Why My Son's Autism Diagnosis Was The Best Thing That Could've Happened

I’ve been toying with the notion of writing about my son for a minute now. But I was at a loss as to how I’d go about doing it. They say you shouldn’t pick a favorite child … that each child is special and unique in their own way. And this statement is 100% true — no ifs, ands, or buts. But I have to say that my son, Noah, is perhaps the most resilient of my three, and for good reason.

In late 2011, I noticed that Noah’s speech was not coming along as I thought it should be. I know, I know … one should never ever assume anything should be a certain way. However, he was my first child, and I had been inundated with statistics about growth and development.

Like every mother, I wanted to ensure that my son was growing properly and was healthy. So naturally, when he started slowing down in his speech development, I became concerned.

It wasn’t until he turned 18 months that his pediatrician became concerned as well and referred him to Early Intervention. It was through them that he received behavioral therapy, and although it helped him develop some of those crucial behaviors associated with speech and language development, he still was exhibiting issues with basic pronunciation and vocabulary building.

I pushed for him to get speech therapy on top of the behavioral services he was already getting, but according to the state, he was not eligible. They said it was because we didn’t have a specific diagnosis, and because he had just started services a few months prior. This simply did not make sense to me; I knew my son needed help, and his behavioral therapist knew it too.

It was at this point that I realized that my role as his advocate was critical to his success … to ensuring that he had the support and services he needed for that success. And so I went to work.

Over the course of that summer, I had Noah’s hearing and adenoids checked. I won’t lie; I was hoping, praying that he might have sustained some hearing loss, or that perhaps there was some dysfunction that lie within that ear, nose, and throat area. I figured that would, at least, give me some answers as to why my son couldn’t communicate with me.

I enrolled him in day care, part time, with the hopes that being around other children who were talking would serve as role models to emulate. And although he sustained other benefits from such a setting, talking was not one of them.

I was at a loss. I had no map, no answers, no nothing, and “hopeless” wasn’t even the word I could use to describe the vast array of emotions I was feeling at the time.

I began to blame myself. During the course of these assessments and evaluations, I answered a plethora of surveys, most of which began with pregnancy and birth questions. I began to think back over my pregnancy.

Was there something I ate maybe that might’ve led to this? Or perhaps I was too stressed in my previous job that it transferred to Noah. Or maybe it was that stupid music that my company insisted on blasting during business hours.

I should’ve left, I thought to myself. I should’ve found new work, or maybe moved back home. Was it my being too active? Or maybe I wasn’t active enough. Should I have read more poetry? Seuss, maybe.

I felt lost. I felt frustrated. And most of all, I was pissed. I tried to do everything in my power to be a good mom. I was engaged with my child, from the time I knew I was pregnant with him. I had done everything right, and this was my reward?

And then it hit me. There was one test I had yet to inquire about, one assessment of which I was scared to death. One evaluation that I knew would change the course of my son’s life. I had made the decision to get Noah tested for autism, with the idea that it was better to rule it out than to not even consider it a possibility.

At the mere mention of this, I angered the one person who knew my son as well as me … my husband. It was one of our more acrimonious arguments, in which he blamed me for wanting to find something wrong with my son.

Of course, I was hurt by his accusation. But more than that, I was furious! I couldn’t understand how he could be in such denial about there being a possible issue in Noah’s development. It didn’t mean that I wanted to find something wrong with him. I just wanted some damn answers.

As a mother, I wanted to help my son; I wanted to fix the problem. What kind of parent doesn’t want to do that? This strain would remain over the course of the next few months.

My family was insistent that there was nothing wrong with Noah, that he simply would grow out of it. I wondered how they could feel this way. And in those moments, I felt the most alienated from everyone I knew and trusted. In those moments, it was just Noah and me, against the world, it seemed.

Robin Davis

In part, I can see why they felt that way. The history of Black children in the public school system hasn’t been a pretty one. Many of us know about Jim Crow laws and the segregation of public schools in the South. Segregation also occurred in other parts of the country, although in more subtle ways.

