My Son Has Microcephaly

I keep reading articles about the Zika virus describing panicked young mothers filling waiting rooms and baffled doctors attempting to provide care. I look at the photographs of the infants with small, oddly shaped heads and think they look like my son Nicholas when he was born. Overwhelmed with sadness for these families, I wonder how we managed when Nicholas was diagnosed with microcephaly.

I was still asleep with Nicholas in a bassinet next to my hospital bed when the neurologists came in. Nicholas had been born in the early hours, and I had only slept briefly. Still half asleep, I tired to understand their words. “What’s wrong?” I asked drowsily sitting up in my bed. “He has microcephaly,” the one with cropped brown hair and tortoise shell glasses told me bluntly. “Didn’t you know while you were pregnant?” There began, my life “after”—a life that at moments still resembles my old life, but often feels like someone else’s. I categorize my life in before and after moments and memories.

While the doctors had been monitoring Nicholas’s head growth in utero with frequent ultrasounds during my pregnancy, they assured me, and my husband Jon, that they were not concerned because Nicholas’s head continued to grow, despite being small. After several conversations with a senior radiologist, a silver-haired man who had a face creased with smile lines and clear gray eyes, we stopped worrying. More accurately, I convinced myself that I was not worried. I suppose that in order to tolerate the remaining six months of the pregnancy I had to perform this mental sleight of hand. We could have gotten a second opinion, but this thought did not cross our minds. We were at arguably the best hospital in New York City, in a practice with doctors who had delivered many of our friends’ babies. What anxiety I was aware of, I negated.

Christine Grounds

Microcephaly is a neurological disorder in which the neurons in the fetus’s brain have not adequately proliferated in utero, “micro” meaning small and “cephaly” meaning head. A small head correlates to a small brain, as it’s the brain growth that causes the skull bones to expand. The disorder may stem from a wide variety of conditions that cause abnormal growth of the brain: syndromes associated with chromosomal abnormalities, maternal problems such as alcoholism, diabetes, rubella or some genetic malfunction. Years later, we would learn that for Nicholas it was a recessive gene, for which there was no test.

Individuals with microcephaly will almost never have normal brain function. Typically, motor functions and speech are impacted and hyperactivity and mental retardation are common, although to what degree varies with each child. There is no treatment or cure for microcephaly.

The torture is this: You have a diagnosis, but no prognosis. No one could predict the severity or type of impairments that Nicholas would have. For years, we were told “don’t hope for anything”—an impossible task.

Now, in the present, I continue to hold two opposing thoughts in my mind. While I can say the words that describe Nicholas’s diagnosis, and know them to be true, I still have days where I cannot believe that this catastrophic has happened. Let me be more specific: I cannot believe that it happened to me, my husband, my family or my son. We presumed, like every parent if they are honest, that our child would be an extension of ourselves. We believed—a belief that in moments I still cling to irrationally—that Nicholas would be afforded the same opportunities that other children have.

Instead, we worry about the life that Nicholas will have. Will he be able to live independently, have a job, fall in love? Unlike with typical children, thinking ahead about Nicholas, even in small increments of time, is perilous.

When Nicholas was born, I remember wishing that I believed in God, any God. I imagine this would have provided comfort. I would have been grateful for some explanation, no matter how simplistic or fantastical.

I had several small sandalwood figurines of Ganesha, the Hindu god, that I had bought many years ago when I traveled to India with my uncle. Jon and I found ourselves placing tiny Ganeshas around our apartment. It seemed fitting, as he is known as the remover of obstacles, the lord of good fortune, and the lord of intelligence.

Somewhere I learned that it is good luck to rub Ganesha’s belly, and so we rubbed Ganesha’s belly every night before we went to sleep, thinking unspoken prayers to him. We both took a turn (two wishes are better than one). I never asked Jon what he wished for. As for me, it changed each day. I’d wish for Nicholas to roll, to sit up, to hold a cup, to point, to crawl, to walk, to say “Dada” or “Mama,” to be happy.

Christine Grounds

When I put Nicholas to sleep at night, I would hold him and bargain. “Let’s make a deal,” I’d start. “You do the best that you can, and I will too. Just get as far as you can, and Dad and I will do everything in our power to help.” The love I felt for Nicholas in those moments, standing in the dark of his room, was desperate. The emotion, so overwhelming that at times I had to choke out these words. That I loved him and he loved me made it feel more tragic.

After Nicholas’s birth, people expressed a range of feelings that I also felt: optimism (“I’m sure he will be OK”), grief (“You must not know how to go on”), mistrust (“Are the doctor’s sure?”), hope (“You never know what will happen”) and denial (“He looks fine”). And they offered well-intentioned advice: “Join a support group,” “go back to work,” “do not go back to work,” “think one day at a time,” “focus on the present,” and “think about the future—Nicholas will need you to be prepared.”

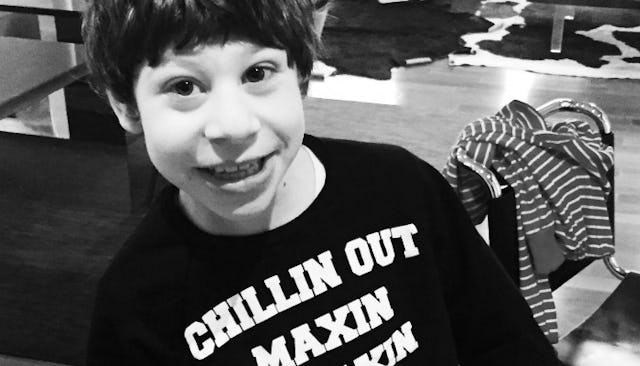

At 9 years old, Nicholas is by any standard an adorable, affectionate, curious, impish and determined child. He has been delayed in all of his milestones, but he slowly meets them. For many years, he could not communicate with words, but he was more determined than anyone I have ever known to express himself. Now he’s using four and five word sentences. This is a milestone that we simultaneously never thought possible and, still in a surreal state of denial, could never imagine him not reaching.

As gratifying as these achievements are, they are also bittersweet. Despite his gains, he will never “catch up.” He will never be able to function in the way that he or we would want for him. This makes me angry. Yes, it’s been nine years and perhaps, as some people would say, I should accept his disabilities. I believe that I will always have moments when I am aware of the contrast between my reality and my expectation of what life was supposed to be. There are numerous moments of joy, laughter, pride and contentment, but the feelings of anger, sadness and disbelief are never far away. This is my reality.