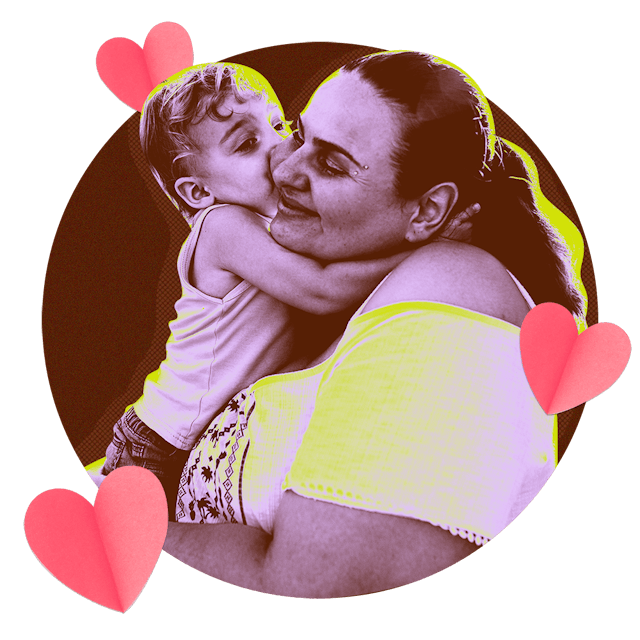

Motherhood Helped Me Love My Fat Body

After so long, I finally had a vocabulary to describe myself that didn’t hurt.

By the time we adopted our infant child, I’d done my best not to think about my physical self for almost three decades. I spent those decades regarding my body, in general, as a sort of coat stand for my brain, a mere vessel that carried the only genuinely important part of me.

This was true, oddly enough, even when I went through periods of what I now recognize as disordered eating. What I did wasn’t really about my body, and how I did it required actively disassociating myself from my body. Weight loss, for me, was always more about control and a sense of accomplishment than what pants size I might end up wearing. And extreme dieting entails ignoring your body’s frantic distress signals, its atavistic desperation for the sustenance you’re denying it.

I ignored the constant, bone-deep chill I couldn’t seem to shake. I ignored how my hair kept falling out, strand after strand. When I couldn’t stand the deprivation any longer, I also did my best to ignore how quickly I regained all the weight I lost, plus much, much more.

Mind over matter, right?

Then came our child. Then came bathtime.

Once they got too big for their little whale-shaped baby bath, I moved our nightly ritual to the main bathroom’s generous tub and climbed in with them. I sang — badly — as I washed them, and we played with little duckies and plastic mermaids and letters that clung to the porcelain walls. I formed my body into a fortress around my child, protecting them from slipping.

Courtesy HarperCollins Publishers

Over time, they grew more and more vocal. More and more observant and curious. They saw my body in the bath with them and wondered at it, pointing to the moles on my arms, the raised blue varicose veins on my right calf, the tiny red angioma on my lower thigh. They patted gently and explored the textures of those features. Features that, of course, most people would call flaws. I probably would have called them flaws too, except I couldn’t.

I disengaged with my body for many reasons, but I suspect my family legacy of fatphobia might have been the initial impetus. My beautiful mom raised me lovingly, but didn’t offer much loving kindness to herself, especially to her own, larger body. I spent my childhood listening to her denigrate herself, listening to my father denigrate her too, and it was far too easy to internalize those criticisms. From the age of six or so, I was noticeably fat, so why wouldn’t those hateful words apply to me as well? How could they not?

Better not to think about it. Better not to think about my body at all.

I refused to do the same thing to my own kid. I wanted no part in perpetuating that terrible family legacy, and the prospect of my child — my beloved, beautiful child — disassociating so completely from their body that they would willingly starve for months at a time — no. No. The thought sickened me.

When my kid looked down at their belly and legs and arms, or scrutinized themself from head to toe in the mirror, I didn’t ever want them to see flaws, but just... a body. Neutral. Neither good nor bad. Important, but not a reflection on their worth or lack thereof.

