Today's Kindergartens Are Getting It Wrong

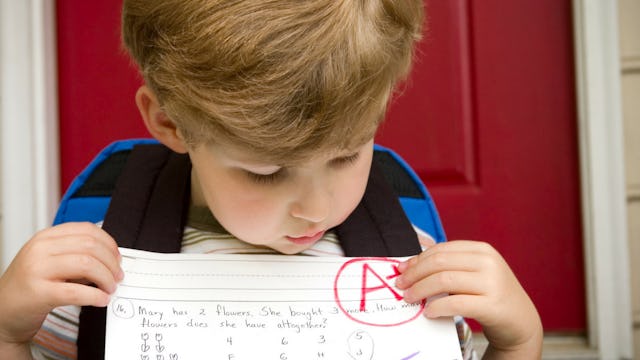

If you step into a modern kindergarten class in America, here’s what you might see: A teacher reviewing sight words with his or her students. Kids reading to one another in pairs. Students practicing addition or subtraction. Kids learning about earth or plant science. Students writing in journals. Kids and teachers engaged in state-mandated assessments.

What you probably won’t see a whole lot of? Play.

In generations past, kindergarten was where kids mainly learned how to go to school, get along with other kids, and develop impulse control. I remember my kindergarten experience involving a lot of paint, glue, crayons, and naptime—and I only went to kindergarten half day.

That was thirty-(cough) years ago. But apparently, kindergarten has changed a lot just in the past twenty years.

In a 1998 survey of kindergarten teachers, 33% said that kids should know how to read by the time they leave kindergarten. By 2010, that number was 80%. As time spent on literacy has gone up, time spent on arts, music, and child-led activities has gone down. Standardized tests have become commonplace, and full-day kindergarten is the norm.

Christopher Brown is a former kindergarten teacher and current Associate Professor Curriculum and Instruction in Early Childhood Education at University of Texas at Austin. In their research, he and his colleagues have found that kindergarten students are expected to have academic knowledge, social skills, and the ability to control themselves when they enter kindergarten—expectations that used to be the territory of first grade.

The year between kindergarten and first grade might not seem like a big difference, but every year of early childhood involves major changes in development. I know from witnessing my own kids growing up that the year between age five and age six was huge.

As part of his research, Brown interviews children, teachers, and parents about what they think kindergarten is and what they think it should be. He shows them a 23-minute film that he made about a typical day in a public school kindergarten classroom.

In the film, 22 kindergarteners are with one teacher for almost an entire school day. They do about 15 academic activities during that time, including literacy, math, and science. Recess lasts about 15 minutes and happens in the last hour of the day.

When Brown asks the teacher why she covers so much material in a day, she replies, “There’s pressure on me and the kids to perform at a higher level academically.”

This teacher is required to assess her students not only for her own instruction purposes and quarterly report cards, but for school-based reading assessments, district-based literacy and math assessments, and state-mandated literacy tests as well.

Along with that pressure and assessment comes a reduction in play time. There’s so much kids are expected to learn, there just isn’t time for them to enjoy the building stations, dress-up corners, and dollhouses of old during school hours.

But according to Brown and other child education professionals, we are throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater when we drastically reduce play and free exploration time in the classroom. That’s because young children learn naturally through play—not just academic skills like language and math, but social interaction skills like negotiation and compromise.

And in fact, taking a more sit-down-and-listen approach to learning in kindergarten can backfire, resulting in worse long-term academic outcomes and creating stressed out kids who are unenthusiastic about school and learning.

But we don’t have to go down this road. One American researcher noted that play-based Finnish kindergartens include two kinds of play: spontaneous free play, such as building dams in a stream, and guided play, such as pretending to sell ice cream cones to one another for specific amounts of money. Both kinds of play are valuable to a child’s emotional and intellectual development.

But that’s not all. Play also invokes a key element of early childhood that is rarely a focus of curriculum planning—joy. Rather than move farther away from play, as American schools seem to be doing, Finland’s curriculum is pushing their play-based approach further. And joy is a big part of that. A counselor for the Finnish Board of Education points to an old Finnish saying as inspiration for this approach: “Those things you learn without joy you will forget easily.”

Are we sucking the joy out of our kids, starting with their very first year in school? Are we creating over-stressed five-year-olds with methodology that not only doesn’t make developmental sense, but has proven to have less desireable outcomes? Would it really be so terrible to slow down a bit and let kindergarteners be kids and learn in ways that come naturally?

Considering the research on the positive relationship between play and learning, what could possibly be the down side?

This article was originally published on