynolds’s. Every story provided me with an emotional response that carried some representation of joy.”

It’s important to note that ‘Black Boy Joy’ is a book aimed at middle grade readers, much like Mbalia’s other books. Every author finds their sweet spot when it comes to finding an audience, and Mbalia really seems at home in the middle grade space. I was curious as to why, and his answer certainly didn’t disappoint: “My sense of humor has never graduated beyond middle school. One of my greatest creations is the poop zombie,” he said. (Full disclosure, he told me I wasn’t allowed to edit that part out. And truth be told, I wouldn’t have.)

And with an answer like that, it’s not surprising that this anthology is aimed at a slightly younger audience. Black boys should be able to revel in poop zombies and not have to always worry that the world is unsafe. This book is a prime example of being able to focus on the things that make Black boys the same as anyone else, but also highlights the uniqueness of the Black experience.

In a world where it’s hard to merely exist as a Black person, especially a Black male, we have to remind ourselves and our boys that joy exists. Not only that, but they’re just as deserving of it as their non-Black peers. As a Black woman, I find my joy in the abundance of experiences we as a people have. Of course, as the editor of ‘Black Boy Joy’, I had to know how Kwame Mbalia finds joy in his Blackness.

“I find my joy in Black people. Our very existence in many instances is a story of rebellion, of resistance, of living in spite of. And yet it is also a story of beauty, of peace, of crinkling eyes and knee-slapping laughter, of a shared joke between friends and a shared look between strangers who happen to be the only Black people in a room.”