In fact, it could even be a source of joy for them. Not because it was thin or considered beautiful by others, but because it was unique and theirs.

So when they began to study my body in the bathtub, I tried to find the most loving possible way to describe myself, in hopes that love would make it easier for them to love their own body someday.

“What’s this?” they asked, pointing to one of my many moles.

“It’s a chocolate chip,” I told them, and we pretended to gulp down the chip.

“What’s this?” they asked, pointing to my varicose veins.

“It’s a blueberry river,” I told them, and we pretended to slurp up its delicious waters.

“What’s this?” they asked, pointing to my small, raised red angioma.

“It’s a strawberry,” I told them, and we pretended to eat the sweet fruit and laughed.

I’ve screwed up as a parent in hundreds of ways. Thousands. But I got that much right, thank goodness. My child has never heard me criticize my appearance, and so far, at least, they seem entirely comfortable with their own.

Funny thing, though. I was kind about my body for their sake, not mine. But if you spend enough time looking at your own body and talking about its idiosyncrasies as fun features, rather than flaws — somehow, it sinks in. It sank in.

My varicose veins weren’t ugly or embarrassing. They were a blueberry river. My stretch marks were tiger stripes, or maybe the lingering reminder of an encounter with a tiger’s claws. My round belly was soft and warm to squeeze, like a pillow.

I finally had a vocabulary to describe myself that didn’t hurt.

Then, when my child was four, I began writing contemporary romances. From the beginning, I featured fat women in my stories, and from the beginning, I thought hard about how I wanted to describe them. How I wanted their love interests to perceive them. How they would think about their own bodies.

Words have power over adults too, whether those words are coming from a partner, a parent, a stranger, or a paperback in your lap. I didn’t want to hurt anyone with what I wrote, and I didn’t want to perpetuate some other family’s legacy of pain and body-shaming.

The way I framed my body for my child became the blueprint I eventually followed in my writing. I’ve never tried to hide or elide the fatness of my characters, their dimpled thighs and silvery stretch marks and generous bellies. Instead, I’ve described those features as kindly as I described myself for my kid.

Dimples and marks and curves don’t have to be flaws. They aren’t flaws, if they aren’t deemed so. They’re simply…characteristics. Unique aspects of ourselves that can be loved, both in fiction and real life, by us, our partners, and our families.

The way I sometimes explain it in interviews is this: My fat characters aren’t desired and loved despite their bodies, or because of their bodies, but because of who they are, including their bodies.

I wrote about my characters that way for one book. Five. Ten.

You can probably guess where I’m going with this.

Turns out, writing lovingly about fat bodies did pretty much the same thing as speaking lovingly about my fat body to my child. Inevitably, all that love and kindness sank in.

If I truly considered my characters beautiful and worthy of devotion and desire—and I did; I do—how could I not extend myself the same grace? How could I not begin to see myself in the descriptions I chose to use?

I’ve never been one for affirmations. But talking about my body with respect and affection, writing about bodies like mine with respect and affection, changed me. The words I used gradually displaced so much of the fatphobic ugliness I hadn’t been able to shake, even with therapy and the love of an adoring husband. They drowned out the hateful internal monologue I’d been unwillingly repeating to myself for decades.

Thinking about my own body is easier than it used to be. Living in my own body is easier than it used to be. And it all started with a bath, a blueberry river, and a child splashing in the bubbles, curious about their mother’s body and studying it with love.

Until, eventually, she could do the same.

Olivia Dade grew up an undeniable nerd, prone to ignoring the world around her as she read any book she could find. Her favorites, though, were always, always romances. As an adult, she earned an M.A. in American history and worked in a variety of jobs that required the donning of actual pants: Colonial Williamsburg interpreter, high school teacher, academic tutor, and (of course) librarian. Now, however, she has finally achieved her lifelong goal of wearing pajamas all day as a hermit-like writer and enthusiastic hag. She currently lives outside Stockholm with her delightful family and their ever-burgeoning collection of books.