Postpartum Depression Almost Took My Life

It was an unseasonably warm day in late January, two weeks after the birth of my first child, when I considered if she would be better off if I were dead. Strolling along the scenic and busy Kelly Drive in Philadelphia pushing the stroller that, for the past several months, I had imagined myself using while happily gazing at my sleeping beauty, I suddenly envisioned throwing myself in front of oncoming traffic.

What scared me wasn’t the thought itself, but the immediate relief I felt at the idea that I could put an end to not only my motherhood, but also my suffering.

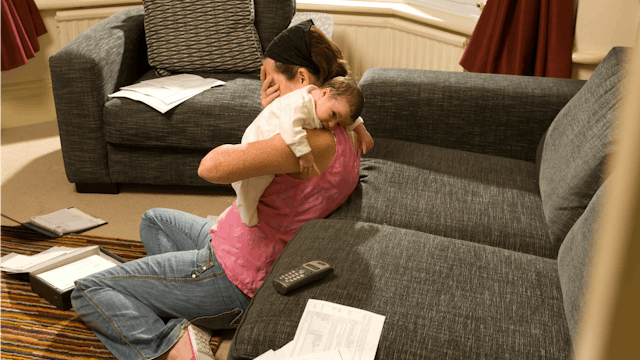

Like the estimated one in seven new mothers, I was struggling with postpartum depression (PPD) and it didn’t just rob me of the fleeting moments of my new baby’s life—it marred my memories, inflamed my guilt and depleted my sense of self worth. I remember thinking that I should have felt happy, but I was not. I should have wanted to hold my sweet girl. But I couldn’t. I should, above all, have felt grateful for the healthy miracle that was mine… she who I had dreamed of, longed for and wanted beyond belief. But all I felt was resentful as my life changed in ways I hadn’t prepared for, emptiness as I struggled with the rapid changes my body was making back to its non-pregnant state, and above all, fear that I’d made a mistake and couldn’t be the mother my daughter deserved.

My struggle shouldn’t have come as a surprise. In fact, I was given a survey in the hospital called the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, meant to assess a new mother’s risk for PPD. I had multiple risk factors. I was a military wife on my own with a gaping lack of support. I had a history of anxiety and current or recent stressful life event. Unsurprisingly, I scored very high-risk for PPD. I should have been followed from the moment my daughter exited my body. Yet no one from the hospital or my providers office reached out.

Having worked within the mental health community, I realized that day that I needed help and quickly. Yet, as informed as I was and as much as I considered myself an advocate against the stigma of mental illness, actually asking for help when you feel like you’re in a boat without oars is hard. It was the unyielding insistence of a friend that led me to contact my OB-GYN’s office and I finally got seen two weeks after I began to dabble in suicidal ideation. I did get help and got better. But I’m worried about the moms who don’t.

After 40 weeks of pregnancy, in which I interacted with my healthcare provider a total of 16 times, it was shocking that I’d be allotted one postpartum visit six weeks after giving birth. As a friend said recently, her daughter saw a provider five times in her first month of life and all she had to do was be born; whereas my friend delivered by major abdominal surgery and wasn’t seen once. This is how the current model of care is failing new mothers, including their mental health. Most women begin to experience worsening symptoms of PPD around two weeks postpartum and yet, they must still wait a month before they are evaluated.

But it’s deeper than just getting in to be seen. Most OBGYNs are not trained to treat PPD or may not be comfortable, believing that it’s better managed by specialists. This is a problem when there is a shortage of psychiatrists, especially those who specialize in perinatal mood disorders and are comfortable prescribing medicines to pregnant or breastfeeding mothers.

In my case, I was initially handed a sheet of paper during hospital discharge with different mental health professionals in my area… most weren’t accepting new patients and the ones who were didn’t accept my insurance. Fortunately for me, my doctor personally decided to treat me, recognizing that I wasn’t able to seek help elsewhere. Sadly, not all moms receive the care that I did.

There is hope. The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG) released sweeping new recommendations that postpartum women be seen earlier in their recovery and that ongoing care be provided as needed. In October 2018, a new app was announced by the UMass Medical School and Worcester Polytechnic Institute that will help OB-GYNs better evaluate and treat PPD in new mothers. Healthcare professionals are recognizing that mothers are being failed, putting babies and families at risk. But until the standard of care is that all new moms are seen, screened, diagnosed and treated, the system will continue to allow at-risk moms to suffer and I will use my story and voice to speak out for them.

My own journey through and beyond postpartum depression taught me so much about motherhood and its multiple facets. It can be magical and awesome, consuming you with a love you never knew existed and can’t even begin to quantify. It can be terrifying in the way that that same intensity of love makes you hyperaware at all times of what you always stand to lose. It can be a mirror, reflecting your deepest regrets as well as your greatest glories. Motherhood is hard and is a sacrifice. But what it should never be is suffering.

This article was originally published on