For years, Black children were seen as less intelligent than their white counterparts. Often, they might’ve been placed in special education or disciplinary settings, such as detention, when the surrounding circumstances did not warrant such action.

We see an example of this in the movie Hairspray. When Tracy Turnblad and her friend, Peggy, are sent to detention, they see that the majority of the school’s Black population is there, for seemingly doing nothing wrong. While this is a form of entertainment, it mirrored the reality that many Black children faced in the days when segregation was at its peak.

As such, there are those who are very resistant about even admitting that their child might have some delays or issues worth taking a look at. I’ve been witness to this as an early childhood educator and director. And there is nothing more upsetting or frustrating to me than to see a child not even get a chance at those resources out there simply because the parent is unwilling.

The history is there, and yes, it is awful, but no matter what the past has been, parents have a duty to be the advocate that their children are unable to be for themselves.

In the five years since Noah’s diagnosis, my husband has gotten a lot better about educating himself as to how he can best support our son. He has been, and continues to be, a great father.

As it turned out, our son’s autism diagnosis was perhaps the best thing that could’ve happened for him. With that “A” word on paper, Noah has received a continuous flow of support and services that I would’ve struggled to get for him otherwise. He’s been in speech now for almost seven years, has been in ABA (Applied Behavioral Analysis) therapy for four years on and off, and has had an IEP (Individualized Education Plan) since he was three years old.

Because of these services, between the ages of three and five, his development nearly quadrupled, and he was able to transition into a mainstream academic classroom with his typically-developing peers. We had met the first goal!

Now, at seven years old, Noah has extended his vocabulary, although he still gets past and present tense and correct usage of such confused and mixed up. He also occasionally drops his plural endings on words and slurs through longer sentences while reading. Furthermore, he still demonstrates frustrations at unfamiliar or undesirable tasks but is improving on identifying those emotions and applying the appropriate emotional response to those feelings.

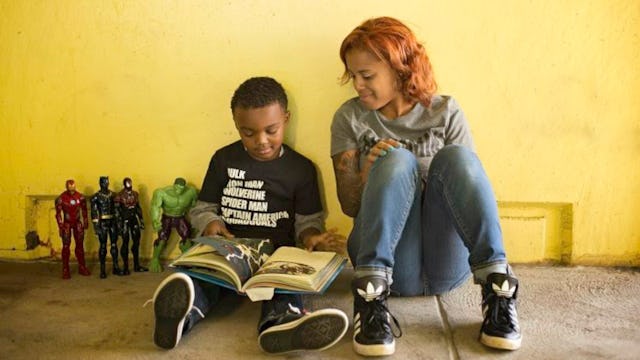

He loves to draw, and he has possibly the most active imagination of our three kiddos. He’s fascinated with history, dinosaurs, and major cities and landmarks. He’s crazy about the Avengers, LEGO Ninjago, Batman, and Star Wars. He loves to sing and dance and loves a good joke. And despite his amazing smile, he is very awkward with structured poses, as are typically seen in school photos.

He has turned into such a good kid and although he has his moments, just like any seven year old, he is constantly finding a way to overcome whatever obstacles might be in his way.

Robin Davis

I didn’t write this piece for attention, or for a pat on the back. Rather, I hope that I might bring some encouragement to some mom or dad who might need it right about now.

I know that acknowledging that your child may need additional support, that he or she might be a little different, can be a hard pill for some to swallow. And no one can blame you for all the emotions you will indeed feel if and when you receive a formal diagnosis.

Just know that you are not alone and that regardless of what challenges you might face in the coming years, your biggest responsibility is to be your child’s voice. To be their warrior.

All children come into this world with a purpose. And regardless of what may or may not be, every child has a right to be successful, and to have a happy, fulfilling life. It is our job as parents to uncover that potential and to encourage it, in whatever way it wishes to present itself.

All jewels, in their most basic form, are covered in something that appears unsightly at first. It is only when one takes the time and care to polish it that it can truly shine.

This article was originally published on