This Is How Having A Son Changed Feminism For Me

The day I found out I was having a boy was not a great day in U.S. history. It was the day Trayvon Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman, was released on bail. The day we were all reminded that when it came to hatred and ignorance, no one — not even an innocent child — was exempt from being swallowed up by it.

Before that day, I identified without question as a feminist. As a woman of color, I aligned myself with the womanist principles of Alice Walker and Delores Williams. I was part of the Women’s Law Center’s campaign for equal pay in 2010. I supported, marched with, and donated to the Planned Parenthood Action Fund in New York. I worked for an organization that provided shelter to displaced and homeless women with children. I was also one of two girls in my family. We were the daughters of a single working mother who was the daughter of a single working mother. My focus was firmly planted on Venus.

And then I gave birth to a boy.

I think the first thing anyone thinks about after giving birth (aside from “shit, I hope I don’t drop it”) is the beautiful life you hope he or she will have. You think about all of the possible obstacles and trials they’ll have to overcome. You consider who they may turn out to be. Will they be strong, meek, passive, easily depressed, over-opinionated, comical, musically inclined?

You wonder if your child will be athletic or gay or allergic to peanut butter. You wonder which bones they’ll break one day and how you’ll handle it. You revisit these thoughts in moments of downtime or while in line at the bank. And after all of the wondering has subsided (momentarily), you start to wonder how the world will receive your child.

I used to imagine having a boy would be an opportunity to raise a young man to respect women, to understand how vital women are to the global equation. I thought my focus would be to make sure my son grew up to understand the beauty and magic of women so that he would be a strong man who would contribute to equality. What I didn’t realize is that boys have to be reminded of their own magic, of their rights purely to exist, and they too have to defend their right to equality. It was in facing these realities that my feminism was challenged, broken down, and ultimately redefined.

The Thing About Boy Power

This all hit me one day while I was browsing the shelves at my neighborhood Target (my happy place). My son was 3 years old, and I was looking for his first batch of “big boy underwear.” I looked through the selection and realized that there wasn’t a single option available in his size. Puzzled, I stepped back a bit. And then a bit more. And then I realized something I never noticed before: The boys’ section of Target was about a third the size of the girls’ section.

Every area of the boys’ department was ransacked, depleted, and understocked, while the girls’ section was full, every size properly represented. Rainbows abound and cartoon birds aflutter — it was a goddamn utopia. The boys’ section was small, brief, and they were always out of rain boots. It reminded me of something.

I wondered if perhaps the resistance against overbearing white men who felt entitled to make decisions about vaginas they’ve never had and babies they could never carry or give birth to was actually leaving out the rest of the men in the world. I wondered if maybe feminism had to include the miseducation of masculinity and the importance of male emotional security. After all, the real oppressor to women is not men in general, it is men who have been misguided about what it means to be real men. In the defense of women everywhere, I realized I now had to defend boys too — starting with my own.

Boys suffers from eating disorders too — 25% of anorexia and bulimia diagnoses occur in males. Boys and men are more likely to successfully commit suicide. Boys have a higher rate of dropping out of high school and college. They also have a higher rate for drug abuse and alcoholism. Somehow, my mind had normalized these facts. I shrugged them off, thinking, well, there’s more men in the world, so that makes sense. But when one of those men is represented by this small, wide-eyed, chubby-cheek-faced boy who loves singing Beatles songs and lives in my house, these things begin to feel more problematic and less acceptable.

I found myself having conversations with men I never imagined I would ever have. I asked some of my closest male friends if they had ever been sexually assaulted or raped. Out of about 10 guys only 2 said they had not. I suddenly realized that so many of the concepts of self-love, consent, personal space, physical self-ownership, and community awareness were missing or understated for men. This was especially an issue for men who were raised by single working mothers (like myself). Paying attention to the development of our sons is as vital to the health of our society as paying attention to the welfare of our daughters.

Boys Cry Too

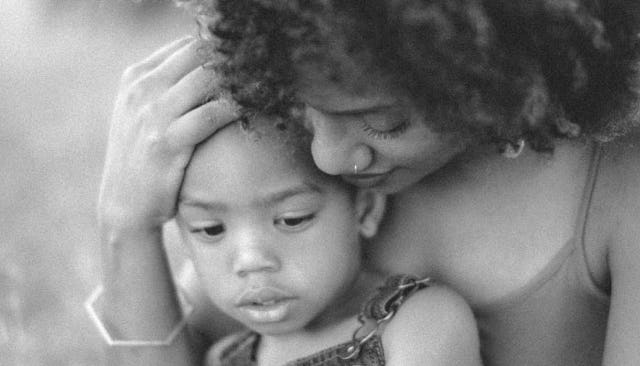

One of the most valuable lessons I learned early on when it came to my son was to allow him the space to be emotional. Every parent gets to a point where tantrums have gone on long enough, and it’s time to initiate the “Okay, reel it in” pep talk. But generally speaking, I have made a conscious effort to give him the necessary space to be sad, frustrated, and even angry.

The only time I interfere is when the emotion is displaced (that famous fit he had because I wouldn’t let him ride his bike down the stairs). What I’m hoping to teach him is that his emotions are his own responsibility. I won’t coddle them, I don’t have to affirm them, and I don’t have to agree with them in order for them to be valid. From a very young age, I encouraged him to “take a moment” — to find a quiet spot and experience his emotions within his own comfort zone and timeframe — and assured him that when he was ready to share them with me, I would be willing to listen.

I also gave my son the opportunity to create ownership over his person. If he didn’t want to hug or embrace a family member, I didn’t let anyone pressure him. If he feels uncomfortable with someone (even a teacher), I do my best to follow his cues and respect his preferences. This business of telling boys to “suck it up” is hopefully dying out, as we realize that it’s not our place to assign strength quotas to our children’s genders. My son isn’t even 5 years old yet, and I can already understand quite clearly how so many young children can properly identify the gender they associate with, be it trans or cis.

Feminism vs. Masculinism

The most impactful lesson mothering a boy has — and continues to teach me — is that I can’t be a feminist without being a masculinist. I cannot think of a single male-related feminist issue that does not hang on hypermasculinity in some way. I cannot think of a single issue we’re facing as our government shifts into conservatism that is not in someway hinged on the inability for men to empathize with women and our physical and emotional journey. Raising my son to be conscious, considerate, and to accept himself are the building blocks of a man who hopefully one day will stand on the side of what is right whether it benefits him or not.

Boys who grow up feeling confident, loved, respected, and trusted don’t need to seek hypermasculine security blankets to confirm who they are. They don’t need to harass or exert authority over women to prove their worthiness. They don’t feel threatened by a society that places value on equality and fairness. They become leaders who embrace their truest nature, and in turn, their truest strengths. This, at least, is my hope.

If we as women, as feminists, as participants in a liberal nation must uplift our daughters, then we also must uplift the men they will one day encounter. I’m starting with my son.

This article was originally published on